The next “Three Things…” post will be about one of the most iconic monument in our city: The Washington Monument.

Since the cornerstone was laid on July 4th, 1848 (check out a photo of it under construction), the Monument has seen it’s fair share of history; there isn’t a shortage of events to choose from, but selecting three that you aren’t aware of will be a challenge.

I’ll forewarn you … two of these are worthy posts for “From the Crazy Vault.”

1. Woman hurls herself 470 feet down the elevator shaft

This is not a pleasant story. Naturally, given the massive height of the structure, there comes a time when someone decides to jump and end their life.

The Monument made it about 30 years after it’s official opening before the first suicide. Mrs. Mae Cockrell of Covington, Kentucky threw herself down the elevator shaft on February 23rd, 1915.

Mr. and Mrs. Cockrell had arrived a week prior to visit some relatives in the area and see a specialist about Mrs. Cockrell’s ill health. She suffered from insomnia and “nervousness,” which likely was anxiety or severe depression. She was despondent when the doctor was unable to give her any recommendations to help her and felt she was doomed to a depressed existence.

Earlier in the 20th century, reports of death were far more graphic, so I’ll spare you the morbid details. But, the story details her ascent in the elevator with the rest of a tour group. Two Walter Reed Army Hospital nurses were standing near the top landing when Mae headed down a flight of steps to start scaling the grate covering the elevator shaft.

The nurses were unsuccessful at preventing the climb and watched in horror as Mrs. Cockrell paused at the edge for a few seconds before throwing herself down the shaft.

Here’s a brief excerpt from the article:

Ill health is given as the cause for the act. Mrs. Cockrell left a note to Dr. Thomas A. Williams, of Washington, saying she could never get well. Another note written on a prescription blank was found addressed to her husband, in case of Mrs. J. Gary, Del Ray, Va., which read as follows:

Forgive me, sweetheart, but this is my only way out. Always remember I love you and you are the dearest husband in the world. Please burn my body.

A sad, sad story about a woman who saw no way out.

Positive side note: 11 days earlier, on the far end of the Mall, the cornerstone was laid in what would become the Lincoln Memorial.

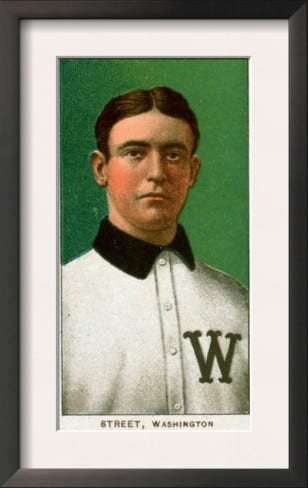

2. Senators’ Gabby Street, the first to catch a baseball dropped from the Monument

Old Gabby was not the best baseball player. He appeared in parts of eight seasons as a catcher in the Major Leagues for the Cincinnati Reds, Boston Braves, New York Highlanders (i.e., the Yankees), St. Louis Cardinals and our hometown Senators.

To his credit, he did have two major accomplishments to be proud of. The first was being the primary catcher and mentor to a young Walter Johnson, greatest pitcher in Washington history and quite possibly all of baseball. The second was being part of a publicity stunt to catch a baseball dropped from the top of the Washington Monument.

In August of 1908, journalist Preston Gibson stood at the top of the Monument and dropped a baseball. It plummeted over 500 feet to the ground where Gabby was standing in street clothes and a catcher’s mitt.

The ball hit the heel of his mitt and bounced out. Twelve more tries and he finally caught the ball, winning a $500 bet as the first person to catch a ball thrown from the top of the monument.

Street confided many years later that he was disappointed he didn’t catch the first one.

Actually, I should have caught the first ball they threw out … Had my mitt on it and dropped it, when I should have held it. I knew then that it could be done, but the winds bothered me until I finally snagged the thirteenth toss.”

He finished 1908 as the Senators’ catcher and played three more seasons in Washington before Clark Griffith sold him to New York prior to the 1912 season.

3. Sniper shoots and kills purported bomber

That’s right, back on December 8th, 1982, Norman D. Mayer, a 66-year-old Navy veteran, drove his white van to the entrance at the base of the Washington Monument (some of you might remember this).

He exited the vehicle wearing a black motorcycle helmet, a blue snowsuit, carrying a remote control and threatened to destroy the Monument with 1,000 pounds of explosives loaded in his truck.

Mayer was vehemently against nuclear weapons and attempting to bring national attention to his cause, banning the weapons. He had moved to Washington that June to better directly protest the government. Frustrated by his ineffectiveness, he chose this dramatic method to garner attention to his cause.

Eight people were trapped inside the Monument but were eventually released after successful negotiations with Mayer.

Mayer held scores of lawmen at bay through the day, pacing around the monument and threatening to detonate explosives in the truck he had pulled up to the base of the monument shortly after 9 a.m. Police evacuated nearby buildings and closed all streets in a several-block area around the Mall. Mayer refused to negotiate with any law enforcement official, police said, but insisted on dealing with a reporter.

In give meetings with Associated Press reporter Steve Komarow, Mayer issued rambling demands for a “national dialogue” to prevent nuclear annihilation, a warning that politicians were “genocidalists,” a call for a ban on nuclear weapons and an instruction that the media concentrate on this issue. Mayer warned police to stay away. Komarow said, cautioning at one point: “If anybody gets cute, tries to play games, they’ll have a pile of rock.”

The entire standoff lasted 10 hours until Mayer entered his vehicle and attempted to drive away and wreak havoc on the rest of the city. Police snipers, positioned on top of the Department of Commerce building, opened fire on the van, killing Mayer and ending the ordeal that evening.

A subsequent search of the vehicle found no explosives nor weapons. Mayer was interred at Arlington National Cemetery before Christmas, 1982.

As a side note, I read a few of sources that stated this was the longest recorded police sniper killing in U.S. history at about 480 yards. And also, it is the earliest recorded use of night vision scopes by police snipers.