This has less to do with the history of our city, but everything to do with the (almost) history of our nation.

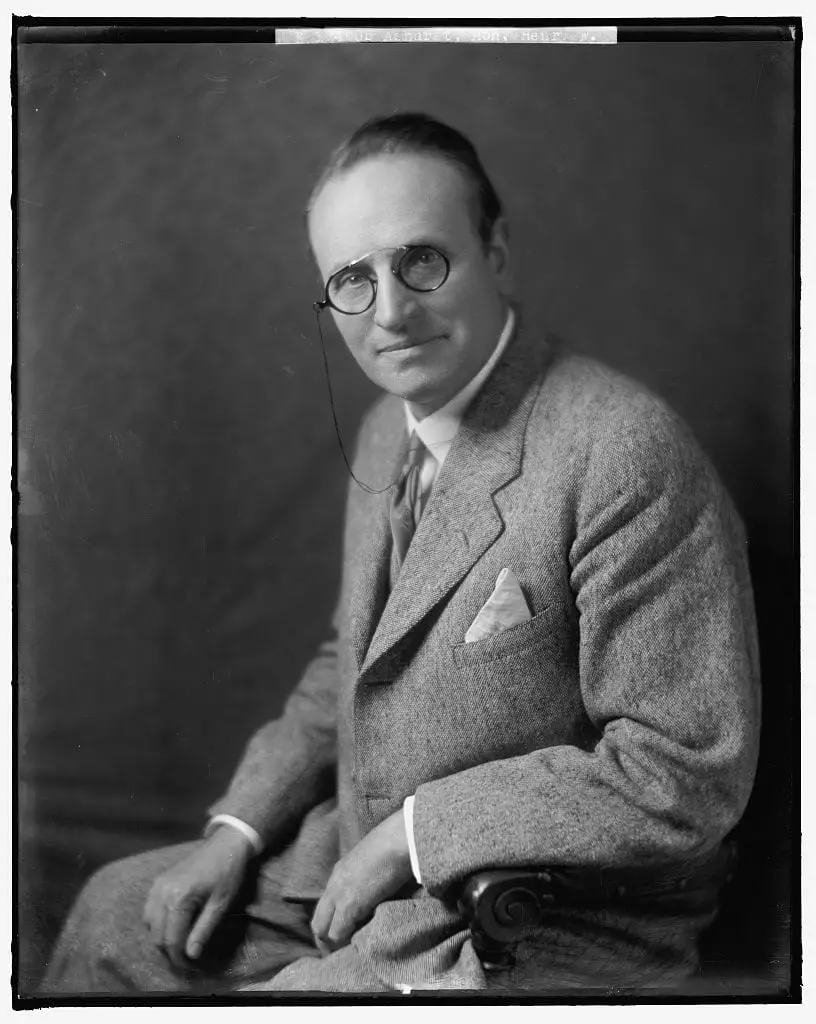

Arizona had been admitted to the union only a few years earlier in 1912 and by the middle of the decade, the two new senators, Marcus Smith and Henry Ashurst, were strongly advocating to acquire Mexican territory south of their young state.

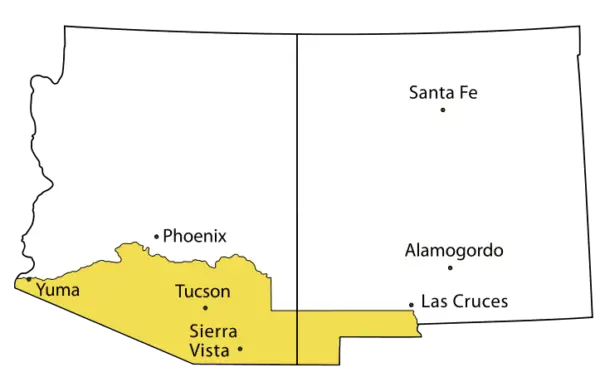

The current border between Arizona and Mexico was set with the Gadsden Purchase in 1853, pushing the boundary farther to the south. The eventual agreement to acquire territory was far less land than the original goal. The agreed upon deal was one of three proposed treaties between the neighboring countries.

The treaty was known simultaneously as the “skeleton” treaty, giving the current south portions of Arizona and New Mexico in exchange for $10 million in gold.

One alternate proposal was to extend the existing southern horizontal border, below Sierra Vista, in a direct line to the Gulf of California in exchange for $15 million. This proposal would have given Arizona a port and ocean access.

The other was to start at a point south of El Paso, Texas and move west along the 31st parallel to the Gulf of California, including the entirety of the Baja California peninsula (i.e., Cabo would be part of America).

Senator Ashurst wanted to revive the latter proposal, both for the benefit of his state and the union. This was partly driven by Manifest Destiny and expansionism, but it was also heavily influenced by geopolitical concerns. America, and especially its western states, were keeping their eyes on a rising power in the Pacific — the Empire of Japan.

Japan, a technologically inferior and backwards country just 50 years earlier, was flexing its muscles in a big way. Less than a decade earlier, they had defeated the Russians in the first major 20th century war, significant because it was the first time an Asian country defeated a European nation in modern warfare. The formerly isolationist country was looking outwards in a big way with eyes on establishing colonies across the Pacific in Mexico.

In the late 1890s, Japan was working, with the Mexican government’s full cooperation and encouragement, to establish agricultural settlements throughout Mexico. The eastward expansion of the Empire of Japan was a clear and present threat to the United States’ dominance over North America. On March 12th, 1916, the Washington Post printed an article discussing the potential acquisition being discussed.

The interesting fact leaked out yesterday that Senator Ashurst, of Arizona, backed by several Western senators, has urged President Wilson to renew negotiations with Mexico for the purpose of obtaining a small slice of the norther portion of Mexico. The plan proposed by the Arizona senator is in line with one of the treaties negotiated by James Gadsden, but which was not sent to the Senate by President Pierce. Under that treaty Mexico agreed to sell the United States all that territory lying north of the thirty-first parallel and the peninsula of Lower California.

…

In addition, and equally important, all the strategic naval bases, including Magdalena Bay, along the coast of the peninsula would pass into possession of the United States.

…

One political advantage of such a purchase would be the transfer to the United States of Magdalena Bay, where the Japanese are said to be colonizing.

It would give the United States control of the Gulf of California, straighten out the boundary line all along the south and throw over a comparatively narrow strip of the finest land in northern Mexico to American enterprise and capital.

in the waters of Lower California are said to be some of the finest fishing on the Pacific coast, which would afford another field for American industrial development.

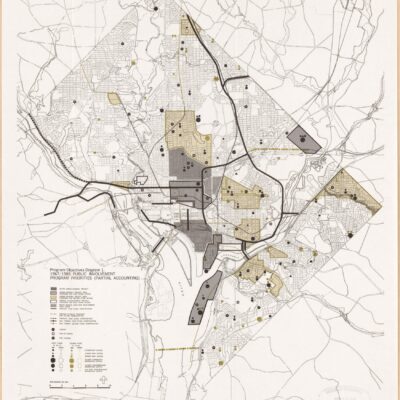

The Google Map below highlights Magdalena Bay and the territorial region focused on by Ashurst.

The land acquisition championed by Senator Ashurst was almost 10,000 square miles, taking the entirety of Baja California and a large chunk of the Mexican state of Sonora.

The fears of Japanese incursion through colonization were not unfounded, but there was another, even more real threat.

Mexico was in the midst of their decade-long revolution, starting in 1910, and this had major economic and security implications for the United States. The former was an issue because, at the time, more than a quarter of the land in Mexico was owned by American interests. Unrest due to the revolution had serious economic consequences in our country and there was major political pressure on both congress and President Wilson to intervene. The latter was was a grave concern for Ashurst’s constituents and those of his neighboring states.

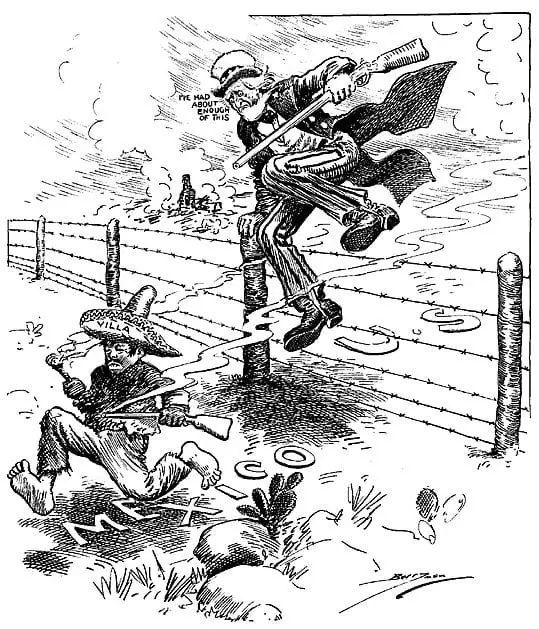

There was a real threat of cross-border raids into U.S. territory, which manifested itself in an attack by Pancho Villa’s forces on Columbus, New Mexico in 1916. Information was not always accurate and frequently was speculative, but Villa’s attack on American soil created explosive outrage in congress and in public opinion.

Troops, led by General Pershing were sent to hunt down the raiders, with no success, until they were eventually called into another, greater conflict in Europe — World War I.

The lawlessness of Mexico during the revolution, the raids and border incursions leading to the deaths of American citizens, North American colonial aspirations of Japan, and the massive war between colonial empires in Europe during World War I provided Ashurst with ample ammunition to make his case for territorial acquisition. The Great War shifted the country’s focus for a few years, but by 1919, the senator was back with a drumbeat to make the strategic acquisition.

The Washington Post, on January 8th, 1919, wrote about Senator Ashurst’s drive to acquire the land.

Washington, Jan. 7.–Speaking in the Senate today in support of his resolution for acquisition by the United States through negotiation with Mexico of lower California and part of the State of Sonora, Senator Ashurst, of Arizona, declared the Mexican Government was unable to control the territory of protect it from foreign invasion. Annexed to the United States, he said, it could be converted into immense agricultural value by irrigation from the Colorado river.

Lower California, said the Senator, is “the vermiform appendix of Mexico and the Achilles heel of the United States.”

The Mexican republic is both unwilling and unable to police the peninsula, he added, and is unable to resist aggressions from or settlement by oriental powers; hence the base of supplies or of military and naval operations, with comparative ease and secrecy, could be established among the numerous islands of the Pacific Coast.”

The threat of a foreign base appearing on the shores of Mexico was great rhetoric to stoke the flames of fear in the immediate aftermath of the greatest war known to man, but it was really just theoretical. Small settlements and potential for colonies existed, but bases were not truly taken seriously by the mainstream.

Ashurst was doing his best selling his idea on the floor of the United States Senate and throughout Washington, wherever and whenever he could. In a hotel lobbies piece in the Washington Post from June 8th, 1919, Senator Ashurst was making bold claims, while visiting the Willard Hotel, that Lower California would become the 49th star on the American flag.

“Lower California will become a part of the United States, adding another star to our flag, and at no far distant day,” declared Senator Ashurst, of Arizona, at the Willard.

…

“The Mexicans recognize that their government has paid no interest on its bonds since 1912, having defaulted in 1913 and all subsequent years. Nearly all Mexican business men are anxious that a sale of the peninsula be made, so that Mexico may obtain funds with which to discharge her national obligations and stabilize her credit, and thus assist in restoring Mexico to a place among the family of nations.”

Despite Ashurst’s push to expand the country both south and west of his home state, we know the eventual outcome and the outline of the current map … but Ashurst never gave up his fight.

He tried to push for territorial acquisition again in 1931, much to the disgust and insult of many Mexican legislators. Their response was to introduce bills into their own legislature to buy Ashurst’s home state of Arizona and request the United States throw in Texas, New Mexico and California for good measure (I enjoy the humor of that posturing).

In 1938, there was another movement driven by Colonel William H. Evans of Los Angeles, and supported by Ashurst, to acquire the land … of course, that too failed to gain acceptance.

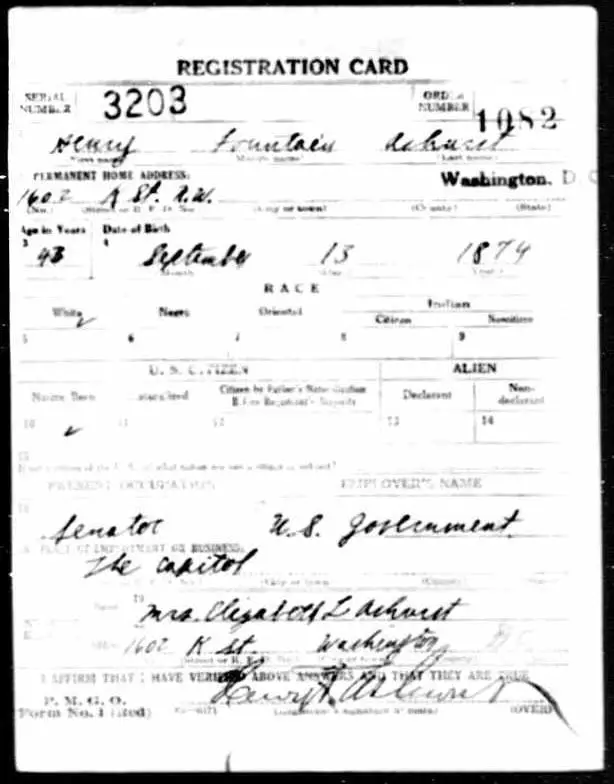

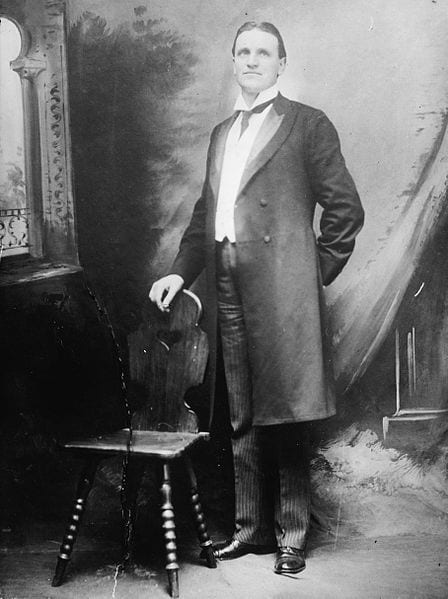

Senator Henry Fountain Ashurst was a tenacious and persistent cowboy, who literally was born in a covered wagon back in 1874. He was one of Arizona’s first senators, serving from the state’s admission to the union in 1912 until 1941 — early in his tenure, he made sure to fulfill his patriotic duty and register for the draft (see the scanned image of the draft card below).

Imagine if his fears were realized and the Empire of Japan really did set up bases in Mexico. I suspect that Pearl Harbor and World War II would have had vastly different outcomes. Who knows, maybe the former would never have happened and the latter could have been kicked off with a land invasion on San Diego.

The senator, originally was to retire back in Arizona after losing his final election, but opted to remain in his Washington residence at 1602 K St. NW, across the street from the famous Chateau Bonaparte. He lived there with his wife Elizabeth — who was originally from Kilkenny, Ireland — until she passed away in 1939 at the age of 65. He lived out the waning years of his life at the Sheraton Park Hotel (i.e., now Marriott Wardman Park) until his death in 1962.