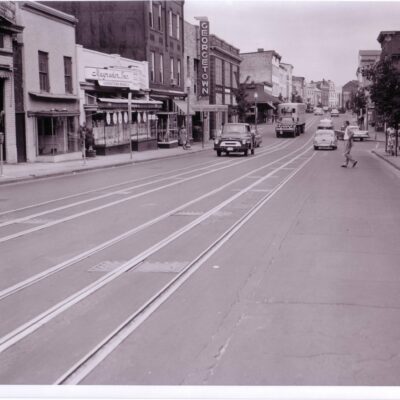

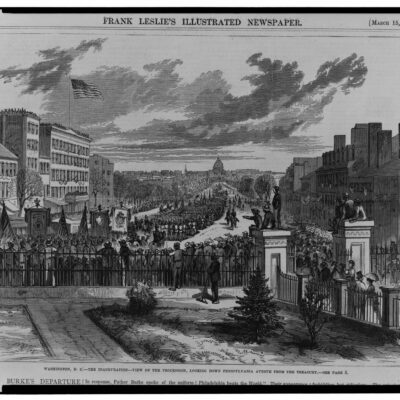

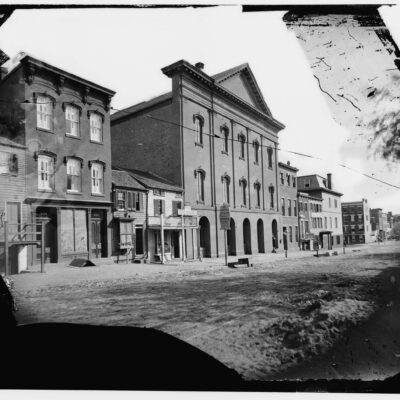

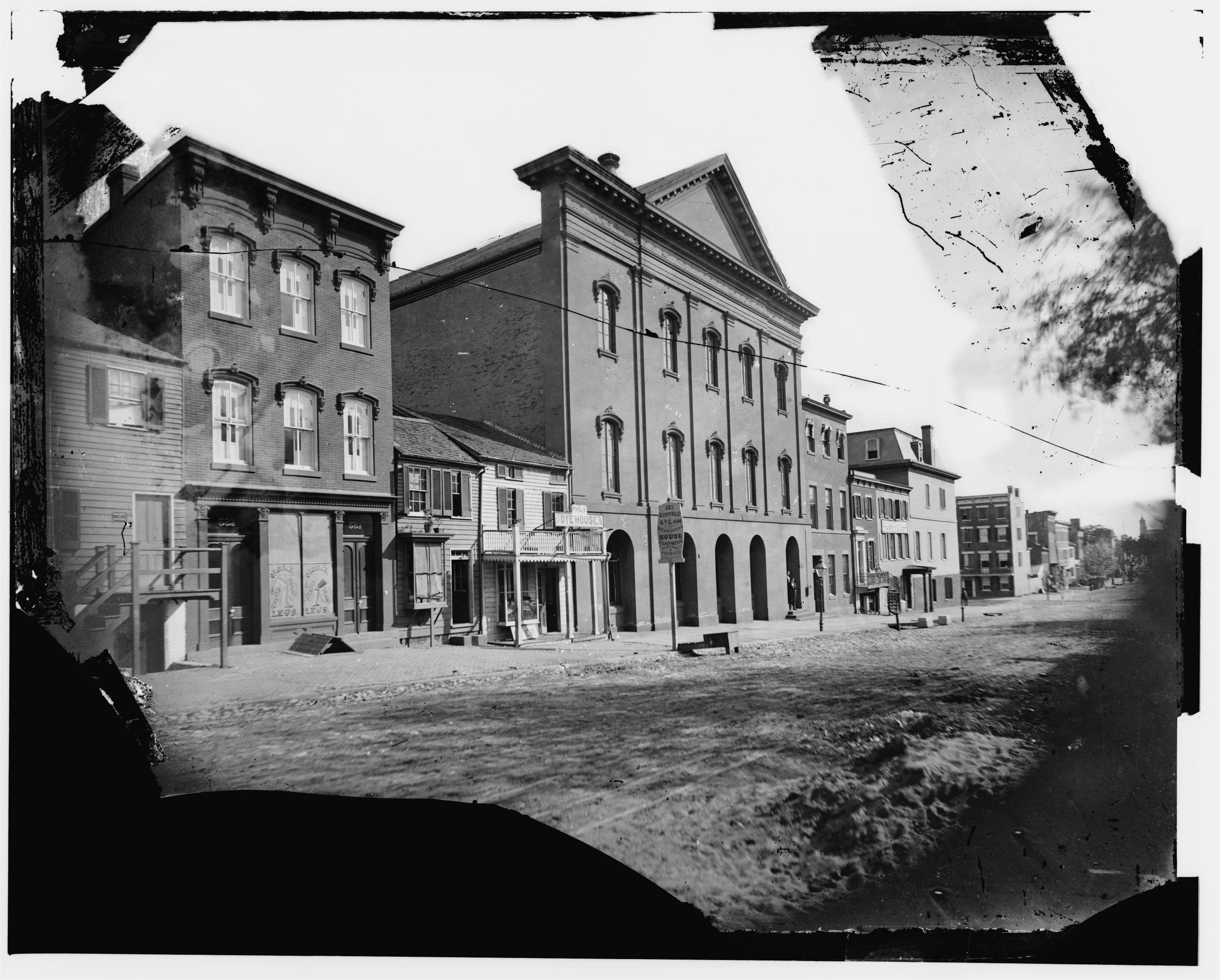

Here is a fantastic old photograph of Ford’s Theatre that we’ve probably shared previously, but this time it’s extremely high resolution. Thanks to GoDCer Konetidy for sharing this with us via email.

Because this photo is so amazing, we’re kicking off a new category of posts called “Pictures Tell a Story” and will dig up relevant information from high quality photographs. These are the photos that we can’t stop staring at or studying, and it’s about time we do some digging into the stories of the pictures.

Source: Library of Congress

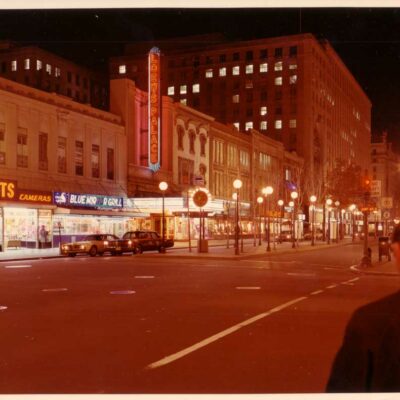

The same angle today is quite a bit different on Google Street View.

Now, for a little close-up examination of the photo. Take a look at the one below. I wonder what these guys were thinking.

Or how about this interesting photo? Either the blurry guy is being creepy, peering around the corner onto E Street, or it’s a little more benign and he was just walking around the corner when this photo was taken by Mathew Brady.

The most fascinating part of this photo for me is the store on the left at 521 10th Street. The store below was run by an Edward Kosack, originally a cabinet maker from Prussia born in 1821. Remember that this photo was taken about a decade after the Civil War, and countless wounded soldiers had come to Washington after the war. Many of those soldiers had their limbs amputated and were in need of prosthetic legs. Mr. Kosack had plenty of products to sell to his customers.

We found an interesting article in The Washington Post from October 4th, 1885 detailing Mr. Kosack’s business.

The curtain in the window of a little store on Tenth street is the vancas for a curious painting, representing a number of human legs artistically arranged. The legless passer is informed thereby that he can procure within a substitute almost equal to the support which nature had first given him.

A Post reporter opened the curtained door, and, passing through the store-room of the establishment, found himself in a small workshop which, in the twilight, seemed like the amputating-room of a hospital. Here and there through the dim light appeared human legs, taken off above or below the knee, while arranged neatly around the wall were curious shaped saws and murderous-looking augers of all sizes, besides a number of queer tools, the uses of which the beholder could only shudderingly guess.

In a few moments a stout, middle-aged man appeared. He spoke with a strong foreign accent, and his eyes and mouth, which lighted with a smile when particularly pleased, were those of an artist. This was Mr. Edward Kosack, the proprietor.

He lit the lamp, which revealed to his visitor legs of every description hung upon nails and strewn on the floor about him. There were wooden legs, iron legs, wire legs, nickel legs and leather legs; men’s, women’s and children’s legs; legs in the rough and raw material; old worn-out legs, which revealed their ghastly mechanism. and brand new legs, which looked so natural that you expected them each moment to get up and walk off.

“I suppose most of your customers have lost their legs in the war?” queried the reporter, as he accepted the proffered chair.

“Oh, no,” answered Mr. Kosack: “railroads and machinery have caused the loss of many more legs than the war. The fact that formerly an establishment like mine was only found in the large cities, while now most every town has its leg shop, is sufficient proof that our business has been greatly helped by the railroads.”

“What is the best material for an artificial leg?”

“I use wood altogether and consider it superior to any of the various substances which have been tried. Metallic legs are too heavy, and they are conductors of heat and cold, and leather, when subjected to friction makes the encased limb unbearably warm.”

“How about cork?”

“A cork leg is something I never saw, sir,” the expert answered with a smile. “Cork is used generally in France, I believe, for the bottom of the foot, and it could be used in filling the leg, but it would be impossible to make a leg of solid cork, because its texture is such that it would not hold the bolts and screws for the joints.” Here the speaker picked up a leg and exhibited the joints at the knee, ankle and toes, which seemed almost as perfect as in a natural leg.

…

“How much does a leg cost?”

“From $75 up. As good and serviceable a leg as a man need wear can be made for $75, but of course more comfort and better finish can be had at a greater cost.”

“How long will a leg last?”

“A good leg will last you five to ten years”–this in the indifferent, calculating tone of the Gravedigger in “Hamlet.” “Now, there is a man,” pointing to a leg hanging on the wall, “who will wear his leg ten years. The Government fixes the time at five years, as it allows its maimed soldiers a leg or an arm every five years or, if not needed, commutation for same at the rate of $75 for a leg and $50 for an arm. Some soldiers will wear a leg more than five years and some a good deal less. But if a man keeps sober and decently clean he will not need a new leg inside of eight or ten years. A wooden leg, however, must be kept clean and cleanly clothed as well as any other. The old style leg had to be oiled twice a week, and if not done by a mechanic the oil was apt to run up in the wood and loosen the bolts in the joints, but the leg I make now, which is after Jewett’s model with some improvements, requires oiling only twice a year. A colored woman here in town has worn a leg a long time. She came here in 1867, when I was a new hand working for the former firm and had not been allowed to try my hand at fitting a leg. The two men who were doing that work for the firm refused to fit the colored woman’s leg, and I asked permission to be allowed to do it, which was granted. I was successful, and I often see the woman now wearing that same leg.”

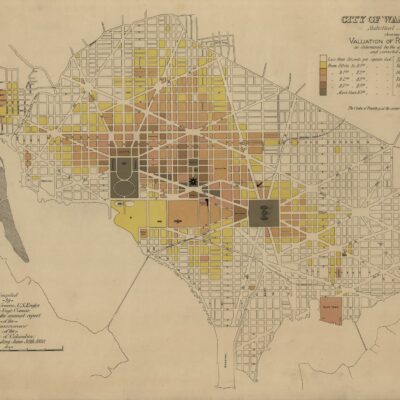

On March 15th, 1914 the Washington Post printed an article about Kosack purchasing the building at 519 10th St., next to his store. At the time, it was listed as the narrowest business structure known as the Tower building. A. E. McQueen sold the 10 foot wide building for $15,000.

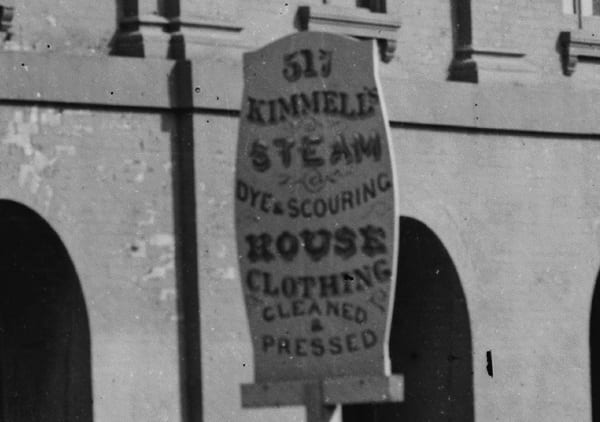

Unfortunately, we weren’t able to dig up anything on the laundry store at 517 10th St. Below is the sign in front of it.

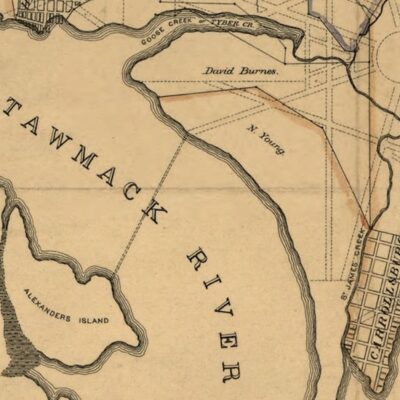

And last, you’ll notice a couple buildings south of Ford’s Theatre is Central Dispensary.

According to an article in The Washington Post on October 22nd, 1933, Central Dispensary was conceived in 1871 to give the city’s indigent sick access to general medical attention at little or no cost. Georgetown College donated use of two rooms in its building at 10th and E (pictured above). By May 1872, 511 patients had been treated with a total operating budget of $428. Four years later, in 1876, larger accommodations were required and they moved to 514 6th St. NW.

Click on the first photo at the top yourself to see what you can find.