This is the best contribution thus far by a member of the GoDC community. This is from Tom H. in Bethesda, and when I first saw it, I was blown away at how professional it looked. Thanks Tom!

The video is a fascinating history of the gun barrel fence in Georgetown, made from 364 reclaimed Washington Navy Yard muskets.

To complement this wonderful video, we dug up an article published in the Washington Herald on Sunday, June 25th, 1911.

Surmounting a crumbling retaining wall of age-worn stone which stands in front of three of the oldest houses in historic Georgetown is an iron fence which boats a more interesting history than the majority of fencing.

If you will examine the iron uprights standing close together, you will discover that near the top of each one is a projection, which apparently performs no office as a part of the fence. Research into the history of this partition of iron reveals the reason for the projections and many things besides.

Way back in 1814, when Washington was threatened by the invasion of British troops, which were hovering about the ancient hamlet of Bladensburg, Md., foraging and destroying property, the United States government had not the unlimited resources it now possesses.

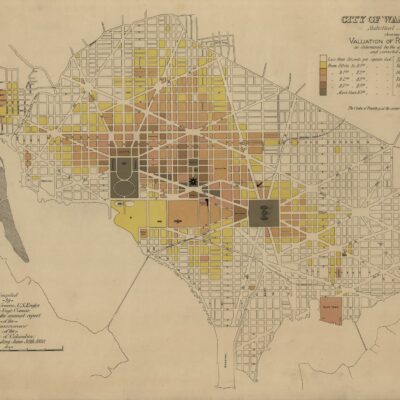

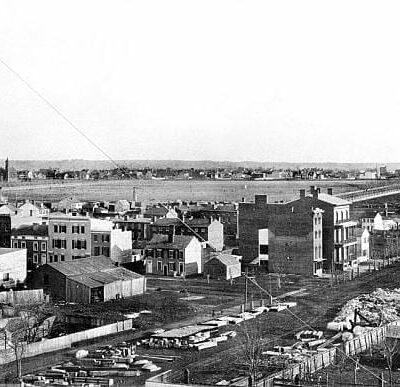

So when the Capital City of the nation was in imminent peril of being destroyed by the hostile troops the authorities here appealed for help to the public-spirited citizens of the locality. Most of the wealth of the District of Columbia was then centered in Georgetown, as at that time it was one of the most important ports of entry of the Southern Atlantic seaboard. There were great shops and mills there in those days. Merchants of Georgetown had thriving business in the Westt [sic] India trade, importing molasses, coffee, sugar, and rum in large quantities. Among the foremost of these big merchants and landowners was Reuben Daw, whose posterity still figure conspicuously in the assessor’s book of Georgetown realty.

Reuben Daw and a number of others immediately advanced money for the defense of the Capital against the invading forces, asking no security from their government. When Washington was invaded by British troops under Col. Ross, shortly after the battle of Bladensburg, when the Americans, under Maj. Barry, were defeated and the Capital burned, the funds advanced by the Georgetown citizens did much good.

When the war of 1812 was over the government was nearly bankrupt and was in no position to repay debts for which no security was held. But the Secretary of the Navy, the commandant of the navy yard, or some officer in authority who was cognizant of the sacrifices made by the Georgetown citizens realized that something should be done for them. There was little that could be done, but it was finally decided to let those who so desired go to the navy yard and take anything in the way of castings that they could use.

Reuben Daw took advantage of this opportunity and asked for a consignment of antiquated flintlock muskets which were rusting in a neglected pile in an old warehouse. He received permission to remove them and took them to Georgetown.

About that time Mr. Daw built the mansion that still stands in Georgetown on P street, between Twenty-eighth and Twenty-ninth streets. Removing the stocks from the old guns, he had plates forged at one end and made them into the fence which still stands in front of the three houses just beyond Twenty-eighth street.

The small projections mentioned are the corroded remains of the sights at the ends of the gun barrels.

The barrels make an unusually serviceable fence, as the length of time they have stood testifies. They are in as good condition to-day as when they were put up, and it would take a good deal of force to knock the old fence down.

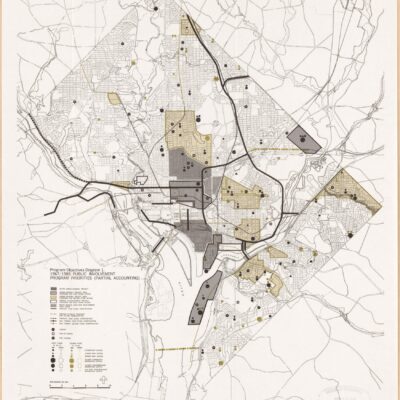

In different parts of Georgetown old iron castings may be seen which came from the navy yard in 1814 or 1815. Window gratings, boot scrapers, stair rails and many other contrivances were fashioned out of the junk taken from the navy yard, and on more than one piece of iron about Georgetown may be seen the coat-of-arms of the United States.

Nearly every on of the castings is directly traceable to the war of 1812, and when one of them is seen it may be taken as mute testimony of the patriotism of the original owner of the property.

Now this a great story. I’m sure the next time you’re walking the brick-lined streets of Georgetown, you’ll be even more observant of these marks of hidden history, connecting us back to the War of 1812.