Ever driven past the Kennedy Center, headed up Rock Creek Parkway, and caught a glimpse of some odd-looking stone arches nestled between freeway ramps? If you’ve ever muttered “what the heck are those?” as you zipped by—you’re in good company. Those are the Godey Lime Kilns, and they’re among the last surviving remnants of Washington’s gritty industrial past.

Tucked just where Foggy Bottom fades into Georgetown, these kilns once churned out the lime that held 19th-century D.C. together—literally. Mortar? Plaster? Whitewash? That was Godey’s game. Let’s rewind to a time when Washington was less politics and more pickaxes.

Burnt Lime and Bureaucracy: The Early Days of Foggy Bottom’s Kilns

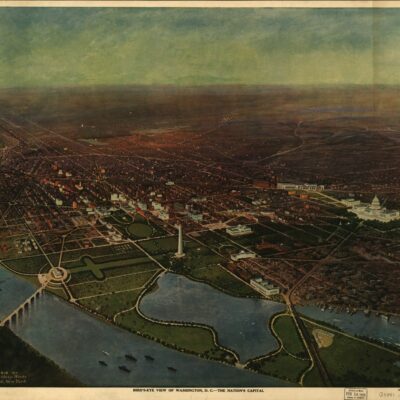

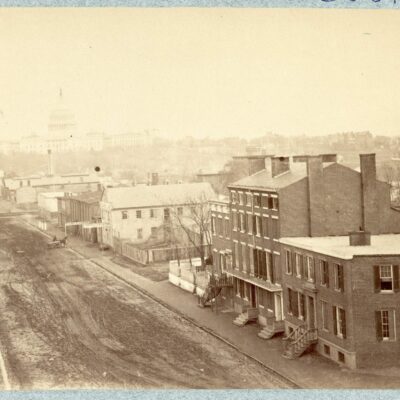

Washington wasn’t always the marble metropolis we know today. Back in the early 1800s, the city needed lime to build anything—houses, roads, even the Capitol itself. Lime comes from burning limestone, which sounds straightforward until you remember it smells like someone set a rock on fire in your living room. In 1819, D.C. tried to ban lime kilns unless you had a license. The twist? They didn’t actually issue any licenses. Classic.

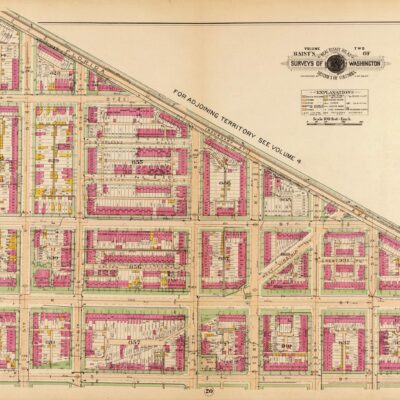

By the 1830s, the need for lime was undeniable. Enter William Easby and Joseph L. Kuhn, who built some of the first official kilns at what’s now 27th and K Streets NW. Easby, a British-born Navy Yard shipbuilder, knew a prime industrial spot when he saw one. Right on the C&O Canal and close to raw materials, these kilns were the backbone of early Washington construction.

An October 17, 1937 article in the Evening Star, written by historian John Clagett Proctor, notes that lime-making along Rock Creek dates back to at least 1833. It even credits Samuel Smoot as one of the earliest lime burners in the area, operating kilns on 27th Street before Godey ever entered the scene. According to Sessford’s Annals (cited in that article), kilns were being built on a “large and permanent scale” that year to process stone from the C&O Canal.

Back then, Foggy Bottom was a patchwork of industry—brickyards, breweries, and kilns puffing away. The kilns near Rock Creek became especially important. With limestone floated down from Seneca and Harpers Ferry, the area was D.C.’s dusty, smelly answer to the Home Depot.

Enter Godey: Washington’s Lime King

Then came William H. Godey, the man whose name would stick to those stone kilns like mortar on brick. By the 1850s, he took over the operation and went full throttle. Godey wasn’t just making lime; he was branding it. In 1856, Evening Star ads screamed “LIME!! LIME!! LIME!!” like a 19th-century hype man. He even added a private wharf for easy canal access.

The 1937 Evening Star article also confirms that Godey’s lime business officially launched in 1854, contradicting some earlier accounts that suggested 1845. His kilns covered an impressive footprint—500 feet along both 27th and L Streets—and by the 1880s, were pumping out 3,000 barrels of lime weekly.

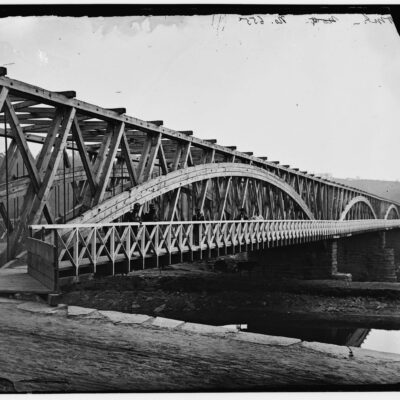

In 1864, while the country was still at war, Godey invested $2,500 (serious cash back then) to build new, massive stone kilns—the very ones you can still spot today. They were 24 feet tall, 10 feet wide, and ran hot. Like, burn-rocks-into-powder hot. Workers would load limestone in the top, stoke the fires below, and days later, rake out steaming hot quicklime.

This wasn’t boutique artisan lime—it was industrial scale. From war-time expansion to the Gilded Age building boom, Godey lime held D.C. together. Capitol dome? Maybe. Georgetown rowhouse? Definitely. Those four kilns were mini-factories fueling the city’s skyline.

A City Built on Lime (and Sweat)

By the late 1800s, Godey’s operation was one of the last of its kind. At peak production, the kilns ran nonstop. Limestone came by canal boat, got crushed, roasted, cooled, bagged, and sent out for plastering and mortaring the capital together. About 25 men worked the site, shoveling rocks and stoking fires. It was grueling, filthy work, but it paid.

Foggy Bottom wasn’t a glam zip code back then. It was smoke, soot, and sweat. Besides Godey’s kilns, there were at least five other lime operations nearby. But Godey had the primo location, and he wasn’t shy about marketing. It paid off—he built a lime empire from that riverside spot.

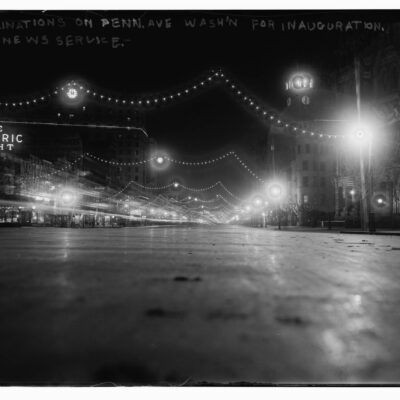

Trouble in the Air: Smoke, Complaints & Crackdowns

Let’s be real—burning limestone doesn’t smell like roses. It stinks. And by the late 1800s, Washingtonians were less than thrilled with the noxious clouds wafting from the kilns. In 1899, Congress passed a new Smoke Law for D.C. and began cracking down on industrial polluters.

Guess who was top of the list? Yep. The Godey kilns.

John McLaughlin Dodson, who took over the kilns in the 1890s, was not amused. He called the law “cruel and unjust” and took it to court. Didn’t help. In 1905, he was fined $20 for violations (more annoying than ruinous), but it was clear the city’s tolerance for smoky relics was over.

The Last Firing: Godey Kilns Close for Good

William Godey died in 1873, but his family kept the lime fire burning. His wife Mary ran the business, and later their son Edward tried to modernize. By 1884, Edward was advertising “wood-burnt lime, cement, plaster, and hair,” according to the same Evening Star article.

But the tides were turning. By the early 1900s, Dodson took over full-time. He pushed on, battling regulations and dwindling demand. By 1906, he was trying to sell the whole thing off. Classified ads offered the “Old Godey Lime Kiln” for sale—basically a giant stone oven and a dream.

By 1907, the fires were out. Maybe a little more lime got sold off in 1908, but the game was up. The Godey Lime Kilns—once a cornerstone of Washington construction—were now obsolete.

Westward view of the Godey Lime Kilns ruins, captured after 1907. This historic photograph, held by the National Park Service, shows the weathered remains of the 19th-century industrial site at the junction of Rock Creek and the Potomac Parkway in Washington, D.C. Source: Library of CongressLaundry, Freeways & Forgotten History

So what happened to the kilns? Some of the wooden sheds and buildings were demolished, but the stone ovens were too stubborn to disappear. By 1908, the Sterling Laundry moved in, turning the site into a sudsy, steam-filled complex. But the kilns stayed put, standing behind the laundry like ghostly remnants of a dirtier past.

Fast forward to the 1940s and 50s. Freeway madness hit D.C., and engineers nearly demolished the kilns to make way for the K Street expressway and the Whitehurst Freeway. Two of the four kilns were bulldozed, and the remaining pair were buried up to their chins—fire doors and all.

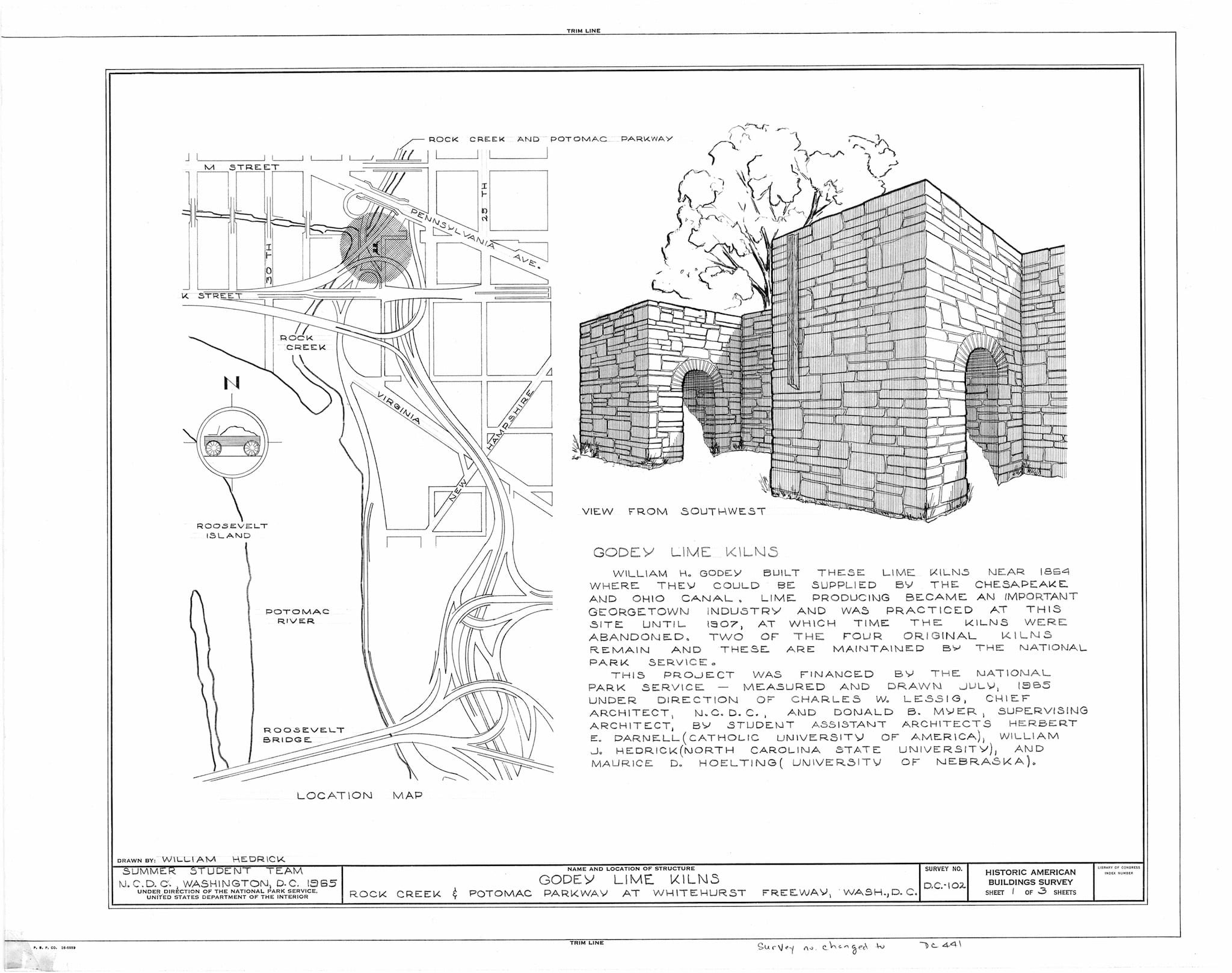

Miraculously, preservationists stepped in. In 1965, the Historic American Buildings Survey swooped in, snapping photos and making architectural drawings. The National Park Service restored the surviving kilns in 1967, saving what little was left. And in 1973, they officially made the list—National Register of Historic Places, baby.

Hidden in Plain Sight: Visiting the Kilns Today

So where are they now? Still there—just barely. The remaining two kilns squat near the Rock Creek Parkway, hugged by on-ramps and overpasses. Ivy creeps over their stone walls. The arched openings are half-buried. Unless you know where to look, you’ll probably miss them.

Visiting them is tricky. There’s no trail, no sidewalk, no safe crossing. The National Park Service basically says, “Don’t try it.” But if you’re brave (and nimble), you can approach from the dead-end of L Street NW. Just know you might be hiking through trash and weeds.

Most folks catch a glimpse from the car—a blink-and-you-miss-it view from Rock Creek Parkway. But if you do see them, tip your cap. Those kilns helped build the city you’re driving through.

D.C.’s Industrial Soul, Still Smoldering

The Godey Lime Kilns are weird. They’re old. They’re hard to get to. But they’re also one of the last surviving pieces of a city that once had an industrial backbone. Before D.C. was all marble columns and lobbyists, it was smoke, stone, and sweat.

These kilns tell a story most people don’t know—a tale of immigrant entrepreneurs, chemical fire, urban expansion, pollution battles, and preservation wins. The next time you’re driving up the parkway near the Kennedy Center, glance toward the riverbank. Those arches? They’re not ruins. They’re reminders.