I’ve been trying to dig up this information for a really long time. Thanks to some minor prodding in an email from GoDCer Hugh, I decided to give in one more shot. And, I finally found something on the last farm in Washington, DC.

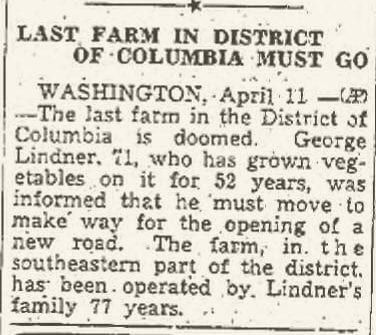

The Ada Evening News, a local paper from Ada, Oklahoma (seriously in the middle of nowhere – no offense if you’re from there) had a really small mention of the last farm in D.C. being forced to shut down. It was printed in the newspaper on Tuesday, April 11th, 1939.

George Lindner, a 71-year-old farmer, had been growing vegetables on the family farm for the last 52 years, which was in southeast. The farm had been in the Lindner family since early on during the Civil War.

It’s odd that after all this time, I had to find out the details behind Washington’s last farm from a tiny newspaper in Oklahoma, but nevertheless, I finally had something to help me dig even deeper and uncover a story to share with GoDCers.

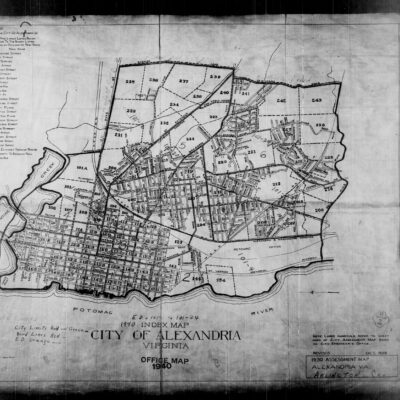

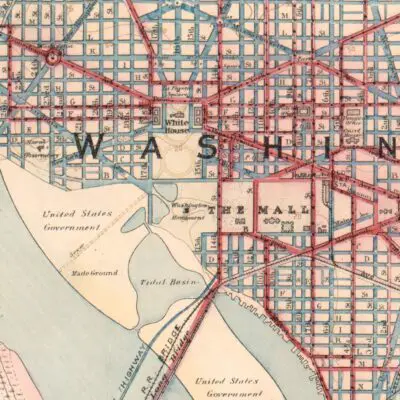

The family farm was located at 3801 Wheeler Rd. SE, and today, it looks like the land has a large apartment building on it, though there is quite a bit of open space on a hill. It also appears that Achievement Prep is on the land formerly owned by the Lindner family.

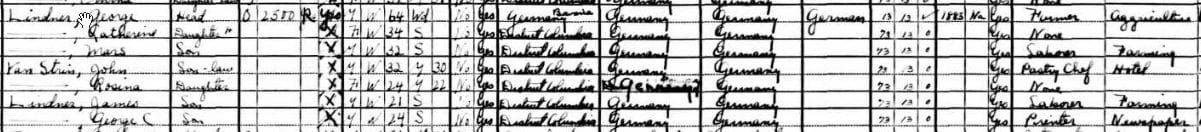

We were also able to dig up the family records in the 1930 U.S. Census. George was born in Germany and came to the United States in 1883. At the time, he was a widower, living with two daughters and three sons.

The Lindner story is like so many others of urban progress. Family has land for several generations, government wants to build a road, family is out of luck.

With the family’s name and the 1939 timeframe, we finally came across a Washington Post article, also published on April 11th.

The last farm in the District is doomed.

The chocolate, loamy earth that George Lindner acquired from his father 52 years ago and worked and watched while it brought to life vegetables for the tables of Washington is soon to disappear to accomodate a highway between Fourth street and Wheeler road southeast.

George Lindner, 71, has a back like a soldier’s, a Bavarian ancestry and a pair of small, gray eyes that can look deeply into a piece of ground t ocall it good earth or not. He has two stout sons, James and Morris, and a daughter, Catherine, who worked with him yesterday, bending low upon the field to place spring seedlings in the ground.

George Lindner called his sons and daughter to help explain what, of a sudden, was occuring. He used the blunt implement that has been easing the shoots into the ground, as a pointer.

“See,” he said, aiming the implement across the field, “the road would start off from there and take right off through here. Five acres would go from here and about seven from over there.” He pointed across the mintbed.

“It’s good ground. My boys here have been raised as farmers. They will have to learn something else to do. We can move, Ja, but where will there be land like this?”

“It is pretty in this valley: it’s like a little paradize here when things are up,” said Catherine. “He worked it for 50 years; Michael Lindner had it first. That was 77 years ago.”

“I worked it for 52 years,” said George Lindner. “In 1918 I had 10,000 celery; and now there are cantaloupes, beets, cabbages, and kale. What will I do; they say a man will be paid and will go someplace else, Ja; but in 100 acres any place else would he find this? That hill up there … I have acres there, but it is a hillside. This is a garden. Now the Park and Planning Commission–is that it?–sends for me; but I’m getting old and I send my son, and he must go back again for another trial.

“You see what I mean? The road–they have to have it–would start right there and come down through my garden. Now mw, ja, I am getting old. I don’t know how to feel, that I’ve got to leave it. But my sons were raised as gardeners and they must go on.”

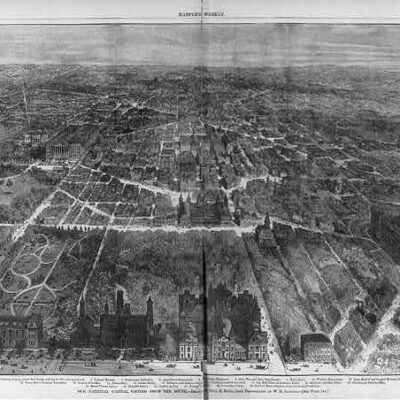

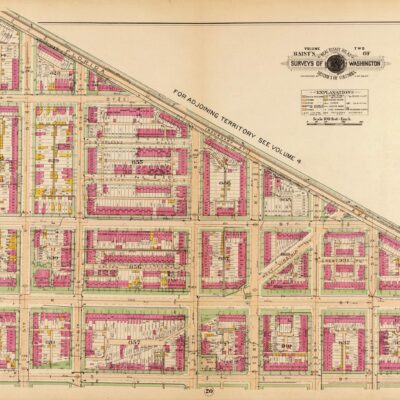

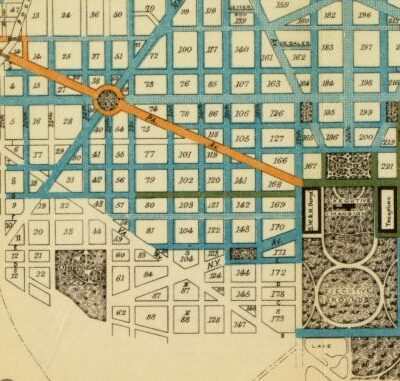

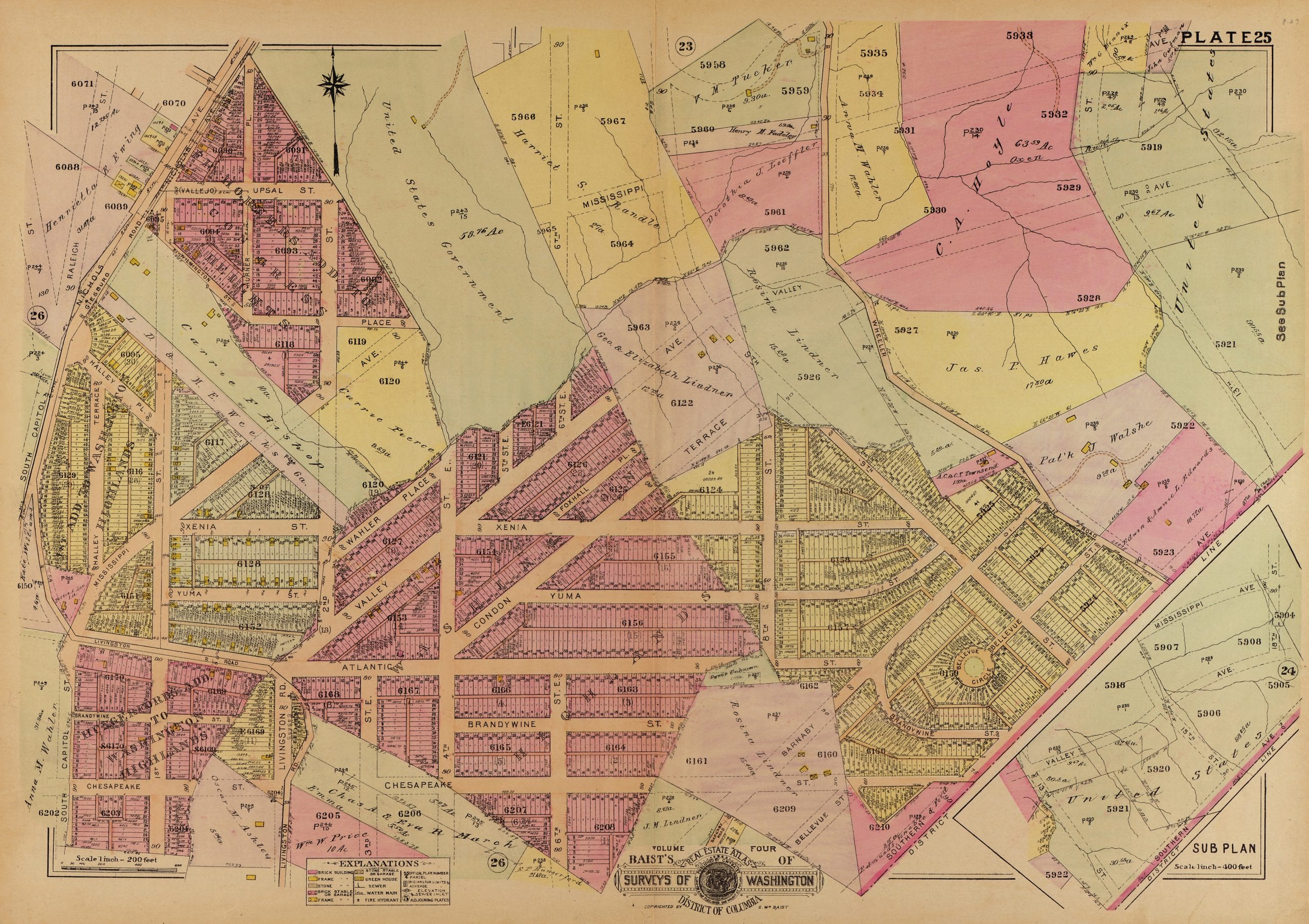

Take a look below at the Baist real estate map of the Lindner family land in 1921. You can see the proposed roads even then, 18 years before the farm was taken over by the government.

For a bigger version of the map, click on the image below. It’s amazing to see how rural the area in southeast was back in 1921.

Source: Library of Congress