This is a guest post by Aaron. He also wrote a really popular post on red metro trains.

It must have made a splash. But nobody saw anything. An overturned taxi lay atop the rocky shore of the Potomac. There it was. No driver and perhaps no obvious clues within. But it didn’t take long for police to grab a suspect.

It was early Wednesday morning, February 17, 1937. Detectives tracked down the taxi’s owner, Clair A. Kensinger. They saw the cabbie’s Pennsylvania Avenue address — and they knew instantly. This was revenge.

Just 8 hours earlier, police had raided the very same address, 2423 Pennsylvania Ave., NW. They bust through the door of a secret gambling headquarters on the third floor. It was the counting room for a “numbers” game — a million-dollar illegal lottery. Cops were hunting for alleged kingpin Emmitt Robert Warring. A tipster had said he visited the gambling hideout at 7:30 each night. The Post described what police found inside:

“They confiscated elaborate office equipment, an expensive coin auditing machine and nearly $2,000 in cash… but Emmett [sic] was not in the place.”

The gang’s boss remained at large but a new mystery developed.

Eight hours after the raid at the Warring headquarters a taxicab was found in the Potomac River near the Titanic Memorial. Police investigation disclosed the cab is owned by C. A. Kensinger, who lives on the second floor of the Pennsylvania Avenue house directly under the gang rendezvous.

Kensinger asked Capt. Miller for the protection of a policeman after his automobile was found.

“I’m certain those gamblers must think I turned them in,” he said, “but I didn’t know what was going on up there.”

Maurice Sweeny, 3232 Thirteenth Street Northwest, self styled “numbers” writer, who police said is a brother of John Sweeney, Warring gangster who is now in Lorton Reformatory, was arrested and is being held at the Third Precinct for investigation.

He denied having any knowledge of the taxicab being pushed into the Potomac, and told police he did not even know Kensinger. He was fingerprinted and photographed at Police Headquarters where records show he had not been arrested previously.

The Warring gang had clearly fingered their downstairs neighbor as the snitch. History doesn’t tell us exactly how this all panned out, but news reports indicate Clair Kensinger’s cab was taken in the middle of the night. He slept in his home as the car was pushed from the 2400 block of Pennsylvania Ave. to a spot on the river where the Kennedy Center now stands — about 5 or 6 blocks.

The Warring gang had clearly fingered their downstairs neighbor as the snitch. History doesn’t tell us exactly how this all panned out, but news reports indicate Clair Kensinger’s cab was taken in the middle of the night. He slept in his home as the car was pushed from the 2400 block of Pennsylvania Ave. to a spot on the river where the Kennedy Center now stands — about 5 or 6 blocks.

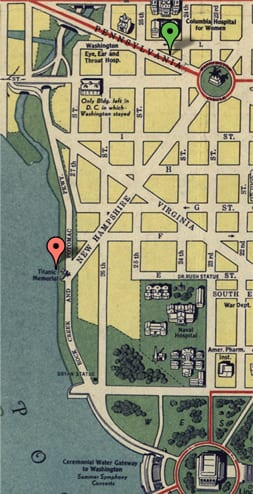

This map shows the street layout around the time of the crime — with a green marker at the cabbie’s home and a red marker noting the approximate resting place of his vehicle. (This comes from a must-see 1942 map of the District’s tourist areas distributed by Esso service stations.)

What happened to Maurice Sweeney?

Of all the Warring gang members, why did Maurice Sweeney get the collar for the taxi theft? It probably didn’t help that a 1936 city directory listed him as an “auto mechanic.”

By the summer, a grand jury indicted Maurice S. Sweeney for his role in the destruction of the cab. The Post wrote about the charges on July 3, 1937 under the headline, “Man Is Indicted For ‘Revenge’ Wreck of Taxi.” And that was it. Maurice Sweeney disappeared from the news for a few years.

The 1940 Census indicates Sweeney and his wife Frances continued to live on 13th Street. He wasn’t in jail. But Sweeney was still working with engines. He told a census taker his profession was “moving van proprietor.”

In 20 years, he never strayed far from the scene of the taxicab crime. Maurice “Buddy” Sweeney went on to work at a Foggy Bottom tavern named Pete’s Restaurant for many years. When the eponymous Pete died in 1951, Sweeney became the manager and eventually the restaurant’s owner. He later moved the place to 2532 F St. — just blocks from the 1937 taxi dumping spot.

In 20 years, he never strayed far from the scene of the taxicab crime. Maurice “Buddy” Sweeney went on to work at a Foggy Bottom tavern named Pete’s Restaurant for many years. When the eponymous Pete died in 1951, Sweeney became the manager and eventually the restaurant’s owner. He later moved the place to 2532 F St. — just blocks from the 1937 taxi dumping spot.

A bit of research reveals that Sweeney may have stayed in close contact with gambling kingpin Emmitt Warring. By 1951, Warring was a notorious local crime figure. His District-wide illegal numbers racket continued to grow. The Post told his life story in a multi-part series as Warring faced federal tax evasion charges in March 1951. One article pinpoints Warring’s favorite spots for secret meetings with police officials (several were allegedly on his payroll). Where did Warring chat with one top detective? You guessed it: Pete’s Restaurant.

It gets more interesting. At trial, the gambling boss contended he didn’t owe taxes on $250,000 stashed in his safe deposit box. That cash, Warring said, belonged in part to two men who were partners in his business. But the government never sought those men — because they doubted their existence. What names did Emmitt Warring provide as 50% stakeholders? “Prim” Kyle and “Buddy” Sweeney. Neither was sought as a witness.

Maurice S. “Buddy” Sweeney suffered a heart attack and died in 1960. He remained ostensibly in the restaurant business until his death. The Post obituary on November 20, 1960 ended with a bit of unintentional irony and details about a guy who worked hard and honestly in Foggy Bottom. Well…. maybe not so honestly.

His customers included actors from Arena Stage, socialites, police, cab drivers, White House personnel, and others and he knew most of them by name.

Mr. Sweeney was on the job six days a week, opening early for customers in search of breakfast or beer. He usually ate dinner at home, rested, and then returned to the restaurant.

It was during this rest period that he was stricken Friday.

Emmitt R. “Little Man” Warring spent nearly 3 years in prison in the early 1950s. A separate trial in 1955 landed him back behind bars for an additional year. He died in 1974 from a self-inflicted gunshot. His Post obituary quoted from the newspaper’s extensive 1951 series on the crime boss:

Emmitt R. “Little Man” Warring spent nearly 3 years in prison in the early 1950s. A separate trial in 1955 landed him back behind bars for an additional year. He died in 1974 from a self-inflicted gunshot. His Post obituary quoted from the newspaper’s extensive 1951 series on the crime boss:

“This is the story of a man of importance and influence in Washington. He is a financial success in a multi-million dollar local business; a contributor to many local causes; the employer of hundreds of workers; the first-name intimate of policemen, lawyers and leading citizens. His illegal numbers game is patronized by tens of thousands … He has been a hidden power and a secret force in this city. Citizens need to know who, for good or evil, influence their daily lives.”

The cabbie, Clair A. Kensinger, never reappeared in the news. He died November 13, 1945 at age 56. Kensinger was a World War I veteran and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.