Many women at the outbreak of the Civil War did not know how to support their favored side. The roles of woman at the time were limited and none of them were direct involvement in the war. Though the true number is likely much higher, we know of at least 400 women who disguised themselves as men to join the troops. Some were following brothers or husbands, others in search of adventure, or out of patriotism. We know them because of their memoirs, or being found out when wounded or killed in battle. For some of them, we have both the true name and their masculine alias, and others just the one their fellow soldiers knew them by before they died on the field.

More than a century past, we are still finding out about some. In the 1990s, a stash of letters was remembered in an old attic in New York. They were letters home from a soldier fighting with the 153rd New York Volunteer Infantry. The Wakeman family lore told of a grandmother, still living after the war, mentioning a sibling who fought under the name Lyons Wakeman, but not much more was mentioned. The letters were from a Sarah Rosetta Wakeman. It wasn’t until the 1970s that the connection was made. To the Wakeman family, the secret was known that Rosetta had joined the Union under the name Lyons in the disguise of a man. To the rest of the world, Lyons Wakeman was simply a soldier who died during the war and is buried under the military headstone 4066 in Chalmette National Cemetery in New Orleans.

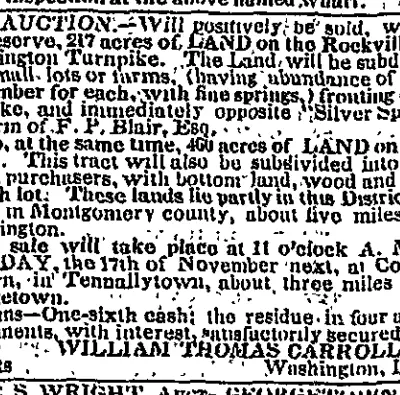

Rosetta was the eldest daughter of a large farming family in New York. As she grew older, the family grew more in debt. Thinking it the best way to serve the family, she left home and struck out in the guise of man to earn a living. Jobs that were open to women, such as laundress, did not pay the wages she needed to help support the family. She began work as a boatman on a canal when she met recruiters for the 153rd NY Volunteers. They told her she could earn a $152 bounty, think of it as a signing bonus, and $13 a month pay. She enlisted on August 30, 1862 as a private and sent some of the bounty home, telling the family to buy clothes and food.

To protect her identity, she had her family mail the letters address only to R.L. Wakeman. However, she signed them Rosetta, even saying that her family need not worry what they say in the letters as they are read by no one but herself.

She does not talk much about her reasons for leaving other than helping her father pay his debts. Nor does she talk much about the war as a whole, though she often asks her family their thoughts. She does at one point mention that she thinks the war will continue because the officers are making a pretty penny with their salaries. If they were to receive her pay of $13 a month it would be over already.

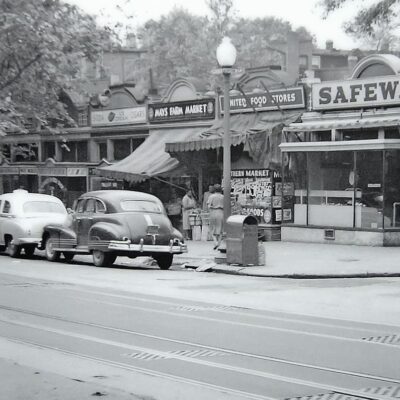

The first post for the 153rd was Alexandria, Virginia as guards for the defense of Washington. They were here just under a year when the New York Draft Riots happened. President Lincoln needed more men and so Congress passed a draft. The middle and lower class workers of New York rebelled against this act – think Gangs of New York. Fearful the same thing would happen during Draft Week in Washington, Rosetta’s troops were brought into the city and stationed on Capitol Hill.

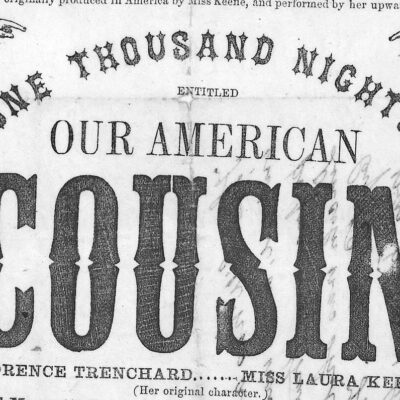

Here Rosetta described the job that her company performed. On a rotating schedule, they guarded Carroll Prison, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Depot, City Hall where the draftees were registered, the city and the camp. From August to October 1863 she was at Carroll Prison every other day. Carroll Prison was used as the Capitol Building decades earlier and has been subsequently called the Old Capitol Prison. She comments in a letter home about three women held there. One was a Confederate Major who had ridden once into battle with her men, the other two held as spies were likely famous Southern spy Belle Boyd and a Rebel mail carrier that Belle named as Ida P.

During their time in Washington, the 153rd practiced drills just as any regular regiment. Rosetta claimed she had “got so I can drill just as well as any man there is in my regiment.”

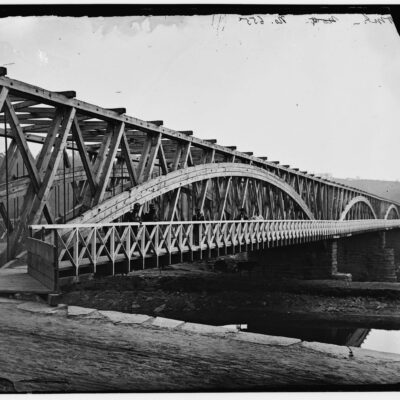

In February 1864, her regiment was given marching orders South to Louisiana. After fighting at the Red River campaign and a 70-mile forced march after, Rosetta was admitted to the hospital with chronic diarrhea where she died in May 1864. What seems such an unjust fate for soldier, it was the deadliest disease during the Civil War. The 153rd would a few months later return to Washington to defend against Confederate General Jubal Early’s attempted invasion and the review of the troops by President Andrew Johnson after the war.

If her letters home had not been preserved, historians would never know that Lyons Wakeman was truly a woman in disguise. How many other female soldiers are buried under their enlisted names or unmarked graves we will never know. What we do know is that there are many other women just like Rosetta Wakeman.

You can read the edited compilation of Rosetta’s letters in An Uncommon Soldier: The Civil War Letters of Sarah Rosetta Wakeman, Alias Private Lyons Wakeman, 153rd Regiment, New York State Volunteers, edited by Laura Cook

–This is an excerpt from Canden’s newest book to be released in March 2014: Wild Women of Washington, DC: A History of Disorderly Conduct from the Ladies of the District