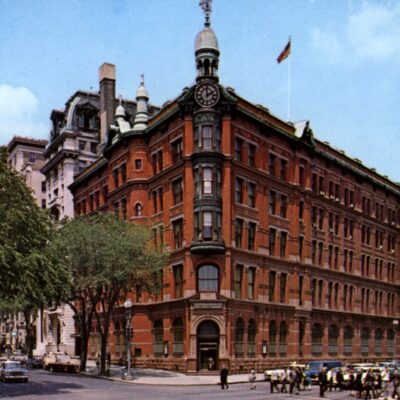

The Washington Monument, standing majestically in the heart of the nation’s capital, is a symbol of American pride and a tribute to its founding father, George Washington. However, the sleek, simple obelisk that we recognize today was not the original design. Robert Mills, the architect behind the monument, had initially conceived a far more ornate and elaborate vision for this national landmark.

Mills’ original design was grand in its detail, intended to be a testament to the nation’s reverence for its first president. The plan featured a colonnaded base, with a massive statue of George Washington in a chariot at its center, all of which would be topped by the familiar obelisk. While budget constraints and design modifications eventually led to the simpler structure we see today, Mills’ vision showcased the grandeur and ambition of early American architectural aspirations.

The transformation from the original design to the final structure is a fascinating journey through architectural evolution, economic challenges, and a nation’s quest to find the most fitting tribute to its beloved leader. It’s a testament to the ever-evolving nature of art and the compromises that often come with bringing a vision to life. One can only wonder how the D.C. skyline would have looked if Mills’ initial design had come to fruition.

Source: Library of Congress

In 1833, marking the centennial of George Washington’s birth, the Washington National Monument Society was formed. This group of dedicated citizens began fundraising, amassing over $28,000 by the mid-1830s. Their vision for the monument was clear: it should be “unparalleled in the world” and resonate with “the gratitude, liberality, and patriotism” of the American people. A competition for its design was announced, and architect Robert Mills emerged as the winner.

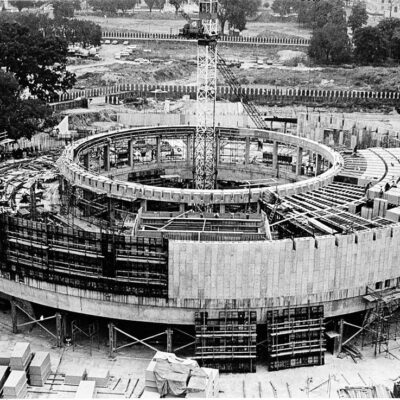

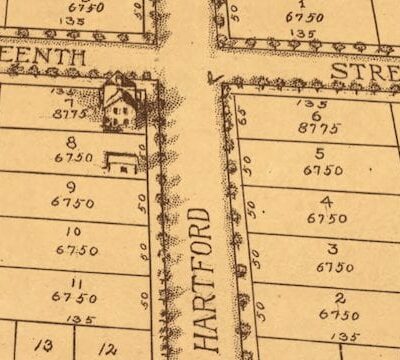

His initial vision was a grand 600-foot obelisk surrounded by a circular colonnade, topped with a depiction of Washington in a chariot and flanked by statues of 30 Revolutionary War heroes. However, the design’s complexity and its estimated cost of over a million dollars caused some hesitance. By 1848, the society decided to commence with the obelisk’s construction, hoping that its emerging presence would encourage more donations.

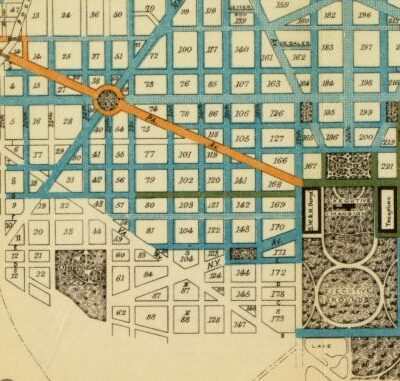

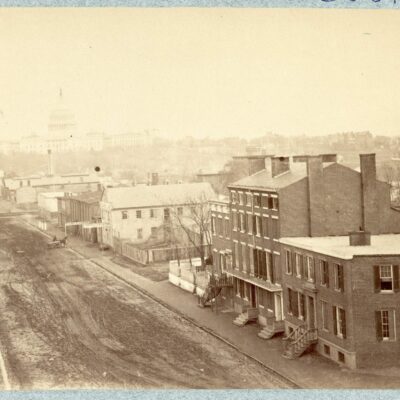

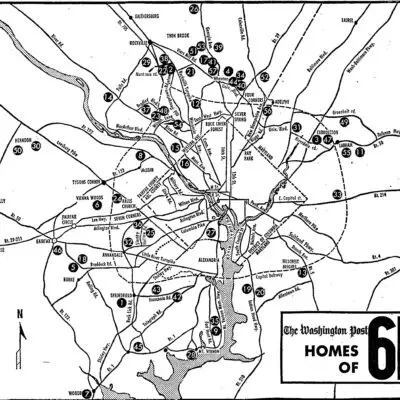

The chosen site for this landmark shifted from its original location. Congress provided 37 acres of land slightly south and east of the initial spot, chosen by L’Enfant, due to the original’s unstable ground. This new location promised panoramic views of the Potomac and ensured the monument’s visibility from various parts of the surrounding region, including Mount Vernon, the resting place of George Washington.

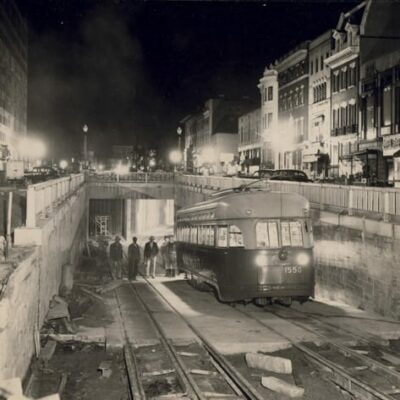

Construction officially began in the spring of 1848, marked by a grand Fourth of July ceremony. The nation’s reverence for Washington was evident in the speeches, praising his unmatched valor, wisdom, and leadership.

However, by 1854, the society’s funds were exhausted, and a subsequent Congressional appropriation of $200,000 was retracted due to political and societal controversies. One contentious practice was the society’s decision to incorporate memorial stones from various states, tribes, organizations, and even foreign entities. Many of these bore inscriptions that seemed out of place in a monument dedicated to Washington.

Tensions peaked when the “Know-Nothings”, an anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant party, allegedly stole and discarded a marble block donated by Pope Pius IX. They then took control of the society in a deceitful election, leading to Congress withdrawing its financial support. This group’s subsequent work on the monument was of such low quality that it was later discarded. Their diminishing public support and dwindling funds halted the construction for years, a pause that extended through the Civil War.