The Capital Beltway, commonly referred to simply as ‘The Beltway’, is a circumferential highway that encircles Washington, D.C. This article delves into its fascinating history, from its early proposals to its significance in today’s urban landscape.

Love it. Hate it. It has some of the most confusing terminology for out-of-towners. Inner loop of what? Outer loop? But there’s only one Beltway. Wait, I’m on 495, but also 95, and that’s 295? That’s not confusing.

Super GoDC reader, DrCapsFan (if we make t-shirts, he might get the first) suggested doing a little research into the Capital Beltway. This one will likely be a challenge, but I’m sure some interesting history is laying dormant. So, thanks for the suggestion and let’s get down to it.

Origins of the Capital Beltway

In 1919, the Commissioners of the District of Columbia were pushing Congress to pass a bill and consolidate the Civil War forts around the city into a “Fort Circle” system of parks. The bill failed to pass both houses of Congress.

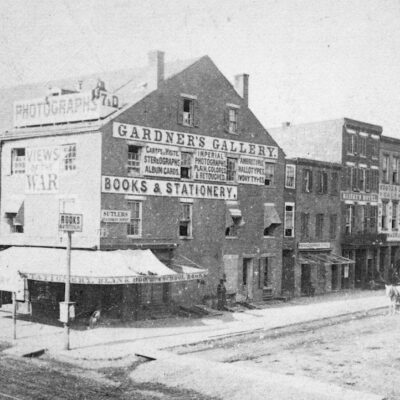

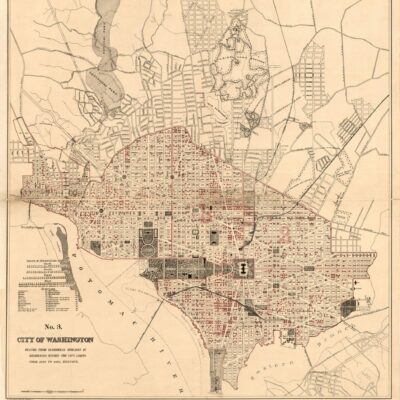

A similar bill passed in the 1925, authorizing the purchase of the now privately owned forts around the city. Land was beginning to be acquired and the first reference I find to any ring road or circumferential highway in the newspapers is in the Baltimore Sun on March 30th, 1930. A small mention of it came up in an article about the ambitious park plans of the nation’s capital.

One of the most ambitious plans for park improvement within the District is the proposed acquisition of all of the twenty-four remaining Civil War forts which circle the city … Fourteen of the twenty-four already have been bought and when funds are available to purchase the rest a parked drive will be constructed joining them all. This park drive would extend in a circle around the city, but well within the District line, and in addition to providing a pleasure route for motorists, would be a highly practical circumfierential highway counted upon to facilitate the movement of traffic along the rim of the district.

Challenges in Building the Beltway

Decades of bureaucracy, politics and World War II slowed the acquisition of the property and by the 1960s, President Kennedy was pushing Congress to seal the deal and build Fort Circle Drive. By this point, urban development in Washington had outgrown the circle of forts and surface streets had reached them. The planned road had little use at that point and the grand drive to link the forts was dropped.

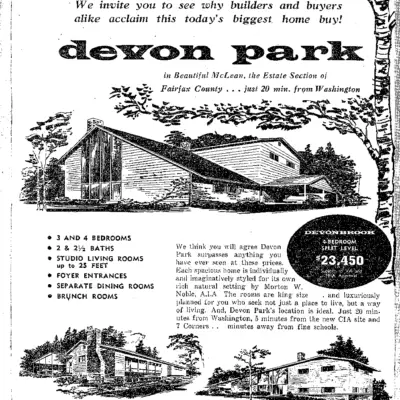

The genesis of urban circumferential highways was in the 1930s and evolved through the explosion of automobile transportation in 1950s, coinciding with Eisenhower’s push for an interstate highway system. Postwar America was hungry for their piece of the American dream, and that included a house in the suburbs and a car. America needed roads, and a lot of them.

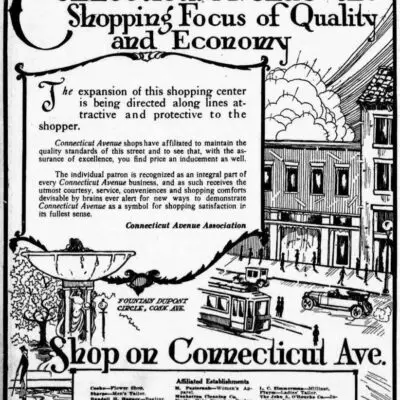

The next major mention of it in the Washington Post is March 8th, 1951. The Senate Public Works Committee was asking for a proposed road to encircle the city and the Public Roads Bureau pulled together an initial map showing where the road could be built. The road would be a limited-access, high-speed loop to facilitate the travel of dispersed government employees throughout the metropolitan area as the city population expanded into the suburbs.

A bill was proposed and debated on the Senate floor in April of 1951 with the goal of moving several Federal agencies outside of the District to Maryland and Virginia. The size of government had ballooned dramatically as a result of World War II and had outgrown the buildings in D.C. Senator Spessard L. Holland of Florida was the loudest advocate, claiming it would solve space shortages, beautify the city (by razing the temporary World War II buildings on the Mall) and reduce the attractiveness of Washington as an enemy target (wow, what foresight … and still relevant) by dispersing agencies and help solve the region’s traffic problems by building a high-speed circumferential highway in an “arc about 11 air miles from the White House zero mark.”

There was a slight sense of urgency to get started on an outer ring road as the suburbs were starting to accelerate their development. And the more development, the further out the road would have to go due to the cost of acquiring the right-of-way.

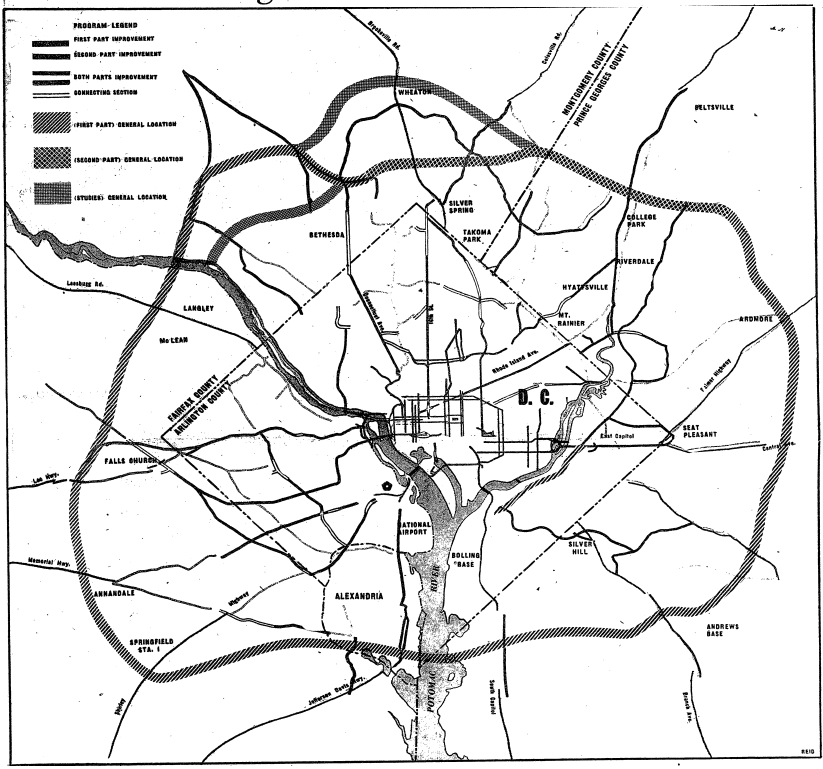

In December of 1952, the Washington Post published the recently disclosed plan of the Regional Highway Planning Committee for Metropolitan Washington. The proposal included a new four-lane ring road encircling the nation’s capital as well as significant improvements to the major thoroughfares into the District. The total price tag was whopping $328 million for this giant public works proposal.

Included in the proposal was the $26,200,000 Rock Creek Parkway. Who doesn’t love that road? It’s almost like you’re not in a city when you’re on it.

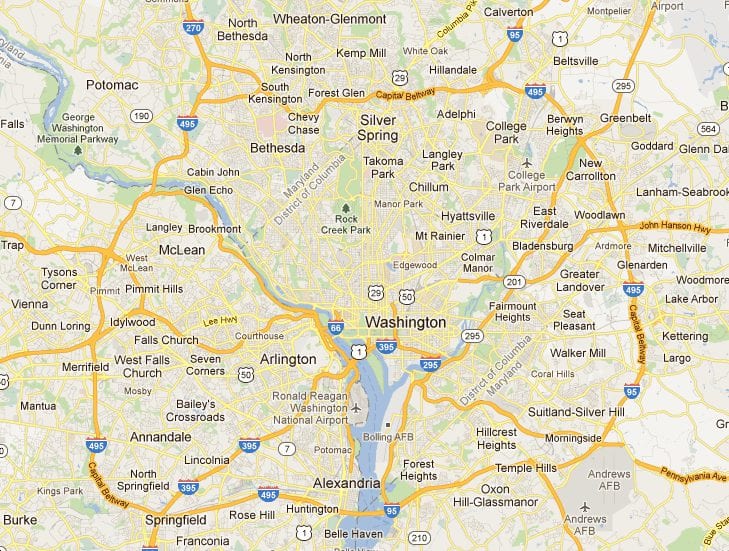

It’s a little difficult to compare, but the proposed route is a close match to the actual route below (thanks Google Maps).

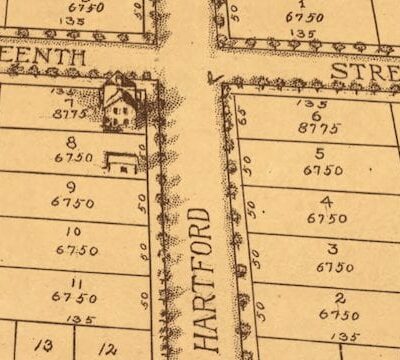

When you build a road, the goal is obviously to efficiently use tax-payer money. And to keep land costs down, the Maryland State Roads authorities attempted to route the highway through as little developed land as possible.

It was possible to stick to this plan through Prince George’s County. In Montgomery County, it was a different story. Bethesda and the surrounding areas were quite developed with affluent subdivisions and large homes. Carving a path through expensive property was not something that was financially or politically possible.

Countless properties had been acquired in Prince George’s county, but this was going to be a fight. The only way to complete the proposed highway was to cut a three-mile pass through federally owned Rock Creek Park (probably political suicide today).

As with any project on this scale, there were some major opponents … especially to that Rock Creek Park move. This was one of the most controversial decisions and a number of opponents took their grievances to court in trying to block NCPC or at least reroute the planned highway.

Labeling the opposition as anything less than vitriolic would be an understatement. Below is a letter to the editor from the Washington Post in May of that year.

Your paper tells us of the determination of the Maryland State Roads Commission to wade into Rock Creek Park with its highway program in spite of protests. So, score another point in favor of arrogant defiance by public officials in the war against law, orderly procedure and the public interest.

The Maryland State Roads authorities defied not only the thousands of friends of Rock Creek Park but the congress, the Department of the Interior, the Courts of the District and Maryland, and the law itself. “Here we go,” they seemed to say, “try and stop us.”

The residents of Parkwood Drive in Bethesda were vehemently against the Rock Creek plan and 21 neighbors unified behind a petition to halt development in the park. Mr. and Mrs. Robert Brownell were two major opponents and residents of Parkwood. They filed suit to stop development of the highway in April 1955, but they were unsuccessful in stopping development.

The alternative to the Rock Creek segment was to route the highway a mile to the north, which would have been better from a traffic engineering perspective, but as stated before, a political impossibility due to the affluent neighborhood it would have to cut through. The path of least resistance was unfortunately through Rock Creek Park.

On September 28th, 1955, the Federal Government gave the final blessing to being the city’s new “Belt Highway.” This improvement was part of Eisenhower’s push for a nation-wide 40,000-mile network of interstate highways.

The battle over this segment of the highway was one of the most contentious debates during the entire project.

Nine years after final approval, on August 17th, 1964, the full ring road was complete and dubbed the Capital Beltway (segments of the road had been opening since 1957). A number of alternate names were proposed and considered, all of which were required to easily fit on reasonably sized road signs. Proposals considered were “Colonial Beltway” and “Colonial Parkway.” The Maryland side settled on the name “Capitol Beltway” and the Virginia side agreed to the name “Capital Ring,” but state officials wanted a name that would honor favorite sons George Washington or George Mason. In the interest of uniformity, Virginia adopted “Capitol Beltway” as the official name.

But wait, that’s not the end of it. Officials and citizens were complaining that “capitol” referred only to the building housing Congress and “capital” referred to the entire city, so it would be more accurate nomenclature using the latter. On June 22nd, 1960, the highway was officially renamed the “Capital Beltway” by both Maryland and Virginia and the name has remained since then.

Imagine if you were stuck in traffic on the Colonial Beltway or the Capital Ring instead. Ya, I don’t think that would change anything. It would still be a soul-sucking experience.

From its early beginnings to its current status, the Capital Beltway remains an integral part of D.C.’s infrastructure, facilitating the movement of millions and standing as a testament to the city’s growth and evolution. If you want to read more from sources around the internet, take a look below at the links we have compiled.

- The Beltway Turns 50: Stuff You Didn’t Know About Washington’s Infamous Road

- A Brief History of the Capital Beltway

Details About the Capital Beltway

- Length:

- The Capital Beltway is approximately 64 miles (103 kilometers) in circumference.

- States It Traverses:

- The Beltway traverses two states: Virginia and Maryland, while encircling the District of Columbia.

- Major Junctions:

- The Beltway has several major junctions including:

- I-95, which merges with the Beltway for a portion in Maryland.

- I-66 in Virginia.

- I-270 in Maryland.

- US Route 50, which connects Washington, D.C. to Annapolis, Maryland.

- The George Washington Memorial Parkway in Virginia.

- The Dulles Toll Road in Virginia.

- The Beltway has several major junctions including:

- Traffic Statistics:

- The Capital Beltway is notorious for its traffic congestion. On average, certain stretches of the Beltway can see over 200,000 vehicles per day.

- It is also considered one of the most congested highways in the U.S., especially during rush hours.

- Nicknames:

- Locals often refer to the Beltway’s two main directions as the “Inner Loop” (clockwise) and the “Outer Loop” (counterclockwise).

- Trivia:

- The American Legion Memorial Bridge, which carries the Beltway across the Potomac River, is one of its busiest points.

- The Beltway is famous for the “Mixing Bowl” interchange in Springfield, Virginia, one of the most complex highway interchanges in the U.S.

- There are no tolls on the Beltway, except for the express lanes in Northern Virginia.

- Despite being designated as “I-495”, the portion that overlaps with I-95 in Maryland is co-signed as both I-495 and I-95.

- The Capital Beltway has been featured in several films and TV shows, often in scenes showcasing its infamous traffic jams.