Buzzard’s Roost, Ryder’s Castle, Zig-Zag Alley, and the Barracks are all old neighborhoods which were shanties of dirt and filth. We wrote about the rough-and-tumble lost neighborhood of Murder Bay, and the equally squalid Hell’s Bottom a while back.

We came across an old article from December 12th, 1893 in The Washington Post, detailing the bleak environment of these late 19th-century Washington neighborhoods. The descriptions are vivid and bring to life what it was like back then. Remember that 1893 was the worst economic depression the United States had seen until the Great Depression. The Panic of 1893, fed largely by over-building the railroads, weak and shaky financing practices, the collapse of several banks, and a run on gold sent the economy down a deep hole.

According to the article, one in ten Washingtonians lived in abject poverty. Below are excerpts from the piece.

“How much rent do you pay for this house?”

“Two dollars and a half a month, sir; and I’m three months behind now.”

The house consisted of two frame rooms from which just about two-thirds of the plaster had fallen off in irregular areas. The moon could be seen through the cracks in the roof, and the wind blew through it like a corn crib, in spite of the fact that there was a red-hot broken-down coal stove in one corner and a smoking oil lamp without a chimney that made the air of the place unfit for cattle to breathe, to say nothing of people. This was one of the conditions, and not a theory that will confront the people who have to administer the charity of the city to the needy this winter. The house was typical, and there are certainly hundreds, perhaps thousands, as bad or worse, whose inmates will have to be cared for by the public before the hard season is over.

-ad 197-Few of the people of Washington, aside from the police force, know the extent of the poverty-stricken area in the city. There are, in fact, large sections where it is not safe for a philanthropist to go. A Post reporter, however, under the guidance of the officers of the various precincts who were familiar with the poverty-stricken districts, lately made a tour of the squalid sections of the city.

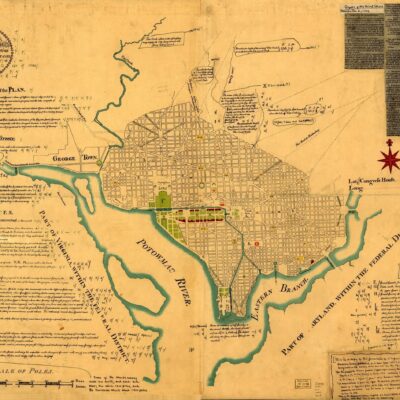

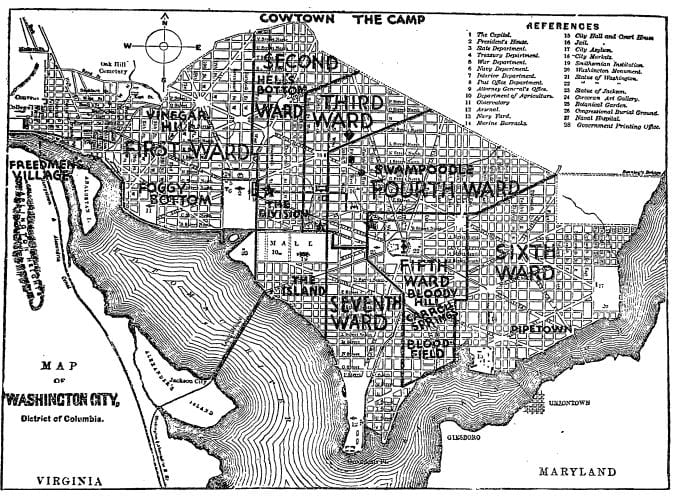

The poor districts of the city are larger than one unfamiliar with the subject is likely to suppose and the character of the poverty is worse than one can imagine who has not been through the dog-kennel houses, where six families live in a four-room house; where one’s feet sink through the holes in the rotten floors, and where the smoke-covered walls are so thick with vermin that the investigator hesitates to return to the bosom of his family without first submitting to the kind offices of the Turkish bath attendant. The worst of the poverty of the city is not in the closely settled central portions, as is shown by the fact that during the past winter from the First precinct police station, on Twelfth street, near Pennsylvania avenue, there were given out only 139 orders for fuel, coal, and clothing, against 1,400 and 1,200 from the Fifth and Eighth precincts, lying on the edges of town. The notorious Buzzard’s Roost, near Ninth and E streets, and Ryder’s Castle, another tenement of the same sort near the Baltimore and Ohio depot, and some of the narrow alleys–Temperance alley, near Tenth and D streets; Swinghammer alley, near Fourteenth and Ohio avenue, and Italian Row, back of the new Emergency Hospital–are among the chief haunts of the central city poor, but these are in the midst of well-to-do regions and not likely to suffer from neglect, as their residents are mostly of the chronic poor variety, who know all the regular charitable agencies in the city and go from one to the other as soon as the cold weather sets in, making a better living in many cases than those who have to work for it.

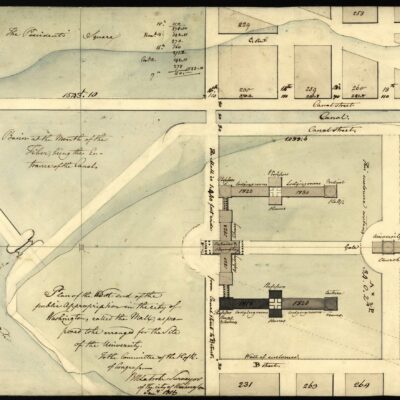

Source: The Location

Swinghammer Alley! What an incredible name. I wonder how that name came to be. The article goes on by discussing nasty areas of Southwest called Fighting Alley, Cow Town, Slop Bucket Row, Vinegar Row, and the Gut. All of these are far more creative names than what we are used to today. The piece continues …

One of the typical cases picked up at random by The Post representative in his investigation of this region was that of two empty houses on G street, between Third and Four-and-a-half streets southwest. The houses were shut up on the front and bore “For Rent” cards, but five colored women had forced entrance to the hovels from the rear and were camping out in the bare rooms. Some brush wood had been obtained–it would be difficult to say how–and served as a bed for them as well as for fuel. A tiny fire glowed in the elbow of a couple of joints of old stove pipe stuck out of the rear window. There was absolutely no furniture and no bedding, except the dirty rags that the women had wrapped around them. A few bits of broken bread and meat that they had begged on the street before going into quarters for the night was their entire supply of food.

-ad 199-…

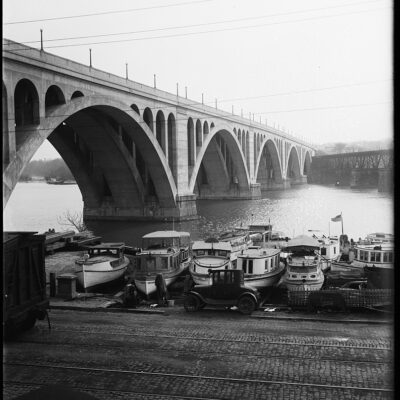

In Zig-zag alley, one of the typical houses was a single room structure, the walls black with smoke and hung with draperies of rags to keep out the wind, while the floor was full of holes reaching through to the damp ground beneath. The inhabitants were an old colored man, bent nearly double with rheumatism, and his wife, almost as feeble, whom he said was his sole support. He had made a living for himself through the fall by shoveling coal on the wharves, but was no longer able to work, and the little his wife could make, by begging and picking rags on the dump, was all they had to depend upon. An ash bedraggled cat was purring contently underneath the half cold stove, and a small “yaller” dog made his bed in the midst of the scanty woodpile in one corner.

…

The average rental of these hovels was $3 per month, payable on installments of from 50 to 75 cents per week. The owners of the most of the property were neighboring saloon-keepers, who had got possession of the dens through foreclosed mortgages. But the owners of some of the property were well-known men, whose names, if publishing, would probably have the effect of wiping out a number of these pest holes. The police who know the nature of these shiftless citizens, say that although they seldom have $5 saved ahead, the lack of employment during the past summer will make their condition through the winter much worse than if they had had employment during the preceding half year. The reason of this is that they usually live through the winter on credit acquired from having paid up their back bills with the money earned in summer. But slack work at the brick yards during the past season has already brought their credit down to the lowest edge. Storekeepers and the wood yards will no longer carry them, and they will have to live on charity for the rest of the season.

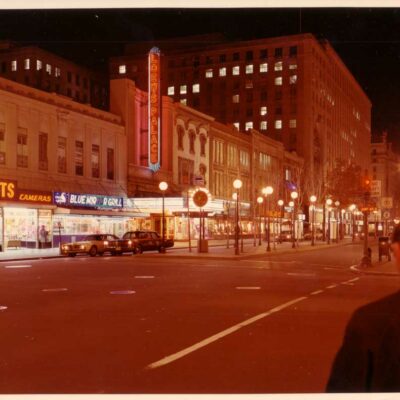

It’s sad and tragic to read about the horrific conditions of poverty across the city in the late 19th century. There are some terrific posts out there about old D.C. neighborhoods, like this one on Greater Greater Washington by our friend Kim Bender (and the original one on her blog, The Location). By the way, she works at the Heurich House Museum, which you really need to visit.