Today’s post is a brief story covering the topic of the old Washington Redskins, today’s Washington Commanders and the political maneuvers leading to being the last NFL team to integrate. They finally did so in 1962 with three black players on their roster, including Bobby Mitchell. Thanks to GoDCer Jim for emailing this idea.

From Boston Braves to Washington Redskins: Early Days

In 1932, George Preston Marshall bought the Boston Braves football team with two partners. After a dismal first year with significant losses, his partners sold their shares to Marshall, making him the sole owner.He moved them the following year to Fenway Park and renamed them the Boston Redskins.

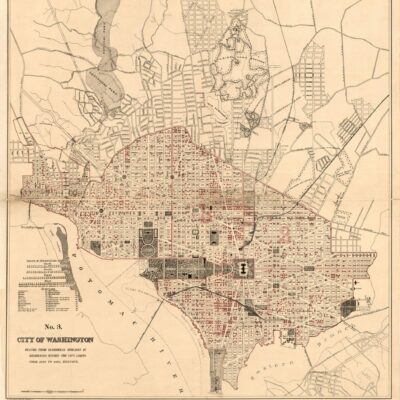

He eventually gave up on Massachusetts and moved the team to Washington in 1937 after lackluster fan support, despite playing in the the 1936 NFL Championship Game.

George Preston Marshall: A Deep Dive into His Background

Marshall grew up in West Virginia and moved to Washington as a teenager, where his father owned a newspaper. Later, his father’s laundromat business in the District expanded to 57 locations, which George took over and sold in 1946.

NFL’s Unspoken Ban on Black Players and the Break

Marshall was clearly a racist and unapologetic about that fact. In 1933, he informally organized a “gentleman’s agreement” to prevent any NFL team from signing black players. Marshall openly exhibited racism and made no apologies for it. In 1933, he informally set up a “gentleman’s agreement” barring NFL teams from signing black players. However, in 1946, due to political pressure in Los Angeles regarding a stadium lease at the Coliseum, the Rams signed local UCLA stars Kenny Washington and Woody Strode. Meanwhile, Cleveland signed Bill Willis and Marion Motley to the Browns’ roster.

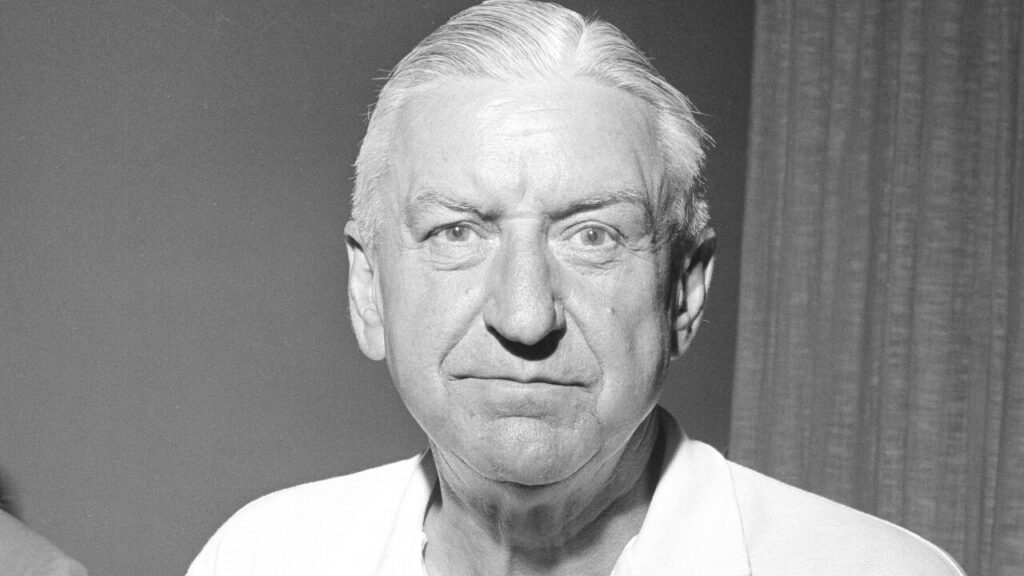

Marshall vs. Povich: A Legal Tussle

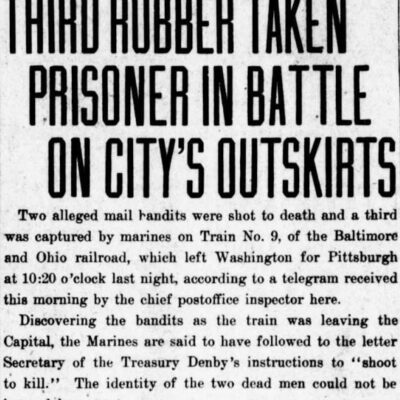

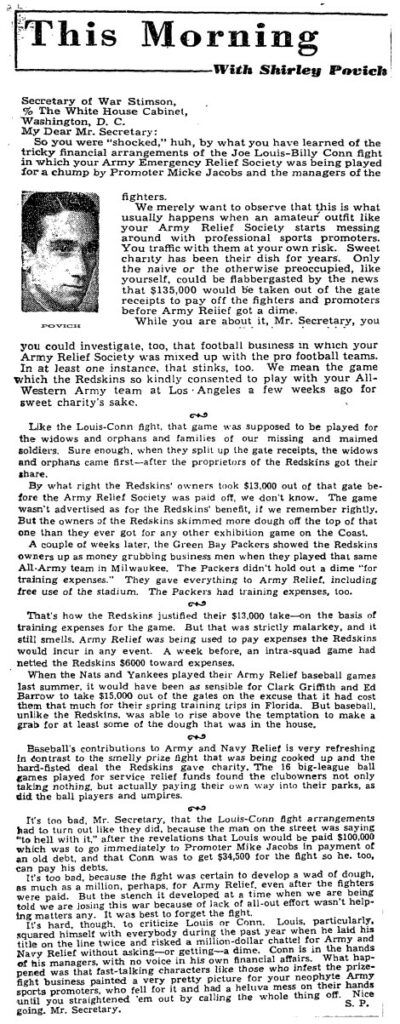

The Washington Post’s prominent sports journalist, Shirley Povich, took extreme umbrage to Marshall’s racist position and statement, regularly chastising him publicly in his columns. The frequency of his commentary was enough that Marshall files a lawsuit against Povich and the Post in 1942, suing them for libel with damages of $200,000 or $3.6 million in today’s money.

A copy of the actual article in question (from September 26, 1942), leading to the lawsuit it below, with some of it transcribed for easier reading.

[T]he game which the Redskins so kindly consented to play with your All-Western Army team at Los Angeles a few weeks ago for sweet charity’s sake.

Like the Louis-Conn fight, that game was supposed to be played for the widows and orphans and families of our missing and maimed solders. Sure enough, when they split up the gate receipts, the widows and orphans came first–after the proprietors of the Redskins got their share.

By what right the Redskins’ owners took $13,000 out of that gate before the Army Relief Society was paid off, we don’t know. The game wasn’t advertised as for the Redskins’ benefit, it we remember rightly.

…

That’s how the Redskins justified their $13,000 take–on the basis of training expenses for the game. But that was strictly malarkey, and it still smells. Army Relief was being used to pay expenses the Redskins would incur in any event. A week before, an intra-squad game had netted the Redskins $6000 toward expenses.

Marshall was furious, filed his lawsuit … and lost. On October 30 that same year, Povich stuck a proverbial middle finger up at his opponent with another “This Morning With Shirley Povich” column, taking a victory lap after having fended off the lawsuit with the jury ruling in less than 20 minutes against the plaintiff.

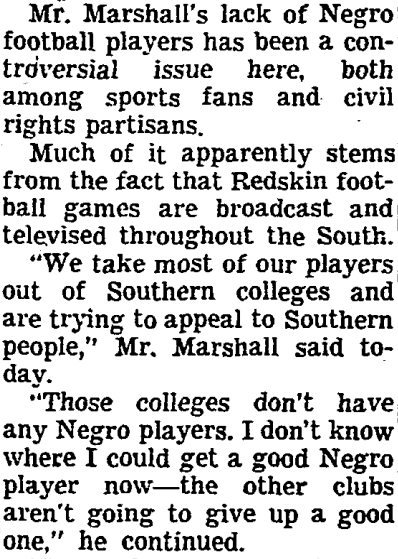

Marshall’s Controversial Statements About Integration

What journalist doesn’t love to pick at public personalities, politicians, socialites, or athletes. Povich loved attacking Marshall, and George made himself an easy target at times with his public comments, such as the one below.

We’ll start signing Negroes when the Harlem Globetrotters start signing whites.

George P. Marshall

The Redskins’ owner, Marshall, was openly a southern racist and resisted integrating his NFL team. But he also was a southern businessman who owned the southernmost football team. When he relocated the team to Washington in the 1930s, southern senators and congressmen often dominated the city. De facto segregation existed in most public facilities during the early part of the 20th century.

Marshall’s Southern Strategy

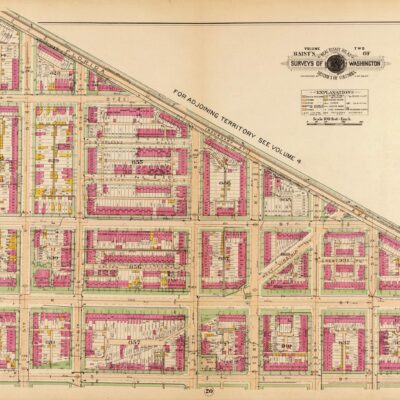

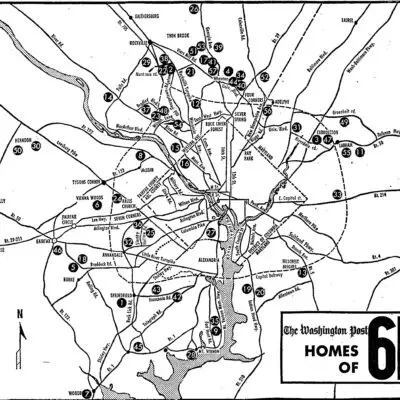

Marshall, the businessman, saw the team as something he could sell as entertainment to southern audiences hundreds of miles from the nation’s capital. He courted dozens of radio and television stations to broadcast Redskins games throughout the south and by the mid-1950s, 60 radio and 29 television stations were delivering play-by-play into living rooms across the south.

He constructed a vast business and, arguably, pioneered the first regionally promoted sports franchise in the U.S., expanding his market beyond the Washington region. The team showcased their skills in exhibition games across the south to cultivate a fan base. He also commissioned the “Hail to the Redskins” fight song, initially featuring the line “Fight for Old Dixie,” which they later changed to “Fight for Old D.C.”

It was a hugely profitable media venture for Marshall, and he was loath to give it up. So much so that his journalist nemesis Shirley Povich kept poking him in the press, including this “calling it like it is” column from December 125, 1959.

The Redskins have yet to draft, sign or otherwise acquire their first colored player despite the weekly episodes in which Negro athletes help give Marshall’s team an unhappy time. Unfortunately, they are incompatible with the decor Marshall has chosen for the Redskins, which is burgundy, gold and Caucasian.

The feeling is growing that Washington supporters of the Redskins are being scarified to the Southern television network to which Marshall is wedded. it is a 37-city link with most of the Souths big cities, the most profitable TV network in pro football. But for those Redskin fans who are not members of The White Citizens Council, it is too bad that too many good football players are ineligible for the Redskins from birth.

College football enjoyed immense popularity in the south. Marshall recruited many of his players from the top college teams. People continued pressing him on why his team wasn’t integrated. In a New York Times article by David Halberstam, he stated, “We recruit most of our players from Southern colleges to appeal to Southern audiences. Those colleges don’t have any Negro players.”

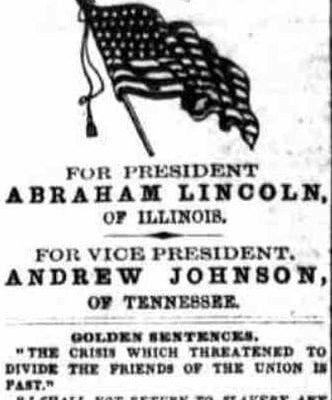

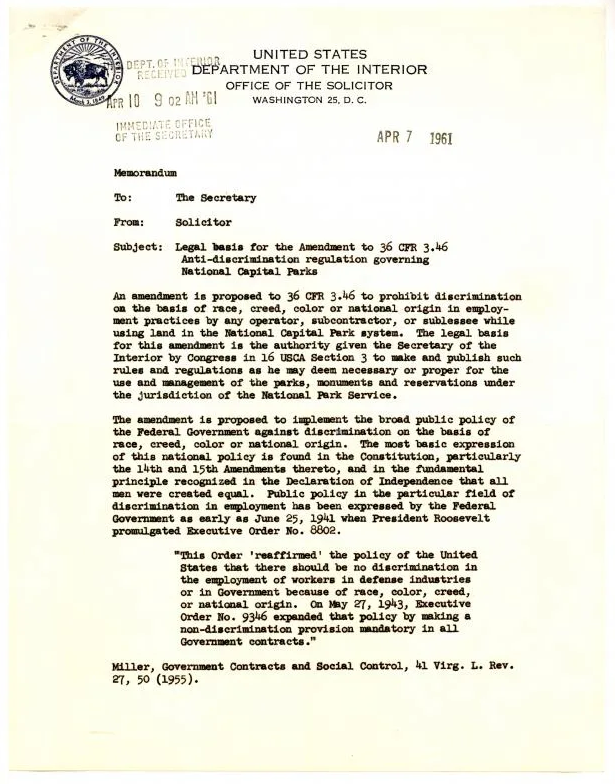

Pressure to Integrate: Kennedy Administration Steps In

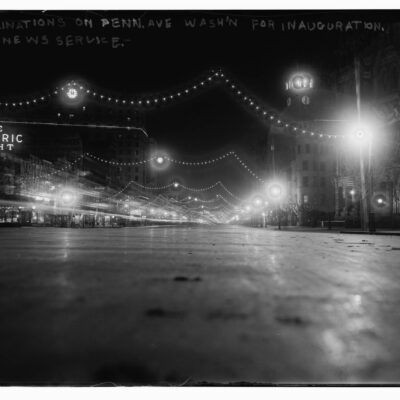

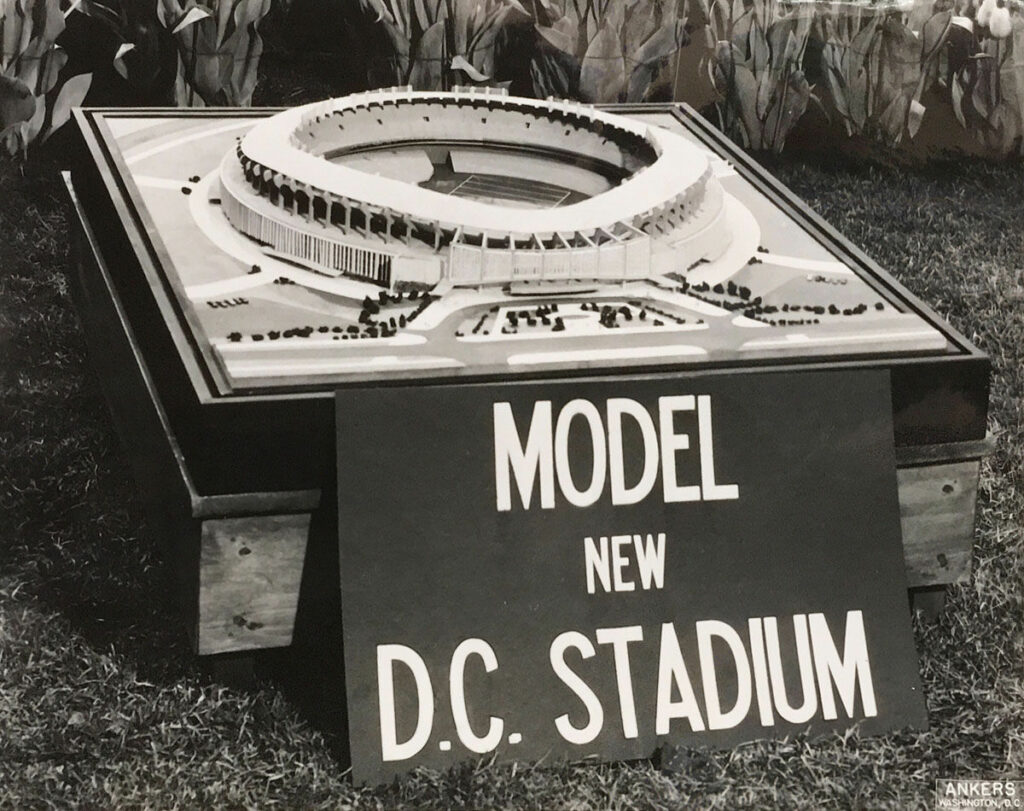

More important to note from the article is that Marshall’s Redskins were being heavily pressured by the new Kennedy Administration that their soon-to-deliver football stadium — DC Stadium and later renamed RFK Stadium — was being built on federal land as part of the National Capital Parks, under the legal jurisdiction of the Department of the Interior. The Secretary of the Interior was former Congressman Stewart Udall of Arizona (father of former Senator Tom Udall and Uncle of former Senator Mark Udall).

Secretary Udall issued a public ultimatum, mandating the integration of Washington’s football team as a condition of the lease for the new District of Columbia Stadium. He sent a letter to Marshall, warning him that the stadium “might not be available to the Redskins” in the fall should they not integrate the team. In addition, he attached an anti-discrimination amendment to rules governing the use of national parks.

1962: The Year of Integration for the Washington Redskins

Marshall held his ground and still didn’t field a black player in 1961, the first year of the the new DC Stadium. But, it was disastrous season for the Redskins on the field, ensuring they had the first pick in the following year’s new player draft. Prior to that, Marshall had been pushed by the NFL’s commissioner Pete Rozelle to concede that he would integrate the team with their upcoming draft picks.

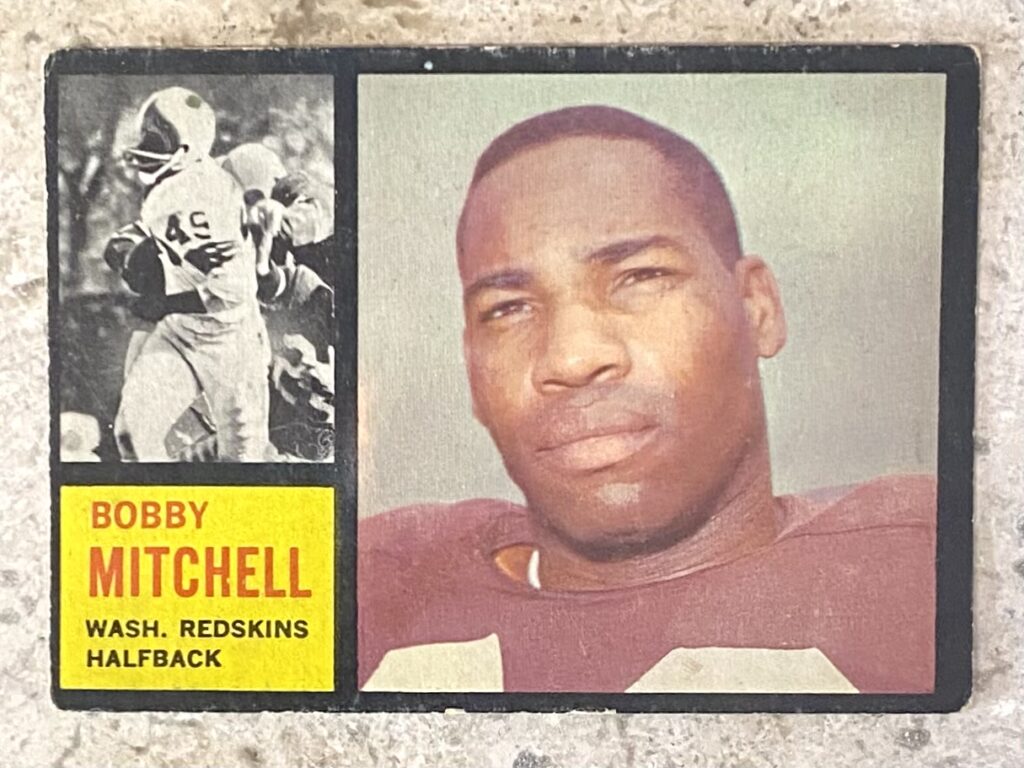

With their pick, they drafted Syracuse University’s Ernie Davis, who won the Heisman that year. Davis wanted to part of the Redskins, and more specifically Marshall. He was quickly traded to the Cleveland Browns for Bobby Mitchell and Leroy Jackson. Ron Hatcher was actually the first black player to sign a contract with the Redskins, but not the first to take the field. John Nisby would round out the first four African-Americans to play on the Washington football team in 1962.

A tragic note about this story is that Ernie Davis never played a down in professional football as he was diagnosed with cancer the same year he was drafted and died shortly thereafter. There’s a movie made about his story which you can watch on YouTube.

There is a great book about this which we recommend. It’s called Fight for Old DC: George Preston Marshall, the Integration of the Washington Redskins, and the Rise of a New NFL by Andrew O’Toole.