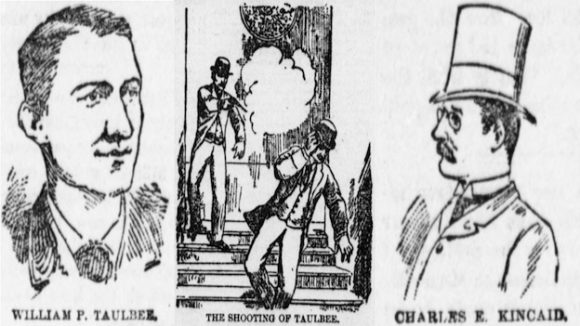

On a seemingly ordinary day in late February 1890, the corridors of the U.S. Capitol, usually echoing with the sounds of legislative debates and political discourse, became the backdrop for a shocking incident that would etch itself into the annals of American political history. This was not a story of policy disagreements or partisan squabbles but a tragic tale of personal vendetta and fatal consequence involving Congressman William Preston Taulbee and journalist Charles E. Kincaid.

The Prelude to Tragedy

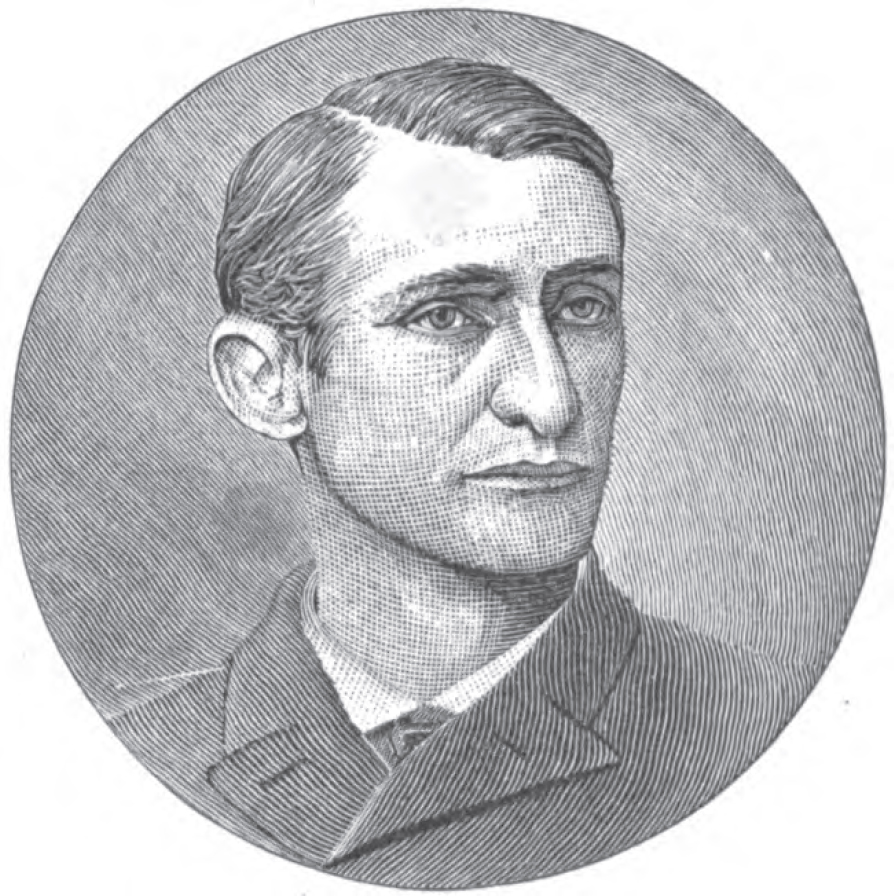

William Preston Taulbee, emerging from the rugged landscapes of Kentucky, had carved a notable path for himself within the political corridors of Congress. Renowned for his eloquence and political savvy, Taulbee was a figure of considerable influence and charisma. Yet, beneath the veneer of public acclaim, a scandal lurked that would ultimately overshadow his accomplishments.

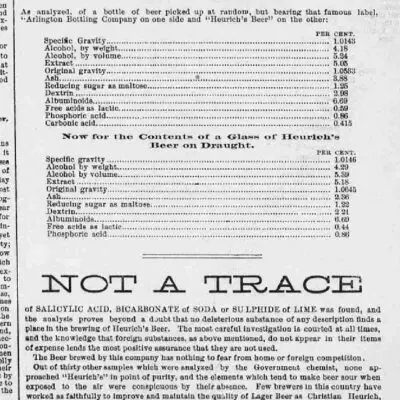

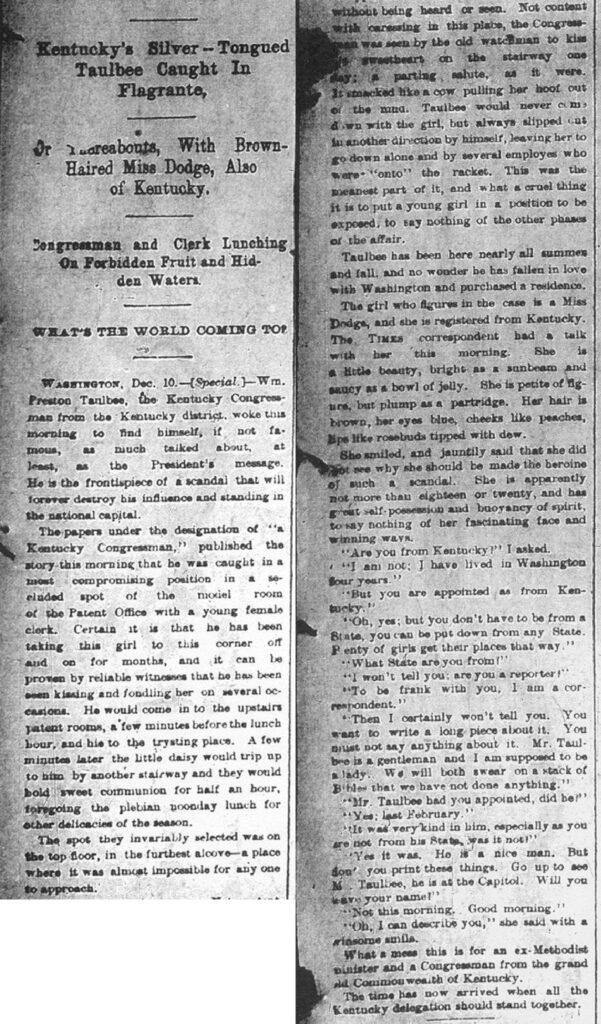

The heart of the scandal was an indiscretion involving a female clerk at the Patent Office, a story that became a sensational topic for the press. Charles E. Kincaid, a correspondent for the Louisville Times, was at the forefront of exposing the affair, which irrevocably damaged Taulbee’s reputation and led to his decision not to seek re-election in 1888. The coverage of the scandal by Kincaid was not just reporting; it became a personal crusade, weaving a narrative that intertwined public outrage with private vendetta.

The ensuing animosity between Taulbee and Kincaid was palpable, a classic clash of personalities and principles. Taulbee, with his imposing physicality, and Kincaid, armed with his pen and wit, found themselves locked in a conflict that was both deeply personal and highly public. The historic halls of the Capitol, accustomed to the ebb and flow of political discourse, were on the cusp of becoming the stage for a far more personal drama.

The atmosphere was charged with tension, a foreboding sense that the ongoing feud might escalate beyond verbal sparring. The relentless pursuit of the story by Kincaid, coupled with Taulbee’s growing resentment, set the stage for a tragic culmination of events. In this charged environment, every interaction was laden with potential conflict, leading inexorably towards a moment of irrevocable consequence.

The Fateful Taulbee-Kincaid Encounter

On February 28, 1890, the simmering feud between Taulbee and Kincaid reached its boiling point. The two men encountered each other inside the Capitol Building, and the moment was marked by a heated exchange that set the stage for the tragic outcome. According to the Evening Star article from a 1936 retrospective article, “The trouble began in the House corridor near the east door where Judge Kincaid had come to send a card to a member on the floor. Taulbee, so an account states, was near the door and accosted Kincaid, calling him vile names and refusing any communication with him, and Taulbee seized him by the ear.” This altercation highlighted the deep-seated animosity between Taulbee and Kincaid, foreshadowing the violence that would soon unfold.

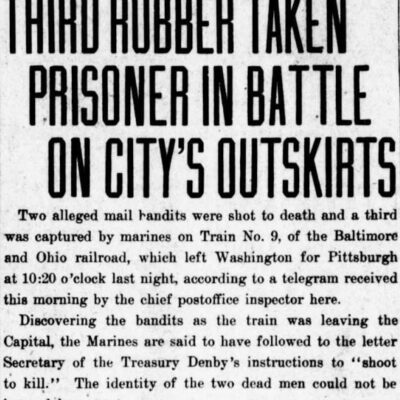

Despite the efforts of Samuel Donaldson, the Doorkeeper of the House, to defuse the tension, the conflict escalated. “About 20 minutes before 2 o’clock, they met again just outside the Capitol near the southeastern entrance to the building. This time Kincaid pulled out a revolver and shot Taulbee in the head, the bullet striking in the vicinity of the left temple and coming out at the eye,” reported the Evening Star.

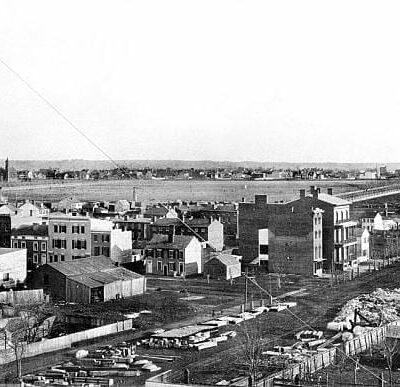

An account from the Evening Journal of Wilmington, DE, vividly captures the chaos: “A pistol shot that echoed through the lofty corridors of the Capitol; a man staggering down the marble steps, his face covered with blood…” The marble staircase, typically a silent witness to the comings and goings of the nation’s lawmakers, became the unexpected stage for this dramatic clash.

The gravity of the situation became apparent as Taulbee lay wounded, his blood seeping into the stone. Kincaid, standing firm in the aftermath, openly admitted to the act, making no attempt to flee the scene. Taulbee’s initial prognosis did not suggest the wound was lethal; he was first taken to his residence and then subsequently Providence Hospital. To this day, it is rumored that the marble steps still bear the indelible marks of Taulbee’s blood, serving as a somber memorial to the tragic events of that day and the ultimate price of personal disputes that spiral out of control within the sphere of public service.

Arrest of Kincaid and Death of Taulbee

Following the tragic shooting, Charles E. Kincaid was arrested and faced a murder charge, a situation that captivated the nation and raised profound questions about personal honor, the influence of the media, and the complexities of political life in the late 19th century. Kincaid’s defense, as detailed by the Evening Bulletin on March 26, 1891, centered on the argument of self-defense, casting Taulbee as the provocateur in the deadly altercation. This defense, juxtaposed against societal norms that esteemed honor and sought retribution, led to Kincaid’s eventual acquittal, igniting discussions on the essence of justice and the responsibility of those in power.

In the aftermath of the shooting, William P. Taulbee’s health rapidly declined, culminating in his death on March 11. The Evening Star provided a poignant account of his last moments, noting, “His suffering had been something terrible during this time; delirium, however, mercifully took away the consciousness of pain.” Surrounded by his brother Dr. Taulbee, his son James, and close associate Major Blackburn, Taulbee was engulfed in delirium, unable to articulate any final sentiments, leaving a profound silence on the true repercussions of their longstanding conflict.

The Evening Star further detailed the harrowing conditions of Taulbee’s final night, reporting, “Dr. Coomes, the house physician at the Providence hospital, was with Mr. Taulbee up to 4 o’clock. He says the dying man was delirious during the entire night and seemingly suffering intensely.” The uncertainty surrounding Taulbee’s exact cause of death added a layer of intrigue to the already tragic event, with plans for an autopsy to shed light on the matter: “Just what the final cause of death was cannot be determined until after the autopsy…” This uncertainty, coupled with the speculation of inflammation at the brain’s base, deepened the tragedy of Taulbee’s demise, highlighting the irreversible toll of the dispute.

Kincaid’s Trial and Aftermath

The trial of Charles E. Kincaid, charged with the murder of William P. Taulbee, unfolded with intense public scrutiny in the District of Columbia Criminal Court. Kincaid’s defense hinged on a plea of self-defense, a narrative supported by his own compelling testimony on the stand. “As soon as we recognized each other,” Kincaid recounted, “Taulbee came toward me…I said: ‘You are going to kill me, are you?'” His vivid description of the moments leading to the shooting painted a picture of a man cornered, acting out of sheer survival. Kincaid’s assertion that Taulbee was “within reaching distance” when the shot was fired highlighted the immediacy of the threat he perceived.

The courtroom was rife with tension as witnesses took the stand, each adding layers to the story. Samuel Donaldson’s testimony offered insight into the prelude to the confrontation, while another witness, a farmer from Alleghany County, provided a differing narrative, suggesting Taulbee had aggressively advanced on Kincaid. The trial was not just about the facts of the case but also about the character of the men involved. Kincaid, described as “nervous, delicate, and in poor health,” was portrayed by W. E. Curtis, a respected journalist, as “an amiable, peaceful, and quiet man,” further complicating the public’s perception of the defendant.

After deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of not guilty, a decision met with subdued relief in the packed courtroom. Kincaid’s acquittal was a moment of vindication, not just for him but for his steadfast supporters who had filled the courtroom daily. The Alexandria Gazette captured the solemnity and the relief of the moment, noting how Kincaid personally thanked each juror, a gesture underscoring the deep gratitude and the weight of the trial’s outcome on his shoulders.

The trial’s conclusion was marked by Charles Kincaid being embraced by a circle of friends and family, with their expressions of congratulations tinged with tears of relief, a sentiment deeply shared by his sister, who had been steadfast in her support throughout the trial. This moment of vindication, underscored by the profound joy and relief at Kincaid’s acquittal, unfolded against a complex backdrop of discussions about justice, the power of the press, and the entanglement of personal conflicts within the public arena.