Have you ever wondered, “when was the Air and Space Museum built?” Join us on a historical journey to uncover the origins and construction timeline of this iconic Smithsonian institution on the National Mall.

Origins of the Smithsonian’s Aviation Collection

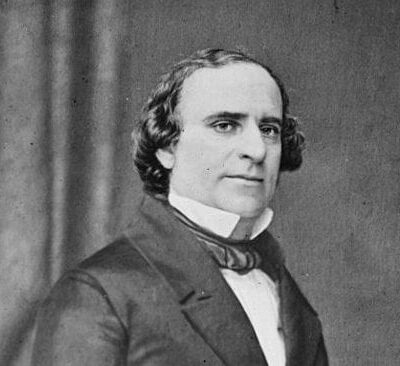

The Smithsonian’s connection to aviation dates back to the Institute’s earliest days under the leadership of its first Secretary, physicist Joseph Henry. Henry had a keen interest in flight and ballooning. In 1861, Joseph Henry invited aeronaut Thaddeus Lowe to fly a hot air balloon on the Smithsonian grounds. This marked a pivotal moment in American aviation history.

The establishment of the Smithsonian’s aeronautical artifact collection well before the chartering of the National Air and Space Museum in 1946 was not a coincidence. The beginnings of this collection can be traced to 1876 when the Smithsonian acquired its first flight-related objects: a grouping of twenty beautiful kites gifted by the Chinese Imperial Commission.

During World War I, the nascent aviation collection was moved into a temporary Quonset hut constructed behind the Smithsonian Castle. Nicknamed the “Tin Shed,” this humble structure publicly opened in 1920 to display the Institution’s aircraft acquisitions. But it only provided limited exhibition space as the collection continued expanding rapidly.

Visionaries like Joseph Henry set the Smithsonian on a course intertwined with the history of flight in the 19th century, although Congress did not formally establish the National Air Museum until 1946. These treasures resided in the Tin Shed, Arts and Industries Building, and external storage spaces until they could be consolidated in one magnificent museum.

Early Plans and Designs for the National Air Museum

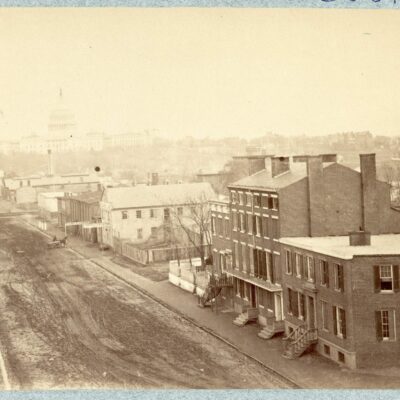

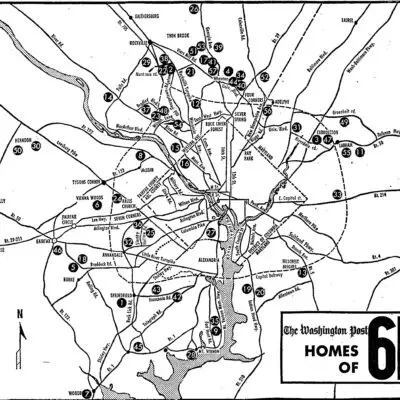

Shortly after Congress chartered it in 1946, the National Air Museum earnestly searched for a site to build a dedicated museum. In a 1947 meeting, the Advisory Board unanimously chose Washington DC for its accessibility to visitors.

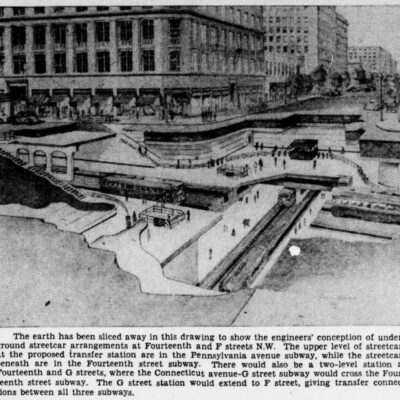

In 1948, the Smithsonian commissioned the Public Buildings Administration to conduct a preliminary study analyzing potential sites for the museum’s construction. Locations including Arlington Farms and Theodore Roosevelt Island were under consideration. By 1949, the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) and Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) were advising the Smithsonian on selecting an ideal site. Sites along Independence Avenue near the National Mall were recommended by these agencies.

Pursuing Excellence: The Smithsonian’s Quest for the ‘World’s Finest’ Aviation Museum

After securing the site between Fourth and Seventh Streets on Independence Avenue in 1958, the Smithsonian looked to commission an architect who could design a National Air Museum worthy of the Institution’s lofty aspirations. As a 1948 Washington Post article relayed, the Smithsonian firmly believed this proposed museum could become the “world’s finest” once built.

According to a subsequent New York Times piece in 1954, the lack of exhibition space was already apparent, with many artifacts “lying in crates and packing cases in a nearby hangar.” It was evident that only a new grand building on the National Mall could appropriately showcase what was described as “the world’s finest aviation collection.”

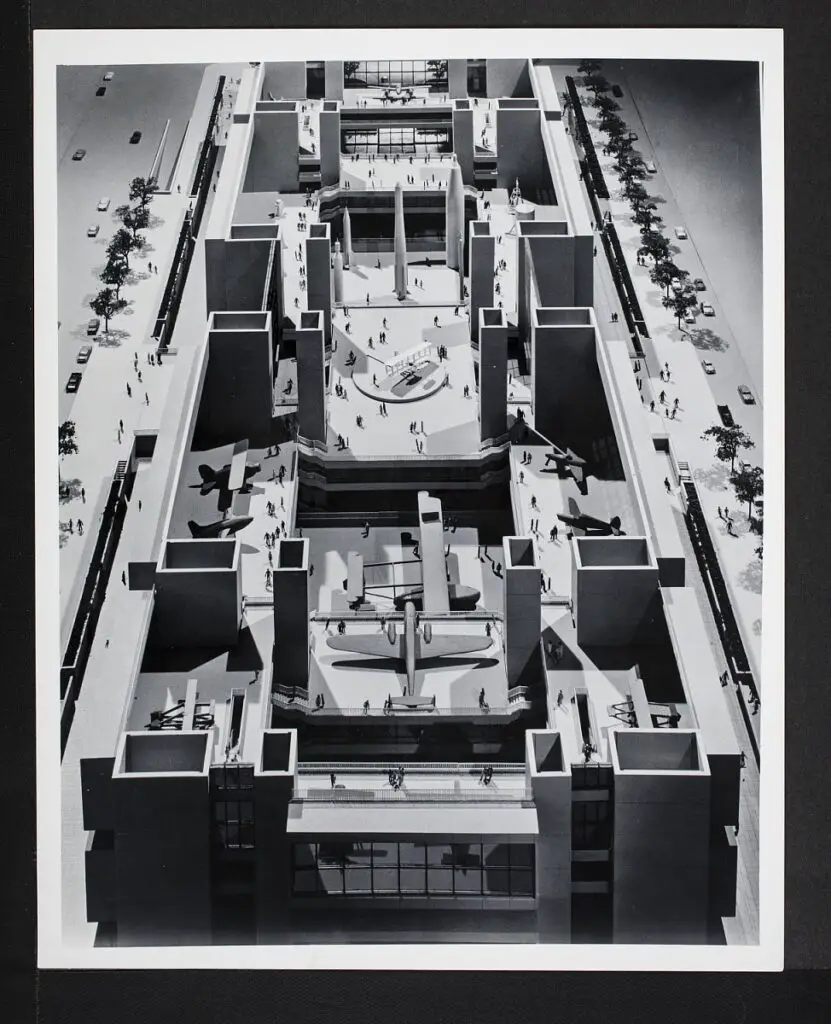

With the site confirmed, the Smithsonian restarted planning efforts, developing exhibit mockups and massing studies in 1962 that conveyed the desired scale and grandeur for the museum. But the critical piece – legislation authorizing funds to commence an architectural design competition – remained elusive.

Selecting an Architectural Visionary to Design the National Air and Space Museum

After over 15 years of deliberating on the museum’s location and purpose, the process could finally begin in 1963 to select an architectural firm to design the facilities. Congress finally appropriated $500,000 to fund a design competition, a hard-won victory after over a decade of advocacy by Smithsonian leadership. The Institution worked with the General Services Administration to solicit proposals from prominent architecture firms. The Smithsonian conferred with the General Services Administration, which at the time managed federal building projects, to initiate a formal architect selection process.

The GSA provided a list of acceptable candidates that the Smithsonian evaluated, ultimately narrowing it down to three prospects: Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum (HOK) of St. Louis, Skidmore Owings & Merrill (SOM) of Chicago, and Eero Saarinen and Associates of Connecticut.

To aid with the critical decision, the Smithsonian enlisted local architecture firm Chatelain, Gauger & Nolan to assess each potential team. Their report concluded that because this was the first major aviation museum, there were no existing precedents to follow.

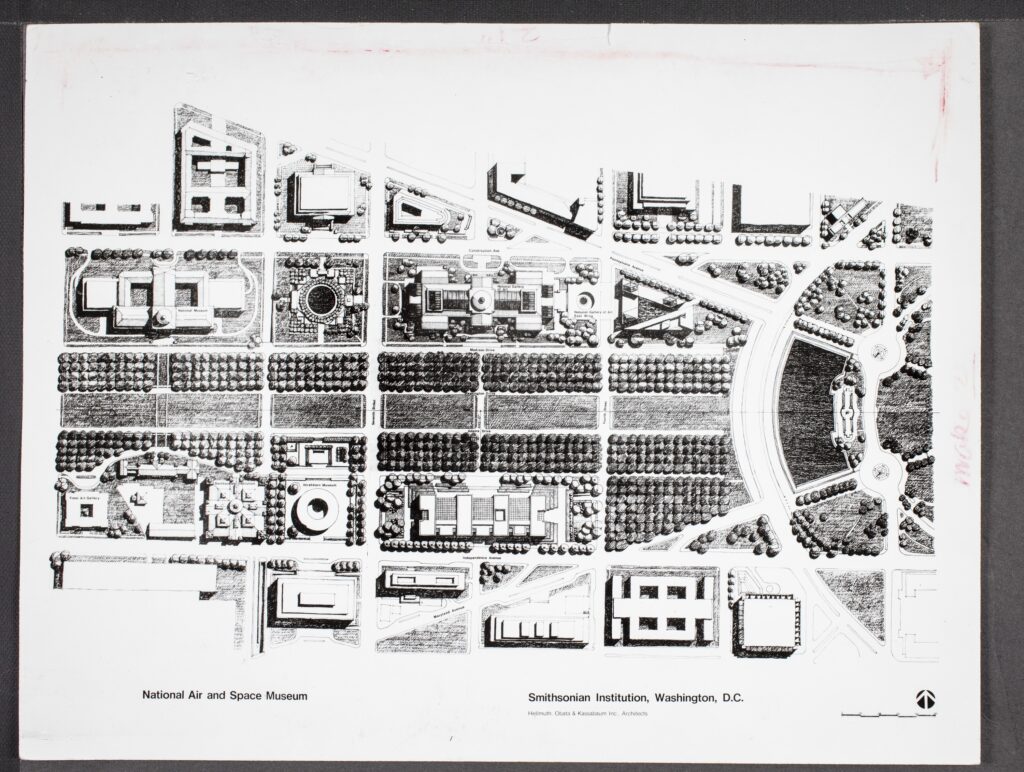

In September 1963, the Smithsonian’s Board of Regents unanimously selected HOK as the principal architect and landscape designer. The Regents appointed local firm Mills, Petticord & Mills as associate architects.

HOK Principal Gyo Obata faced the immense challenge of crafting a modern museum that also complemented the neoclassical context of the National Mall. After years of false starts, the critical task of designing a facility worthy of housing the Smithsonian’s treasures could finally commence. The Smithsonian dreamed of creating the “world’s finest” aviation museum, and Obata boldly set out to meet this ambitious goal.

Overcoming Obstacles to Finally Open the National Air and Space Museum

With agency approvals secured in 1964, the Smithsonian intended to break ground in 1966 and open in 1969. But the escalating Vietnam War stalled Congressional appropriations, halting progress.

Despite re-securing funding in 1971, costs had ballooned from $40 million to $60-$70 million. HOK redesigned a smaller museum to reduce the budget.

Obata’s new design measured 785 x 225 feet, similar to the National Gallery. It eliminated the horizontal roof overhang but maintained the modernist aesthetic. More wrangling on design details continued through 1972.

The National Capital Planning Commission urged using marble cladding to complement the Mall. But the architects argued concrete better expressed the building’s modernity. Approvals were finally granted to start construction in 1972 for a July 1976 opening date.

After years of obstacles, the Smithsonian could soon debut its long-awaited cultural treasure and open the doors to America’s “world class” aviation museum.

Legacy and Ongoing Evolution

In 1973, Congress fully appropriated construction funds, and on November 20, 1972, the construction team broke ground on the National Mall site after overcoming two decades of setbacks and false starts. The architects and construction team worked rapidly, completing NASM’s construction two years ahead of America’s Bicentennial in 1976.

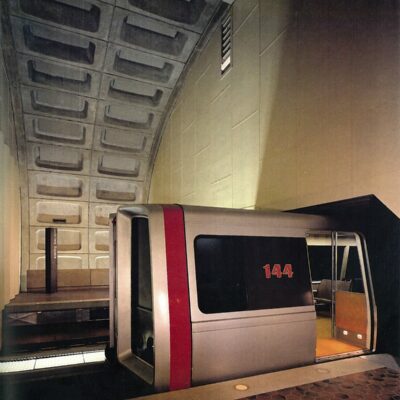

Source: National Air and Space Museum

Source: National Air and Space Museum

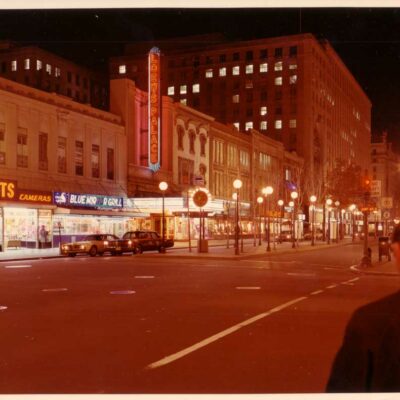

The public opening ceremony for the National Air and Space Museum was held on July 1, 1976 (view footage on C-SPAN). After enduring years of delays, budget cuts, value engineering, and criticism of its design, the museum finally became a reality. Rising on Independence Avenue, filled with historic aircraft and spacecraft, NASM quickly became a premier cultural institution.

Since its opening in 1976, the National Air and Space Museum has continued evolving through additions and renovations.