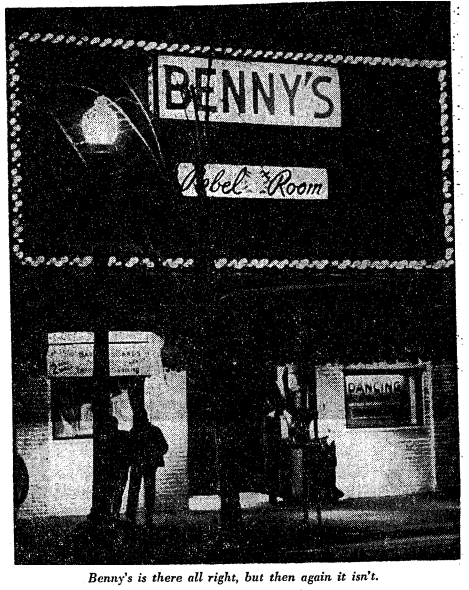

It was a few minutes before 3 a.m. on November 11, 1984, when the dancers assembled on stage at Benny’s Home of the Porno Stars for their final number.

As an X-rated movie flickered unnoticed on a screen in the back, the gyrating dancers stopped periodically to hug one another, pose for snapshots, or lean over a customer to have one last dollar bill tucked inside a black lace garter already bulging with cash. Benny’s, which billed its topless, bottomless show as “the most explicit on the East Coast,” was bumping and grinding its way to a halt, the latest casualty of the commercial gentrification of Washington’s once-booming porno district.

By daybreak, developer Jeffrey N. Cohen began pulling down the awning in front of the bar. Then more than 50 volunteers from the Franklin Square Association got busy clearing broken bottles from the curbside and painting plywood for a billboard reading “Franklin Square: Washington’s Next Great Neighborhood.”

The end was near for the 14th Street strip. And it had taken a coordinated campaign of legal challenges, private investigators, liquor license revocations, and millions of dollars in property acquisitions to make it happen.

When 14th Street Was Something Else

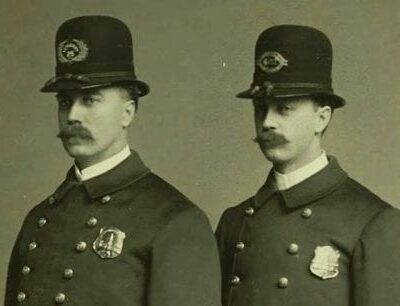

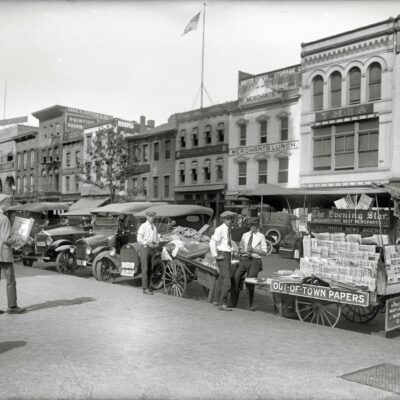

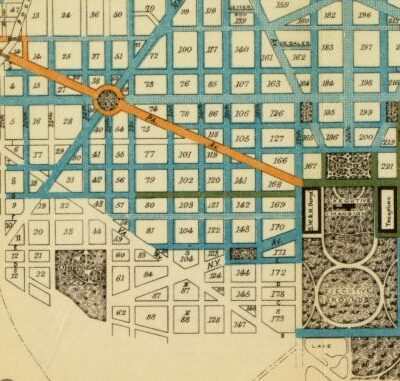

The 800 block of 14th Street NW wasn’t always Washington’s red-light district. In the 1950s, according to Thomas Lodge, a neighborhood resident since 1952, the top entertainers in the country performed there. The block evolved from high-class entertainment into “a kind of a place for soldiers on leave” during the Vietnam era, and then finally into a pornographic area in the 1970s.

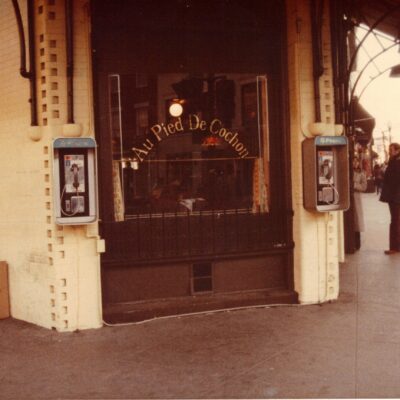

As late as November 1969, the Washington Post’s late-night dining guide listed the Californian Steak House at 1522 K Street NW as a legitimate restaurant serving “steaks, chops, Italian food and seafood, a la carte.” Benny’s Rebel Room offered a “honky-tonk piano and ragtime tunes.”

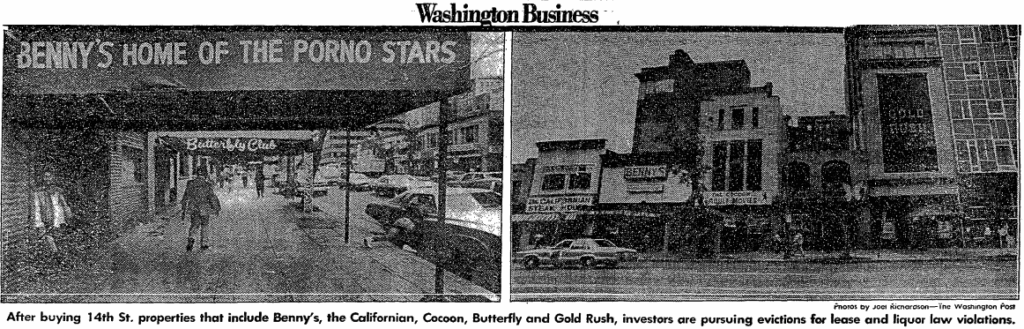

By 1982, that world had vanished. The block between H and I streets had transformed into what residents and police called the “combat zone.” In a cramped office at the Gold Rush bar, one owner in a three-piece suit leaned back in his chair and smiled: “A half-million dollars. It would take a half-million dollars to buy me out.”

He wasn’t far off.

The Law That Sat Dormant

In 1977, D.C. passed zoning regulations prohibiting “sexually oriented businesses” throughout the city except in high-density zones like downtown, and only with special permits. No such permits were ever granted. Existing establishments were grandfathered in but couldn’t expand.

For years, the city did little to enforce these rules. As Washington Post business writer Jerry Knight observed in October 1983, the very existence of the block was “as much a monument to free enterprise as a testament to free thinking.” The city found it easier to tolerate the strip in one contained area than to worry about dispersing the activity elsewhere.

But the downtown real estate boom was changing the calculation.

The Developer Who Bought the Block

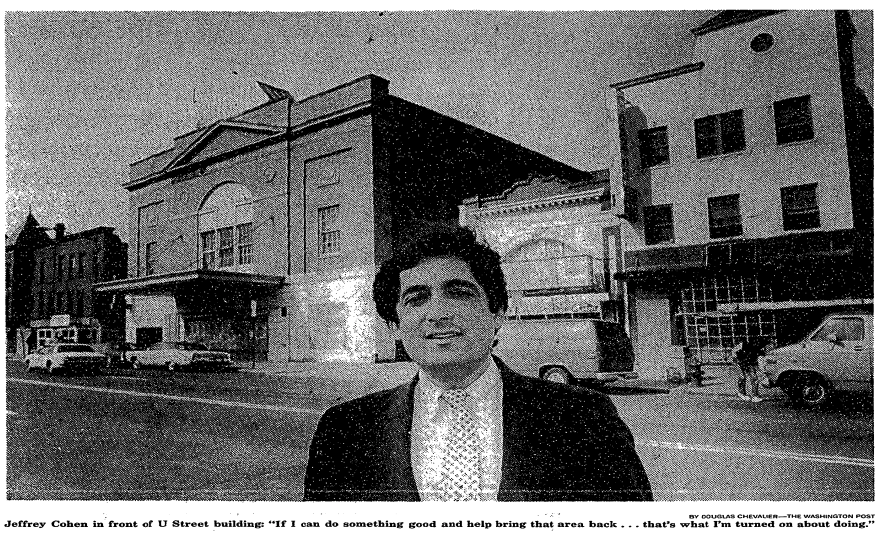

Jeffrey Cohen was 21 when he bought his first property in 1971 for $24,000 and flipped it for $36,000 six weeks later. By the early 1980s, he’d become one of Washington’s most aggressive developers.

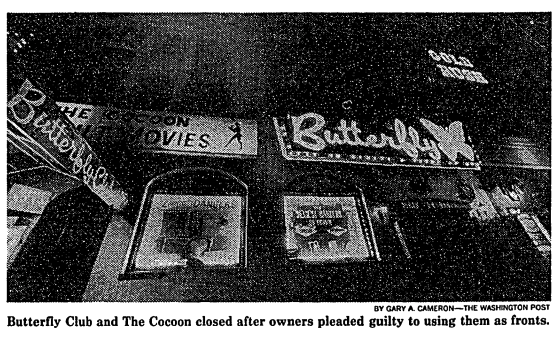

Starting in 1978, Cohen quietly purchased properties along the strip: the Parkside Hotel on I Street, then the buildings housing Benny’s, the Californian Steak House, The Cocoon, The Butterfly Club, and the Gold Rush. By 1985, he controlled what would become a $12.5 million deal.

His timing was perfect. The Franklin Square area was booming. The new Convention Center had opened blocks away. Metro Center station sat two blocks south. New office towers were rising near 11th and I streets. An estimated 1 million square feet of office space had been leased in the area in 1982 alone.

One thing stood in the way of further development: the strip.

The Franklin Square Association

In 1981, major downtown developers formed the Franklin Square Association with an $80,000 budget funded mainly by real estate interests. Their mission was to clean up the area’s seedy image.

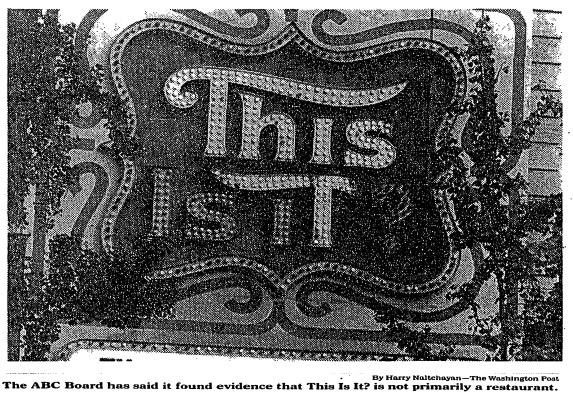

The campaign began in earnest in January 1984 when the association challenged liquor licenses for The Butterfly at 823 14th Street and This Is It? at 813 14th Street. They hired private investigators whose reports described sexually explicit performances. They submitted 34 letters from businesses claiming their employees were harassed by club barkers on the sidewalks.

The clubs fought back. Samuel Intrater, representing The Butterfly, argued that while the shows were sexually explicit, they weren’t “patently offensive” under community standards. In the This Is It? case, the club’s lawyer submitted 18 letters protesting harassment.

But the real breakthrough came with the Californian Steak House.

The Californian Falls

Jeffrey Cohen, who owned the building housing the Californian at 831 14th Street NW, complained to zoning officials that the establishment violated the 1977 regulations. The restaurant had converted to topless dancing but was operating under a restaurant certificate.

The case turned on whether naked dancing alone constituted “sexually oriented” activity. The owners’ lawyer argued that unclothed dancers weren’t sexually arousing unless they touched patrons.

The D.C. Board of Zoning Adjustment rejected this argument. In a “graphically worded 14-page ruling” issued November 22, 1983, the board concluded that “the positions assumed by the women and the manner in which the women displayed themselves are clearly designed to stimulate or arouse patrons.”

On December 2, 1983, in the first such action the city had ever taken, officials physically shut down the Californian. Police escorted Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs officials as they revoked the certificate of occupancy.

“We are absolutely pleased,” said William Cochran of Georgetown’s Advisory Neighborhood Commission. Community groups feared that if the Californian succeeded, sex shows would proliferate in their neighborhoods.

The Cascade

With precedent established, the dominoes fell quickly.

On July 18, 1984, the ABC Board denied This Is It?’s liquor license renewal. The board ruled the club didn’t operate as a bona fide restaurant, as required for a liquor license. It was the first time a topless club lost its license based primarily on sexual content.

The Butterfly Club and The Cocoon at 823-27 14th Street faced federal forfeiture after owners Abraham and Isidore Zaiderman of Potomac pleaded guilty to using the premises as fronts for prostitution.

El Ceazar’s Palace at 1016 14th Street closed when the landlord razed the building. The Golden Eagle at 1411 I Street voluntarily converted to a restaurant.

By November 1984, only Benny’s remained.

Benny’s Final Night

Owner Roger W. (Roddy) Simkins Jr. stood by the bar, shaking hands with regulars who stopped in to offer condolences. “This strip, for all intents and purposes, is already gone,” he said.

The next morning, Cohen pulled down the awning while Franklin Square Association volunteers painted the billboard proclaiming the neighborhood’s bright future.

James Bakalis, owner of the Gold Rush, was already weighing offers from developers.

Enter Trammell Crow

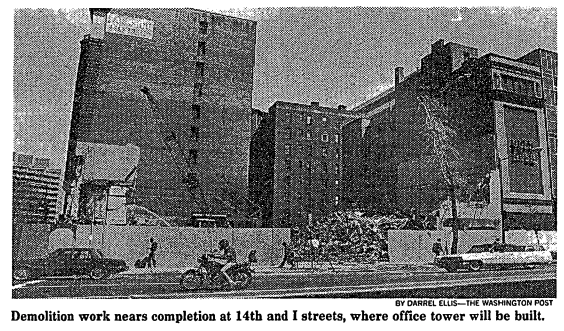

On April 2, 1985, the Washington Post announced that Trammell Crow Co., one of the nation’s largest developers, had purchased Cohen’s properties in a $12 million joint venture. The deal included the hotel, the boarded-up nightclubs, and plans for a major office building.

“This is significant because it represents Trammell Crow’s entry into the hottest real estate in the area,” said Arthur Schultz, the Franklin Square Association’s executive director. “They will bring an end to 14th Street as we know it.”

The irony was impossible to miss. Cohen had spent years as the crusading landlord fighting to evict his own tenants for moral violations. Now he was cashing out, selling the properties he’d cleaned up and pocketing millions in profit.

Demolition

By April 1986, Benny’s, the Californian, The Cocoon, and The Butterfly had been reduced to twisted steel and shattered bricks. Trammell Crow was clearing the site for a 12-story office tower.

Lt. Robert Poggi of the city’s prostitution task force explained the impact: “Our experience has been that sexually oriented businesses are fronts or contact places for prostitution. Without a concentration of adult clubs, potential customers won’t have the incentive to drive downtown.”

He noted that traffic jams had decreased, along with drug sales, drunk driving, and assaults associated with the area.

Arthur Schultz watched the demolition with satisfaction. “It is so gratifying to see this,” he said.

What It Meant

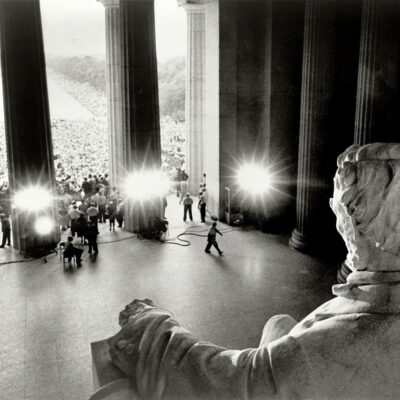

The transformation of 14th Street reveals how gentrification works when moral crusades and economic interests align. The Franklin Square Association presented itself as a community group concerned about quality of life. Many supporters genuinely were neighborhood residents worried about crime and prostitution.

But the $80,000 budget came from real estate developers who stood to profit enormously. The private investigators, legal challenges, and coordinated pressure on liquor licenses were all part of a strategy to clear valuable land for office development.

Jeffrey Cohen embodied this duality. His 1985 profile portrayed him as motivated by civic improvement: “If I can do something good and help bring that area back… that’s what I’m turned on about doing.” Yet he was simultaneously the landlord evicting tenants and the development partner cashing in on prime real estate.

The 1977 zoning law sat unused for years until developers needed it. Then it became the perfect tool: objective, legal, seemingly about community standards rather than profit.

Thomas Lodge captured the area’s evolution: “It kind of evolved from a good, high-class entertainment area, into a kind of a place for soldiers on leave, into a pornographic area.” By 1986, it was evolving again into office towers full of professionals.

The city never quite answered where the sex-oriented businesses, prostitutes, and drug dealers actually went. As Lt. Poggi noted, dispersal was the goal, not elimination.

Roger Simkins had the last word in 1986, delivered with wry perspective: “I think that certainly there were people who got their start there, one way or another. But I don’t think the city has lost anything.”

By then, the 14th Street strip was already rubble, ready for transformation into Washington’s “Next Great Neighborhood.” Whether the neighborhood was greater for everyone, or just for those who could afford the new office rents, was a question the bulldozers didn’t pause to answer.