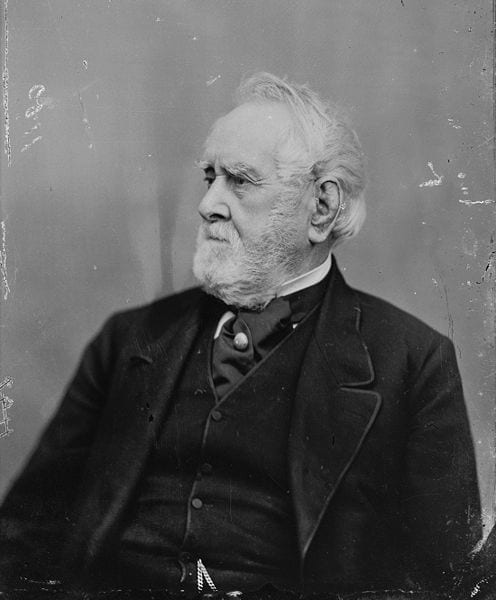

That claim might come as a shock to you, but the city’s most famous and wealthy resident of the 19th century, William Corcoran was asked his opinion about Georgetown’s prospects had the city of Washington not been placed right next to it.

Below is an interesting article that we dug up a special correspondence from the New York Daily Graphic in the Baltimore Sun, published on February 5th, 1874. Corcoran answered the writer’s question, in addition to giving a great description of the area from his youth.

I lately had a talk with the banker, Mr. W. W. Corcoran, about Georgetown, D.C., matters in general. Mr. Corcoran has given this city a gallery of art, a cemetery, a widows’ home, and prepared a park and endowed a college. He is the richest citizen we ever possessed, and his father was an Irish mechanic.

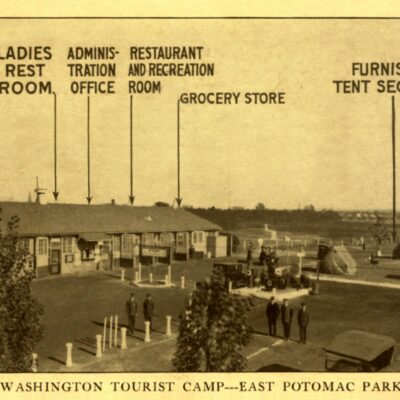

He was born in his father’s house seventy-five years ago, on Bridge street above High, Georgetown, and said that his father had built this house as soon after he settled in the place in 1787. The house was still in his possession. The business of old Georgetown was nearly all done below the bank, and the Union Hotel had no equal in the United States in its day. Rufus King and other rich men had a private table there, and for their common parlor, separate bedrooms, fire, and service paid a price then unheard of, and much denounced for its extravagance of six dollars a day per man, which was precisely their pay as Congressmen. John Randolph stopped there, and Georgetown did nearly all the business of the District of Columbia down to 1816-17.

I asked Mr. Corcoran what he thought would now be the rank of Georgetown as port and city had the capital not been placed beside it.

“Oh,” he said, “it would have been a great deal larger. It was nearly equal to Baltimore when my father arrived, and had some of the shrewdest Scotch merchant in the country. There were three or four large tobacco warehouses, and one of them was built nearly as far up Rock Creek as P Street Bridge. It was the tobacco raised in those days which made our neighboring country so poor, as it was not the habit to put any fertilizer on the land.”

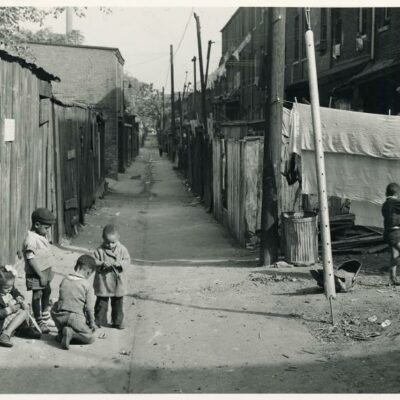

Mr. Corcoran said that one row of houses above High street long went by the name of “Scotch Row,” and a young man with him whom he called Mackay said that there were houses out High street which would not bring $800 now at sale that formerly rented for $800 a year. When the country trade cam in that way six cents a pound was the highest price asked for mountain venison in the early part of the century. Bladensburg never had any character of importance in Mr. Corcoran’s life.

He remembered Mason’s Island when General John Mason was in his prime. The frame house which stood there was burnt about 1804. The succeeding house was not remarkably spacious, but quite hospitable, and Mrs. Mason had the most beautiful garden, covering nearly the whole interior side of the island; and her gardener wrote a book on his craft, which was published in Georgetown. Here were born the five children of John Mason. The elder, John, was sent abroad to be educated, was put in the care of Lafayette, and for some time lived at La Grange with his father’s friend. He was fond of pleasure, however, and died early, after being secretary to Mexico with Mr. Poinsett. The second son was James M. Mason, afterward United States Senator and insurgent commissioner to Great Britain, who married Miss Chew, of Germantown, Pa. One of his daughters married the Confederate Adjutant General Cooper; another, Mr. —, of Baltimore, and a third, the insurgent Admiral Lee. General Mason’s estate stretched along the south bank of the Potomac as far as Little Falls. The old ferry house opposite the foot of High street, which is still standing in a delapidate [sic] condition, marks the celebrated ferry which Mason leased out, with its large flat boat propeled [sic] by sweeps. the causeway connecting the island with the Virginia shore was at times used by everybody en route to the ferry. This was the only great ferry of its period between the South and the North. General Mason was a democrat of positive type, the son of George Mason, of Gunston, and Mr. Corcoran compared Mason’s influence with the Tayloes, who were severe federalists. General Mason was buried about three miles back of Alexandria, on the road to Fairfax. He would have been a man of national fame had he lived anywhere but the District of Columbia.

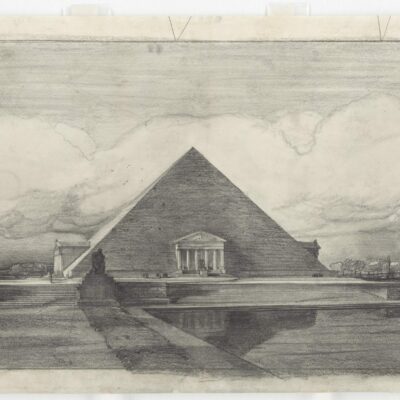

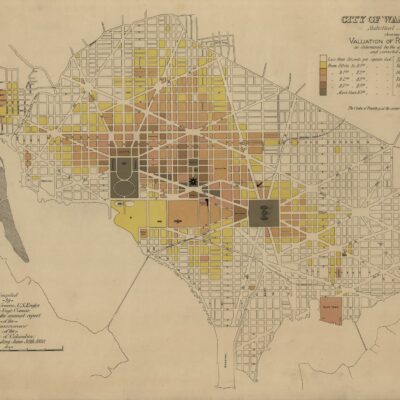

I asked Mr. Corcoran if he did not miss his familiar paintings at home. “No,” he said; “my sight is so bad that I can neither read nor look at pictures, and must take my enjoyment by what other people say.” He eulogized L’Enfant’s disposition of the almost unmanageable swamp which was selected for the site of Washington city, and spoke of the tulip, magnolia, gum and alder trees which grew along the Tiber and Slash run. Major L’Enfant, the plotter of Washington city, he often saw, and described him with precision. He wore a blue military surtout, buttoned close to the throat, and a tail, black stokc, but no shirt whatever. His hair was greased in the fashion of the times, and shone, and his head was covered with a large bell-crowned hat. He was a great walker, and carried a stick of several pounds weight which was truly formidable. Hewas moody, revolved what he thought to be his injuries, and would speak to very few persons. Mr. Corcoran presumed he was Catholic, on account of his intimacy with the Digges family. Christian Hinds, a local author, now aged ninety, had made a mistake when he wrote that L’Enfant commanded Fort Washington in 1813; he did reside there with the Digges family, but had no command. He died north of the city, on Digges place, without a public funeral or any manifestation, quite poor and old. Mr. Corcoran had always meditated raising the body to give it honorable sepulture at Oak Hill cemetery.

![Army Officers at New Year reception, [Washington, D.C.], 1/1/25](https://ghostsofdc.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2014/01/26557u-400x400.jpg)