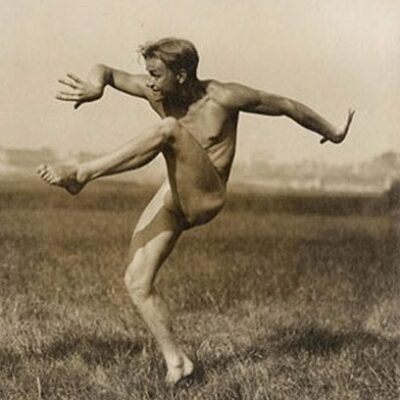

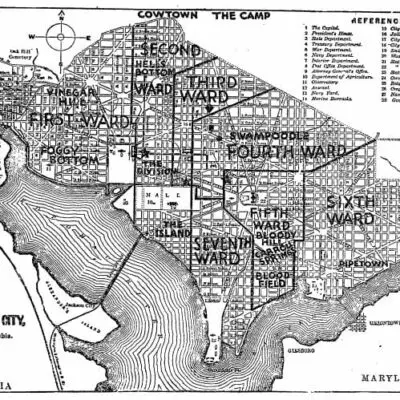

This is a great moment in time captured on film. It’s a group of young men at the Citizens’ Military Training Camp in Maryland, which was a camp to teach young men how to be civilian and citizen soldiers.

I dug up a great article in the Baltimore Sun from October 17th, 1971. The author, James W. Mitchell, had spent summers at the camp and was recounting his experiences in the piece.

Regular Army men called us summer soldiers, or Boy Scouts, or 30-day wonders. We grinned because we were having the time of our lives.

Citizens’ Military Training Camp ran for a month every summer. We were allowed a nickel a mile travel expenses to get to and from camp. The government clothed and fed us, gave us a bed and what medical attention we needed. We marched, hiked, drilled and learned to fire a Springfield ’03 rifle in summer heat so fierce that husky men and boys keeled over from sunstroke.

We weren’t paid a dime for learning to soldier, yet the comparatively few chosen from the many who applied for CMTC every year were considered the luckiest boys in town.

The camps were set up to train and condition young men, as a sort of citizens’ army, in 1915. Applicants could be no younger than 17, had to have a good general intelligence and moral character.

…

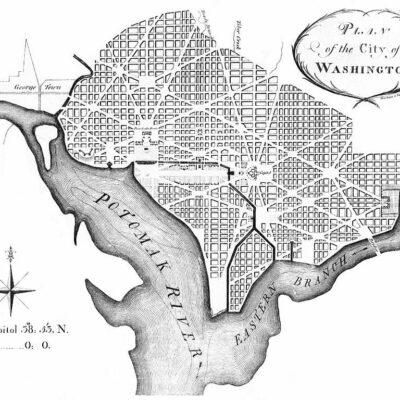

In 1929, when I was 18, I lived in Confluence, a small place near Uniontown, Pa. My brother Charles and I went to camp that year with other men of the Third Corps Area, which took in Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and the District.

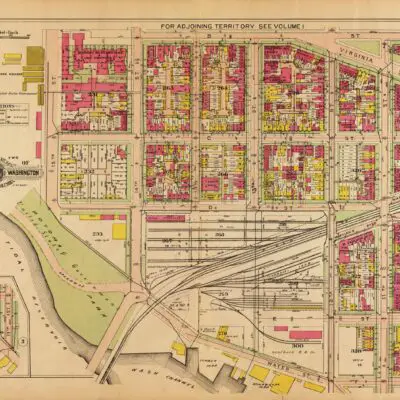

Our camp was at Fort Washington, 14 miles south of Washington on the Potomac River. It had been one of the original CMTC camps. Many buildings were permanent red brick structures. Our quarters were 8-man pyramidal tents.

…

Money was scarce in those days. My brother and I were lucky. Our father worked for the B. & O., and by riding to camp on the family railroad pass, we got to keep our travel allowance, about $11 each. This was our spending money for the month in camp. It was considered a small fortune, so I deposited my bankroll with an officer in the administration tent and drew from it as I needed it.

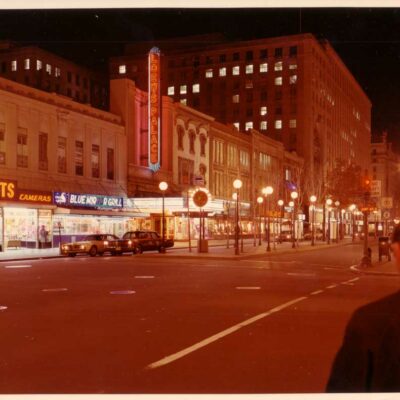

A little money went a long way. I could draw out a dollar, ride into Washington on the General D. H. Rucker, the camp passenger boat, see a movie, have a sandwich, do some sightseeing, and then have a dime left for a ham or bologna sandwich to eat on the boat trip back to camp.

For many of us, CMTC was our first extended stay away from home, but soldiering was a thrilling business, and we took readily to the Army way–“The Army goes as far as it can–and then keeps going.”

Actually, it wasn’t too rough. Reveille was at 5:45 A.M. We worked hard in the morning on military instruction and skills. After noon chow there was one compulsory hour of participation in some prescribed sport, and then we could spend the rest of the afternoon in exercise of our own choosing–baseball, basketball, track, volleyball or swimming. We dressed for a retreat formation at 5 P.M., and then were on our own until call to quarters at 10 P.M.

…

My brother and I went back to camp in 1930 for another wonderful month. That time our battalion assembled on the White House lawn and we had our picture taken with President Hoover.

For one reason or another–it might have been some minor surgery, or perhaps it was my growing interest in the game called baseball–I didn’t go back to camp the following summer. The CMTC program was disbanded about the time the country began drafting soldiers for World War II.