Why did we knock down half of the amazing buildings in Washington? It’s tragic and depressing when you read through John’s book “Lost Washington” or James’ book “Capitol Losses.” Sadly, the home below was torn down and replaced by something substantially less appealing in the 70s.

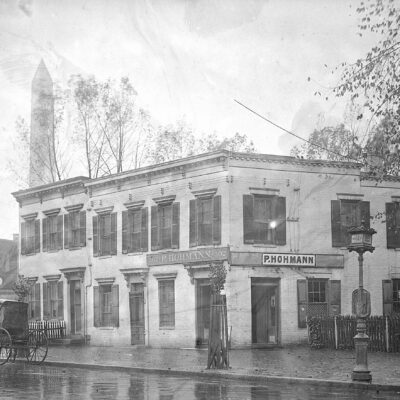

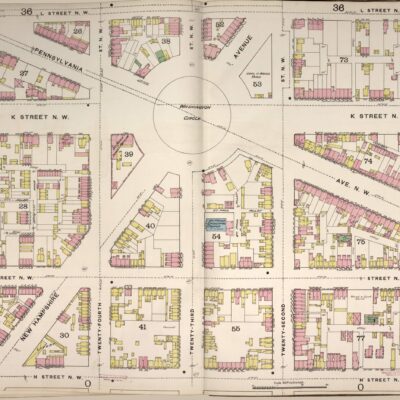

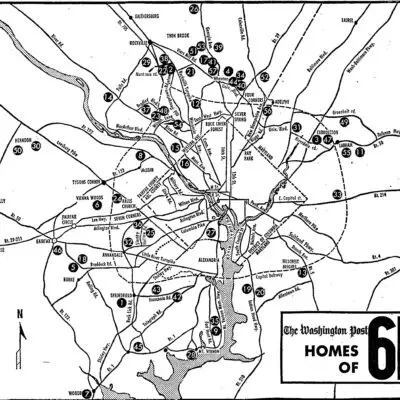

One of our early GoDC readers, Betsy, sent in a request the other day to do a little research on the Stickney House formerly situated at the northwest corner of 6th and M St. NW (601 M St. NW). After seeing the photo below, I wholeheartedly agree that we need to do a little digging on this lost gem.

William Stickney (1827 – 1881) was a prominent member of Washington society, heading up the National Savings Bank of Washington. He also served as secretary of the Board of Indian Commissioners, secretary and director of the Institution for the Deaf and Dumb (Gallaudet University), secretary and treasurer of Columbian University (GWU) and president of the Legislative Council of the Territorial government of the District of Columbia. As you can see, he was a heavy hitter in D.C.

William was originally from Maine, but had arrived in Washington as a young man. He originally attended Waterville College in Maine (now Colby College) and arrived in D.C. to finish his education at Columbian College (GWU).

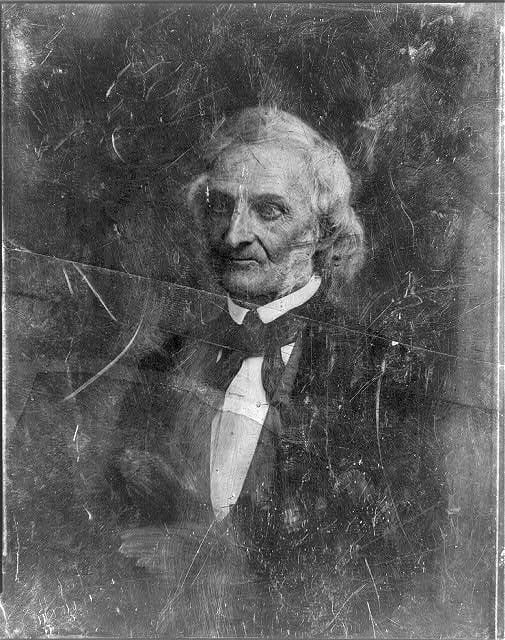

Stickney worked as a government clerk for some time in the 1850s and came into some good fortune when he became the personal secretary to Amos Kendall, Postmaster General under Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren, as well as the co-founder of the institution that would become Gallaudet University. Not only was he fortunate enough to be the right-hand man to a Washington power player, he also became his son-in-law by marrying his daughter Jeannie.

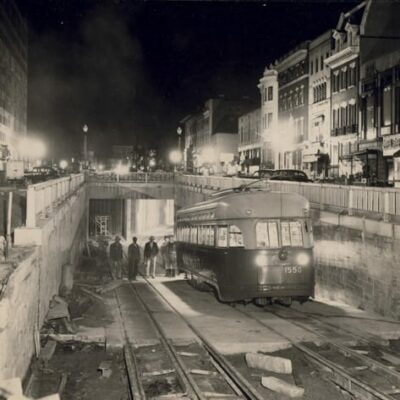

By the late 1860s, Stickney had a solid standing in Washington society and was pulling in a fair bit of money. With his growing wealth, in 1868, he contracted with Adolph Cluss‘ architectural firm to design his mansion at 6th and M. Cluss was the most prominent postbellum architects in the city and his homes often cost upwards of $10,000, an enormous sum of money at the time.

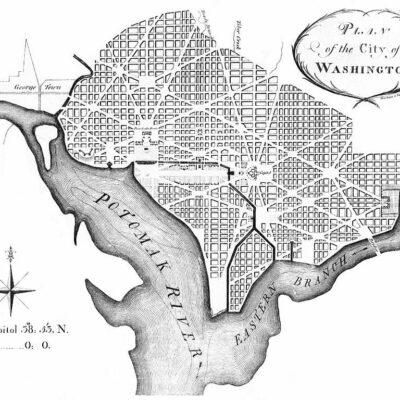

Stickney spared no expense, with his home costing $30,000. The ten bedroom home was built with all the modern amenities of the time to rival the grandest homes of Washington — iron windows and door frames, a wine cellar, library, hot and cold water and a hot-air furnace. Crowning the home was a cupola with a 360-degree view of the city and a straight sightline to the Potomac.

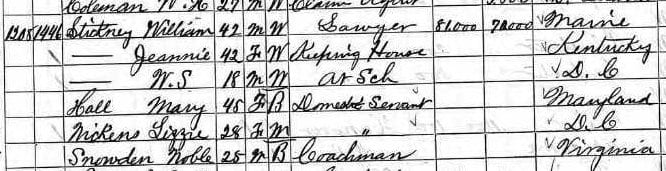

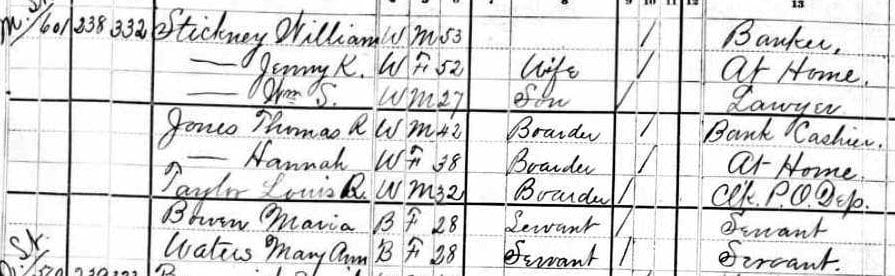

In the 1870 Census, the household included their son William Soule, born in 1852. What’s even more astonishing in the record is that his property was valued at $81,000 and his personal property was valued at $70,000. This guy was seriously rich.

Also listed in the home were two servants, Mary Hall, 45, and Lizzie Nickens, 28, and their coachman Noble Snowden, 25. If you look back at the photo above, it’s very possible that the woman on the far left is Mary and the gentleman wearing what appears to be a hat is Noble. Fascinating.

By the time the 1880 Census was taken, the household had expanded a little bit. Their son, William, had completed his studies and was a full-fledged lawyer in the city. They also took in three boarders, James Thomas, 42 and a bank cashier (possibly at National Savings Bank), his wife Hannah, 38. The Thomas’ originally came to Washington from Pennsylvania. The third boarder was Louis Taylor, 32 and a clerk at the U.S. Post Office. Two servants were also listed, but not the same ones. Maria Bowen, 28, and Mary Ann Waters, also 28.

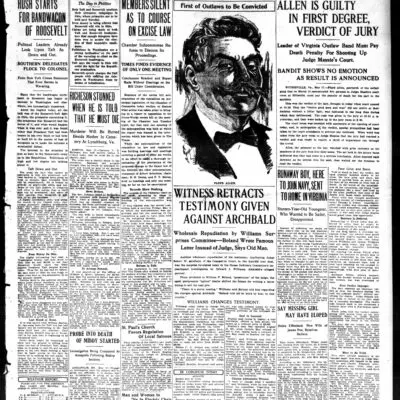

Sadly, there wasn’t too much in the newspapers of the time about the home, but I did come across this article about a robbery in the Washington Post on November 14th, 1878.

Two of the boldest and largest burglaries that have occurred in the District for a considerable time have been committed within the early days of this week. On Monday night the house of Mr. William Stickney, the president of the Nationals Savings bank, situated on the corner of Sixth and M streets, was visited by burglars, who effected an entrance through the conservatory door on M street. They completely ransacked the lower part of the house, carrying away everything valuable that could be carried, principally clothing, and amounting in value to about $460. The front door was left standing open, as was the door at which they had entered. A search in the neighborhood revealed the bulk, if not all the property hidden under a pile of lumber in Willet & Libbey’s yard, on the corner of New York avenue and Sixth street. A close watch was kept on this spot during the following night by the police, and a portion of the articles left as a bait, but to no purpose. Last night, Acting Sergeant Amiss and Officers Marr and Fitzimmons, of the sixth precinct arrested two colored men in the “division” on suspicion. A third, whom they tried to secure, made his escape.

Stickney died in 1881 after a very brief illness. His wife lived out the final years of her life in Monrovia, California and died in 1903.

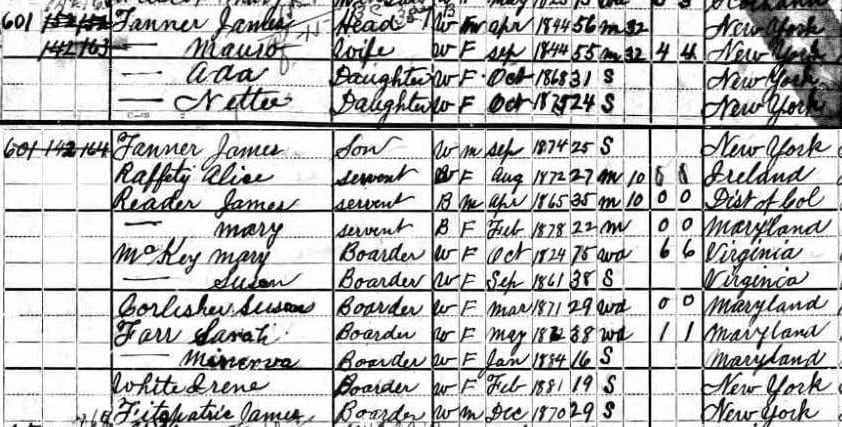

By the early 20th century, Civil War veteran Corporal James Tanner was living in the home with wife Mero, their two daughters Ada, Nettie and a son James Jr. In addition to the family, there were three servants, Alice Rafferty, James Reader and his wife Mary.

The Tanner family also took in boarders and seven of them were staying in the home at the time of the 1900 Census. Mary McKay, a widow from Virginia, and her daughter Susan, who’s occupation was listed as writer. Susan Corlisher, also a widow who worked as a government clerk and another widow, school teacher Sarah Farr and her teenage daughter Minerva. Two more government clerks rounded out the group. Irene White, originally from New York and James Fitzpatrick, also from New York. Three widows in one house?

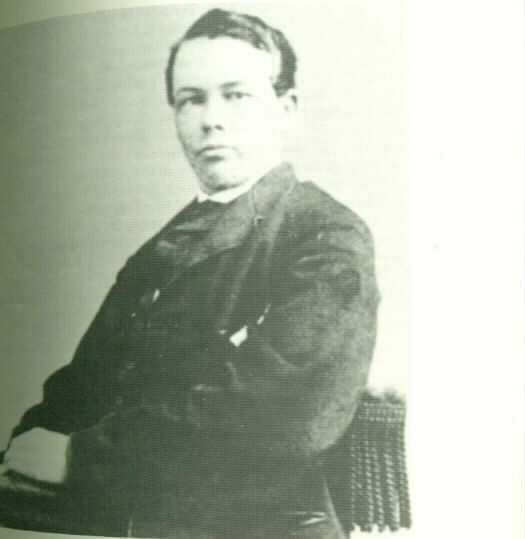

Another interesting fact about Tanner is that he was horribly injured during the Civil War. He was at the Second Battle of Bull Run in Manassas and received wounds so severely that both of his legs needed to be amputated above the knees. He eventually learned to walk again with artificial legs and went on to a successful career in government as a stenographer and eventually attaining his highest position in 1889 as Commissioner of Pensions.

Sadly, he was terrible at his job and had to resign that same year, but went on to a lucrative career as a private pension attorney, making enough money to buy his giant house at 6th and M.

Quick side note for history nerds … he served as a stenographer at Abraham Lincoln’s deathbed in the Peterson House.

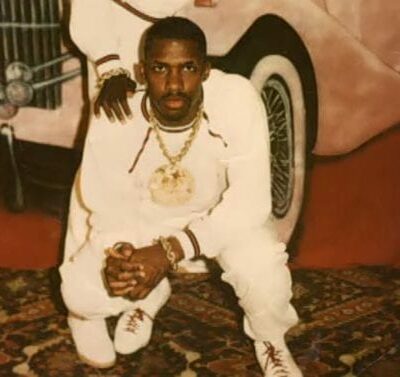

The house at 6th and M was used as a place of worship starting in the 1920s by the United House of Prayer for All People and a home for the founder, Daddy Grace.

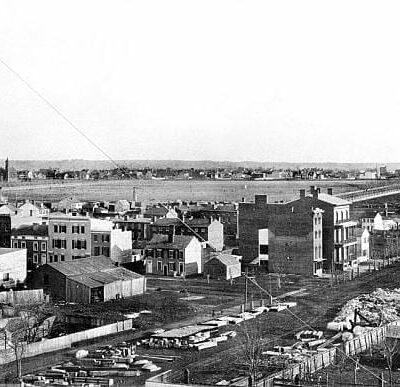

Tragically, the home was razed in 1971 to make way for a new church building. Look what was put up in its place below.