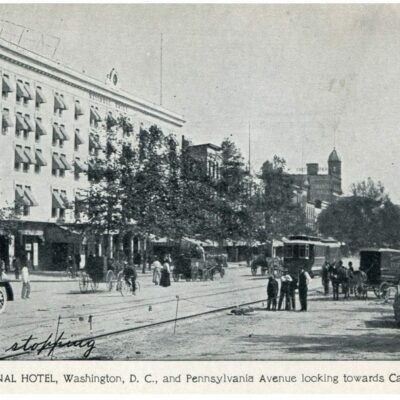

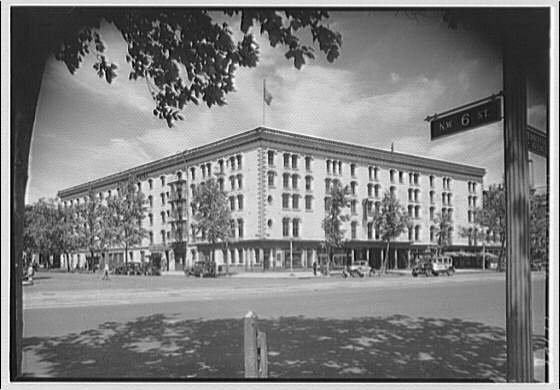

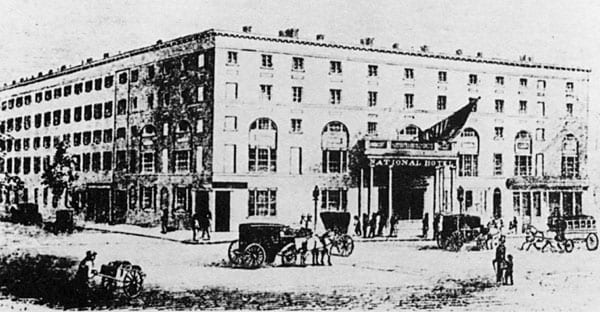

In keeping with the hotel theme this week, we wanted to share a little bit about the National Hotel, formerly situated at 6th and Pennsylvania Ave., across from where the Indian Queen was. The location is currently the site of the Newseum (one of our best museums if you haven’t yet been there).

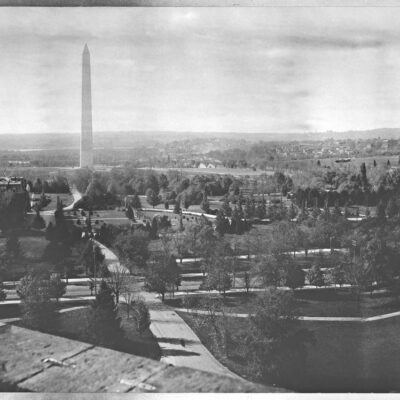

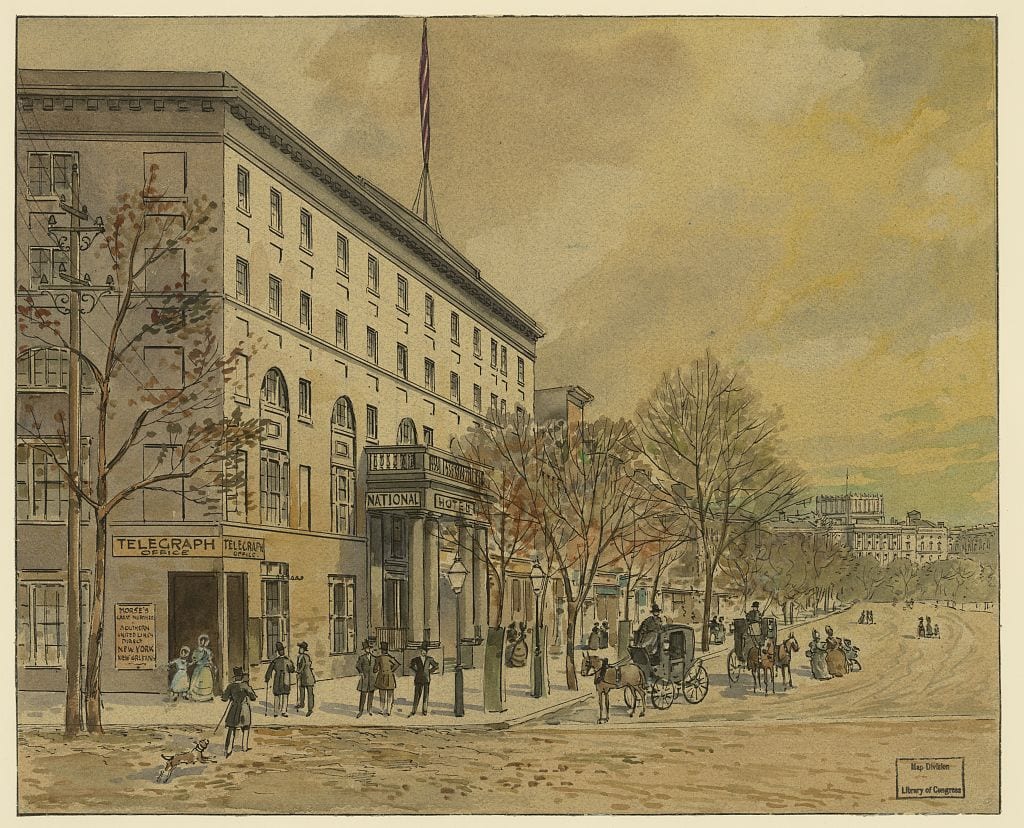

Source: Library of Congress

One of the most famous hotels in the city’s history, the National Hotel was opened by John Gadsby from Alexandria. It ceased serving as a hotel in 1931, functioning as a government building until 1942, when it was razed.

We dug up an interesting historic perspective of the hotel in The Washington Post from January 5th, 1930.

A tragedy soon will be enacted in this city the like of which Washington has seldom, if ever, seen before. The famous old National Hotel is to be razed. It is one of the oldest hostelries in America, having been in continuous operation since 1827, when John Gadsby came from Alexandria to open it. One family, the Calvert family, kin by blood to Lord Baltimore, who founded Maryland, has owned it from the beginning, and a member of that family, the other day, sold it to the Government for $580,000. It comes down now in response to the spirit of progress, to make room for the new civic center which the District government will build on the north side of the Avenue.

Apart from the Capitol and the White House, there is no building in the city so historic as this. For more than half a century the history of the Nation was made there. Within its walls great political contests that affected the destiny of the Nation were mapped out, and here the most infamous crime in American history, the assassination of Lincoln, was planned. Every President from Jackson to Lincoln was a guest there, and there lived Henry Clay; there he died.

Its cuisine was world renowned as far back as Old Hickory’s day, and beginning with his famous private dinner to John C. Calhoun and ending with the banquet given to Lincoln the day after his first inauguration by the New York delegation in Congress, its banquet halls rung with the eloquence of Clay and Webster, Calhoun and Hayne, Crittenden and Alexander H. Stephens. Chief Justice Taney, when he entertained with an official dinner, gave it at the National, for in his day it was noted for its terrapin dinners and for its rare old wines.

…

John Gadsby, the first proprietor of the National, was a noted man in George Washington’s day, for the master of Mount Vernon often stopped at Gadsby’s Tavern in Alexandria and had a bird and a bottle with the genial host. When business fell off in Alexandria, due to its proximity to Washington, Gadsby came over the river in 1827 and picked out the very site on which the National is built, and had an English architect design the building and superintend the construction. The Calvert family owned the ground and gave him a long lease on it. When completed, it was named Gadsby’s Hotel, and it bore that name until 1844, when John Gadsby sold out and retired from the hotel business.

…

Gadsby’s first guests of any note was Andrew Jackson, who went there on the occasion of his coming to Washington to be inaugurated President. Parton says that Old Hickory stopped at the Indian Queen, but Parton was not particularly noted for accuracy. He was plethoric and voluminous in his writings, but accurate never. Wilhemina Bogardus Bryan, who is one of the most careful of annalists, says it was the National, and so do other historians. So at the National Andy stays.

…

On the day of his inauguration the most disgraceful scene in history of such events took place at the White House, and Jackson, on being rescued by the company of strong men, who locked their arms about him, was glad to retire by a side door in safety to his rooms at gadsby’s. That night he sat down in a room to dinner with John C. Calhoun as his guest. The piece de resistance was a roast cut from a quarter of beer sent Jackson by an admirer. He did not fail, before retiring, to write a letter of thanks to the kind donor. What would we not give to know what he and Calhoun talked about at that dinner. Soon they would be at each other’s throats, in the bitterest of all our political feuds.

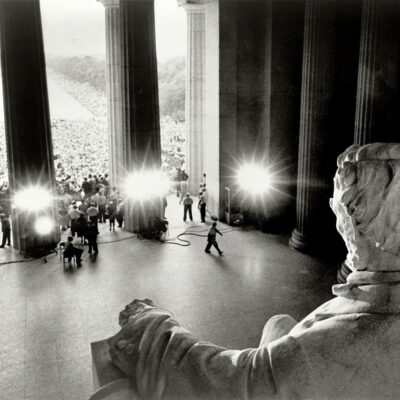

Below is a print of the hotel just before the Civil War. The view is down Pennsylvania Ave. from 6th St., and in the background, you can see the unfinished Capitol dome.

Source: Library of Congress

Gadsby ended up selling the property to the Willards (i.e., the family that had the eponymous D.C. hotel). The story continues.

Business grew so rapidly under Mr. Willard’s management that in 1852 the hotel had to be enlarged, more than a hundred guests weekly being turned away during the rush season. Mr. Calvert spent $45,000 on this, $19,000 remodeling the old building, and $26,000 making the additions, which increased the number of rooms to 356. “Of these there are three extra large rooms, capable of containing messes of a dozen each, so that the National Hotel, during the next session of Congress, will be enabled easily to accommodate 400 guests.” In 1865 it accommodated 1,100.

…

President Polk had stopped here with his lovely wife while waiting for his inauguration in 1845, and George M. Dallas, the Vice President, also. While a guest in this house Dallas was challenged to fight a duel, and accepted, but Polk used his kind offices to prevent it, and Dallas lived to be minister to Great Britain and to Russia.

…

Henry Clay died in the National Hotel just before the enlargement took place. He left his home in Ashland on November 1, 1849, accompanied only by his valet, a free man of color. Zachary Taylor was on the throne, and Clay accepted but held only formal relations with the last of the Whig Presidents. He took a parlor and bedroom at the National, and attended the sessions of the Senate but irregularly. One important speech he made before returning home.

Although his health was sensibly declining, Clay came on to Washington in December, 1851, for the last session of Congress he was ever to attend, taking his old suite, No. 32, in the National. It was as famous in his day as the “Amen Corner” in the Fifth Avenue in Tom Platt’s day, or Room No. 5, Andrew Johnson’s suite, in the old Maxwell House in Nashville.

Clay died on June 29th, 1852 in the National Hotel with his son Thomas at his side.

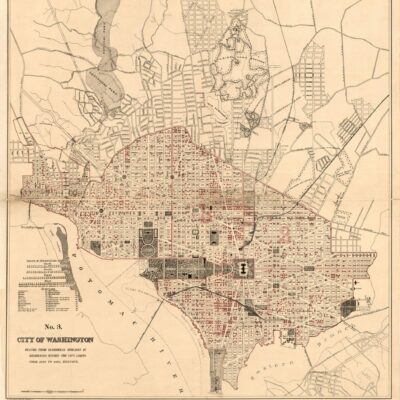

Source: Library of Congress

The piece continues with a crazy story about President Buchanan and the ominous sounding National Hotel Disease (which actually has a Wikipedia page).

When James Buchanan came on to his inauguration in 1857 he stopped at the National for several days, and on the night before the inauguration sewer gas backed up into the hotel, making all of the guests very sick, some of them desperately so. A medical officer of the Navy is accredited with saving Buchanan’s life. In the history of the city this incident is known as the National Hotel sickness, and for a long time it was believe that it came from bad food or from poison placed in the food.

…

During the secession war Gen. Ben Butler made the National Hotel his whenever he was in Washington, and here, too, lived John Wilkes Booth, “convivial in his habits, sprightly and genial in conversation.” He made many friends among the young men of his own age,” saysBen Perley Poor in his reminiscences, and he was a favorite among the ladies at the National.”

His room, No. 228, was much visited during the month of April, in which Lincoln was assassinated, and that great crime, it is believed, was hatched under the roof of that hotel. Azerodt and Herold were known to have visited him there and possibly others of the conspirators.

Booth evidently arrived at the hotel on Wednesday, November 9th, 1864 staying for two nights. He returned on the 14th for another couple of nights and while staying in the hotel, roomed with another actor, and friend, John McCullough. His friend also befell a tragic end, when he was murder by a fellow actor at the National Theatre and buried in a cellar beneath the stage. Of course, there were consistent stories of John haunting the theater thereafter.

Booth also had a few other roommates while staying at the hotel, including John P. Wentworth from California, and a Mr. McArdle. His last day at the hotel was April 8th, 1865.

Source: Gettysburg Daily