This is a guest post by GoDCer from Poolesville, Jack (the guy that tipped us off to some great stories, like the decapitated convict).

President Dwight Eisenhower’s inauguration was just five days away. For days the advance guard of a huge crowd had been streaming into Washington. In the days before commercial air travel had become popular, many travelers chose the train.

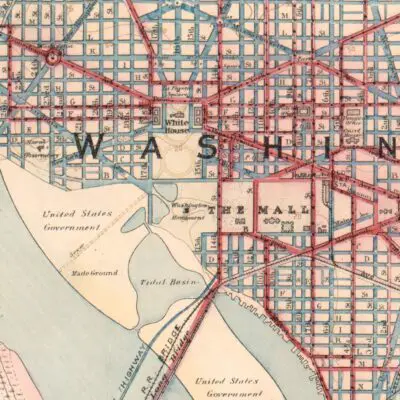

Union Station was already crowded on the morning of Jan 15th, 1953. The cathedral-like structure had opened on January 7th, 1907 and at the height of World War II seventy million passengers passed through its portals each year; at the time the Baltimore & Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Southern Railroads all serviced Washington.

John Feeney, 45 years old of Kensington, was at work in the Trainmasters office. He had worked at Union Station since he was a teenager. His job was to supervise all control tower operators and ensure safe operations of all passenger trains entering and leaving Washington.

Out at C Tower Harry Ball had just come on duty and was expecting a busy day routing trains at their first interchange track.

Further up the track, Harry Brower had control of Pennsylvania’s Federal Express. It was a crack express passenger train that had begun its journey in Boston the night before. The train was led by an electric locomotive that drew its power from overhead lines. Engineer Brower had taken control of the train at New York.

After leaving Baltimore, Brower saw nothing but green signals which were indicators that he could proceed as fast as the speed limit allowed. His train barreled through the Maryland countryside at speeds up to 80 mph. Two miles from Washington he saw a signal that ordered him to slow down and to begin the approach to Union Station. Brower applied the air brakes but little happened. The train was now traveling at about 65 mph as it hurtled underneath New York Avenue. Engineer Brower was now certain that his train was out of control. He yelled to the fireman to begin sounding the whistle to warn whatever was ahead. In 1953 trains did not yet have two-way radios.

To make matters worse the last few miles before the station were on a slight downgrade. As the Federal Express blew past C Tower Harry Ball recognized that a disaster was imminent. He could not divert the runaway train because it took three minutes to line up the necessary switching equipment. He picked up the telephone and called John Feeney in “K” Tower who was just a mile away. He shouted, “173 (The Federal Express) is running away!” The train was on track 16 which could not have been a worse choice. Track 16 was in center of the boarding tracks and Feeney knew that the platforms and concourse would be full of people at that hour.

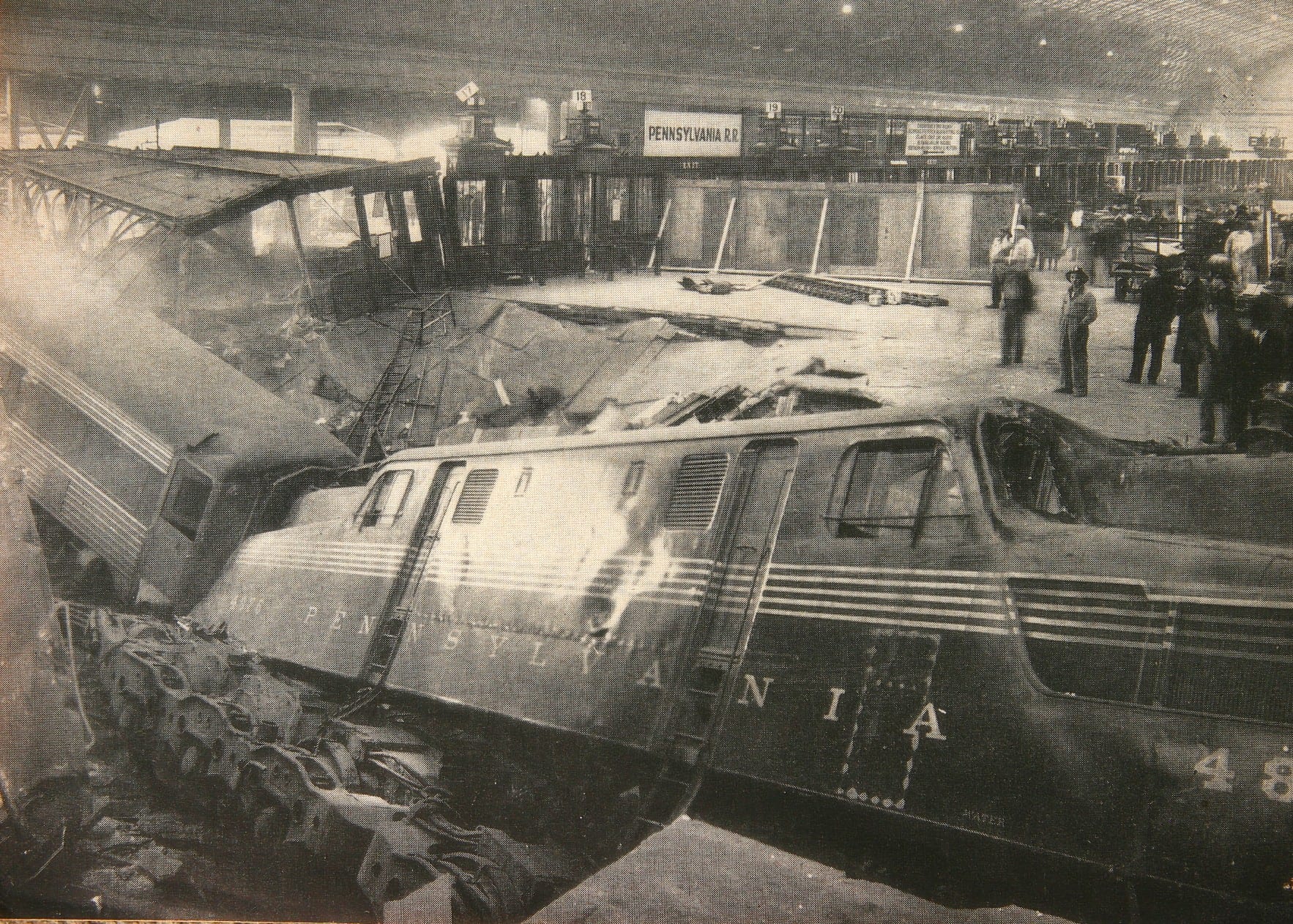

He then phoned the stationmasters office and shouted that everyone should evacuate. Somehow, miraculously, everyone in the office ran out, and waiting passengers ran from the concourse. The train sped down the boarding track and at about 40mph struck the bumper, crashed through the gates, destroyed a newsstand, and went through the concourse floor into the basement.

What happened next is best described in the coverage by the Washington Post.

For hair-raising seconds yesterday a runaway railroad train attempted to test the old physics class poser of the irresistible object.

The brakeless Pennsylvania Railroad engine and 16 cars and coaches didn’t prove themselves an irresistible force but they turned the immovable Union Station concourse into a shambles.

The powerful electric locomotive heading the procession weight 447,000 pounds, or 228 tons, according to railroad officials The cars behind it weighed at least 1000 tons.

The tearing power of this juggernaut brushed aside the track-end safety bumper, a sturdy device of steel I-beams. It tossed aside the iron grille track gate, hurling pieces throughout the concourse ceiling, smashed a newsstand, and destroyed part of the stationmaster’s office.

The ponderous engine furrowed across the cement concourse floor supported from below by steel columns. Part of the way across the concourse the floor gave way and the locomotive and two stainless steel coaches plunged to the floor below.

As was the custom of the time, doctors and nurses were rushed to the scene as well as every available ambulance. Incredibly, there were no fatalities but 87 people were injured.

Station officials had a huge problem on their hands. There was a gaping hole in their concourse, a train was sticking out of the hole, and the inauguration was just days away. Tens of thousands of visitors would be descending on the station shortly. The creative and improvised solution was nothing short of remarkable.

The two coaches were dragged out of the hole and the locomotive was lowered into the basement. A temporary wooden floor was erected over the hole and by the next day passengers were walking over the planking. After the inauguration the locomotive was extracted from the basement of the station.

Engineer Brower, no worse for wear, was back at work in a few days piloting the same train from Washington to Boston.

Eventually the Interstate Commerce Commission determined that a device that was supposed to supply air to the brake line was defective and thus caused the train to lose its brakes. The engineer was held faultless.

Reference material; Washington Post, Interstate Commerce Commission report 3497-A, Trains Magazine, August, 1953