Here’s a crazy story for you from the 1940s. This was published in the Washington Post on June 4th, 1949.

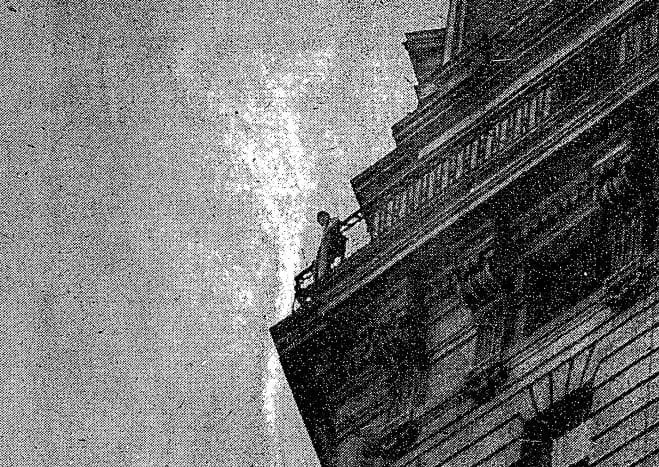

A young Air Force private was grabbed from a ninth-floor ledge of the Willard Hotel yesterday by three policemen who had spent 25 minutes persuading him from plunging to death.

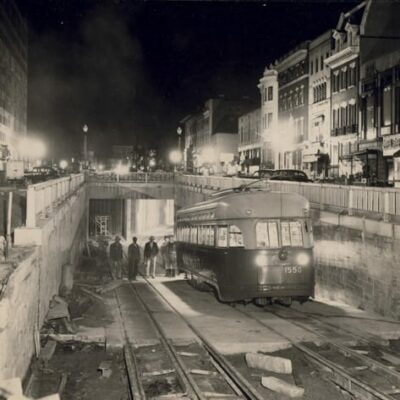

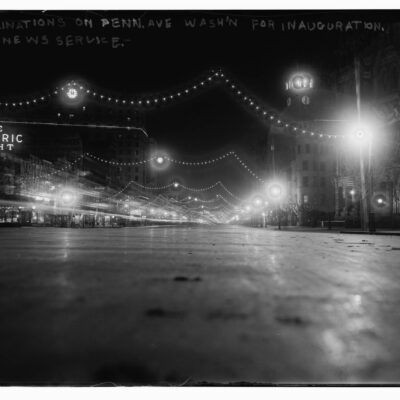

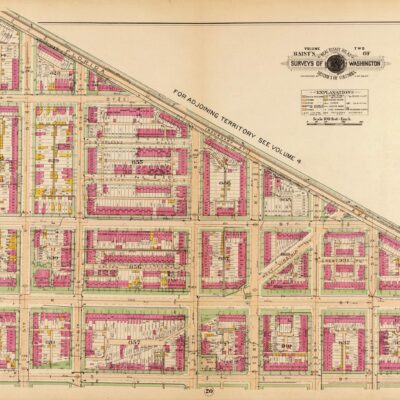

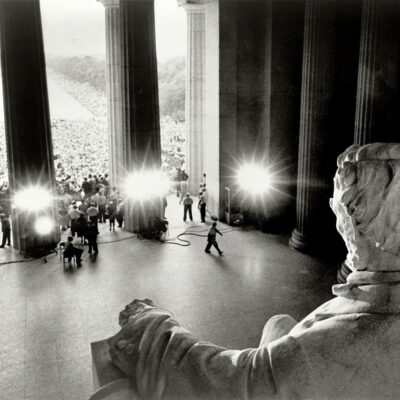

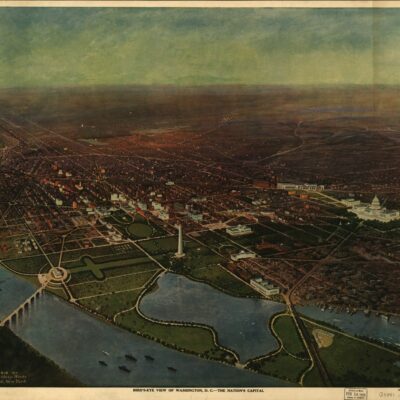

Paul J McDuff, 19, of Bolling Air Force Base, was snatched from death as he swayed outside an iron railing more than 110 feet above the crowded corner of 14th st. and Pennsylvania ave. nw. in Post Square.

Cheers surged from the throats of those who had watched the policemen crawl inch by inch to the target of a thousand eyes for 25 terrifying minutes.

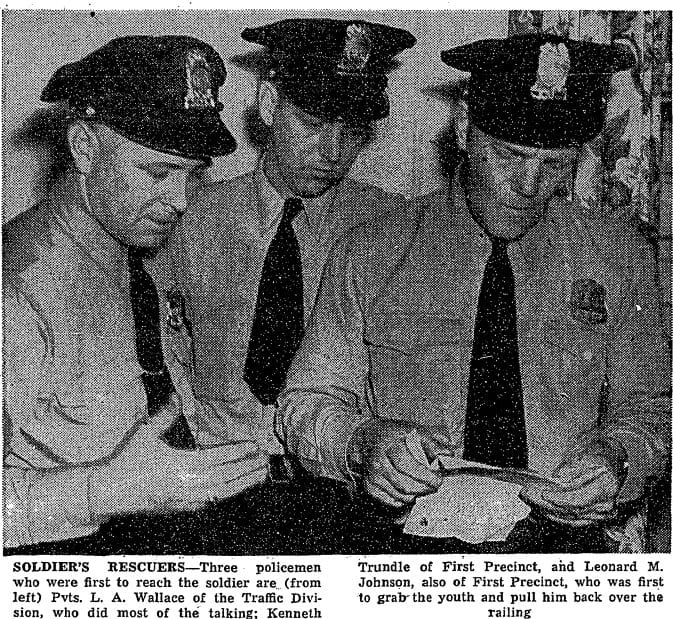

The heroes are Pvts. Leonard M. Johnson who threw the life-saving strangle hold on McDuff; L.. A. Wallace, who kept up a stream of rapid-fire reasoning, and Kenneth Trundel, who dragged him to safety.

The work of the policemen and Johnson’s final lunge at McDuff were termed by observers a miracle of coordination and split-second timing.

McDuff, knocked unconscious by the force of the blow which saved his life, was taken to Gallinger Hospital for observation.

He was confined in the locked psychiatric ward at Gallinger. He refused to answer questions and declined food. Though free to get out of bed and move around the ward, occupied by another mental patient, he remained in bed with his eyes closed most of the time.

McDuff crawled to the parapet through a ninth-floor window at the end of a short hall facing 14th street. He was not registered at the hotel.

On his hands and knees he crawled down the ledge until he reached the extreme edge of the corner racing the Capitol Dome. There he inched himself over the chest-high iro nrailing [sic] and stood high above the intersection holding to the fence with back-flung arms.

For a few minutes, pedestrians walked unconcerned up and down 14th st.; horns blew in the usual noise of the city.

…

Wallace stopped as soon he [sic] saw McDuff. Their eyes were approximately 15 feet aparts. McDuff’s eyes were crazed with a mixture of fear and confusion, and in a shaking voice told the officers he would make the plunge if they came any closer.

And then Wallace started talking. With sweat sprouting from his brow he kept talking for 25 minutes.

His first words: “Hey, Mac, Let’s talk it over. Come here a minute,” and for the first 14 minutes the officers stood their distance. In these minutes, a life hung in the balance. A false move could have sent the soldier plummeting to his death, and yet an untaken move meant more minutes in which his life could be lost. In these minutes Wallace was sizing up his opponent.

This is where the writer sensationalizes the story a little … eh, a lot … to pump up the drama. Also, it’s unclear how he was able to take down these words, verbatim.

His words, delivered with excitement, yet without panic, were taken down verbatim.

“Let’s talk it over, Mac. We got a lot to talk about.”

“There’s no sense in jumping, Mac. Think of all the people you’re going to hurt.”

“Just talk it over with me for two minutes, that’s all.”

“Don’t jump now, Mac. You’ve got your whole life to go.”

“Where’s you home, anyway, Bud? What’s your name?”

“Hey, son, that’s a long way down there. You’ve been in the Air Force. You know that’s a long way down there. Hey, son, don’t jump now. Take it easy.”

“Hey, Joe, have you got a cigarette? I want one bad, and I’m damned it I didn’t leave mine down there. Give me a cigarette, will you, Joe?”

Wallace wasn’t waiting for McDuff to answer, and the soldier spoke rarely, and then only in low mumbles. Once or twice he told the officers not to come closer or he would jump. Wallace, who remembered nothing of his conversations, interpreted one of these mumbles to mean “troubles.”

“You got troubles? Tell me your troubles, Mac. I got troubles. We all got ’em. You know that”.

“Come over here. We’ll see what’s wrong.”

At this point Wallace produced a bottle of whisky, which had come from the bar nine floors below.”

“Hey, Joe. Do you drink? Here’s a bottle. Let’s have a little drink. Just you and me.”

“What are your troubles, bud? Hey, what is your name anyway? Joe? It used to be Joe, when I was in the Army. Mac? Jim? Jack?”

During a pause in the monologue the officers ducked under one of the horizontal bars, perhaps two feet closer to McDuff. He said again he would jump if they came closer.

During the next few minutes, while maintaining a stream of conversatoin [sic], the officers ducked under successive bars until they were less than 10 feet and 2 bars from their man. There they waited.

Even though you know what happens, isn’t the suspense killing you? It’s like reality television, but no where near as horrible as Jersey Shore.

“Don’t you like the Army, Joe? We’ll get you out of the Army. We guarantee it, if you just come over here.”

“What would your mother think of you now,” Wallace asked.

“Me, I got no mother, but if I had I wouldn’t hurt her for anything in the world.”

“Hey, I’ll help you climb over that fence, son. Just come over here.”

A siren screamed as the Fire Department rushed to the scene with a big ladder, and a pitifully small canvas life net.

“Turn ’em off, turn ’em off,” an officer shouted on the ninth floor. “Those sirens will scare him into jumping.”

Wallace resumed his conversation with an invitation.

“Hey, Mac, how about coming home to my house for a nice friend chicken dinner?”

Above McDuff, a hotel employe had started lowering a rope from the floor above, to lasso the man to safety.

On the 14th st. side, another officer was crawling, apparently unnoticed, toward him.

Beneath McDuff, the Fire Department prepared to raise the ladder.

For a split second the ladder held his attention.

In that split second Johnson acted.

From a low crouch to pass underneath the last horizontal bar, the officer leaped. With a lunge he wrapped his right arm around McDuff’s neck, and bent the soldier back over the rail, to safety.

The crowd yelled, in relief and admiration, as the officers hauled McDuff through a window. He had been knocked unconscious by the force of Johnson’s grab. on the floor of the Smith suite, McDuff lay rigid, sweat streaming from his flushed face.

It was later discovered that McDuff had been recently transferred to Bolling Field and was despondent due to a complete reversal of fortunes in his military career.

The policemen were subsequently hailed as heroes are presented with awards for valor at a luncheon in August, held (of course) at the Willard Hotel.