This is a first guest post by new GoDC contributor Andrea Pawley, a resident of Washington, D.C. history.

Much of this post is based on Washington Arsenal Explosion: Civil War Disaster in the Capital by Brian Bergin, edited by Erin Bergin Vorheis (The History Press, 2012).

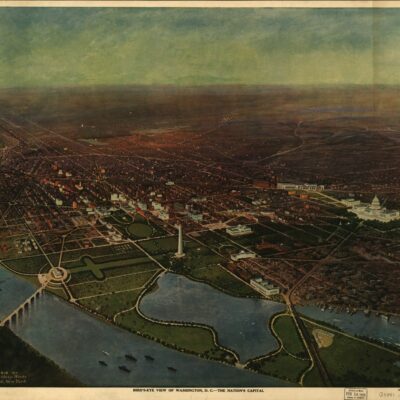

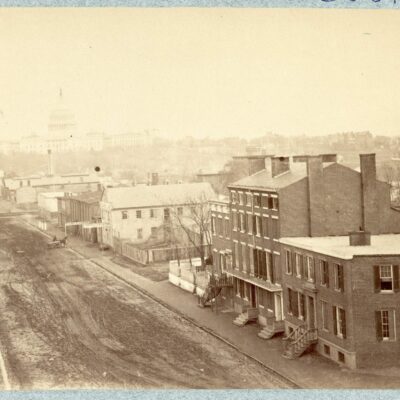

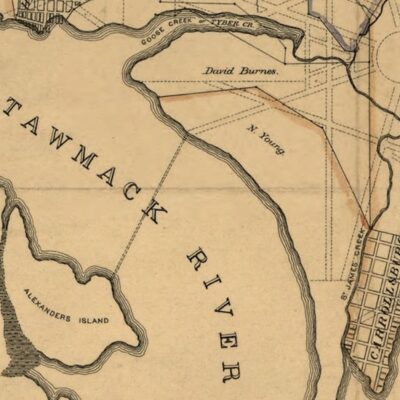

Friday, June 17th, 1864, was hot, especially for the women of the Washington Arsenal at the tip of what is now Fort McNair. Mothers and daughters, all of them from families poor enough to need the limited income generated by paid female labor at the time, sweltered beneath many layers of clothing topped by a hooped skirt. Over two dozen women and girls worked at the Arsenal’s laboratory making explosives used by Union soldiers fighting in the Civil War.

The women and girls who worked in the choking room at the laboratory weren’t allowed to talk, an activity considered by their superiors to be too distracting to their very precise effort. Fifty grains of gunpowder – no more, no less – filled each and every cartridge. The women sat together at long benches pulled up to a central table. For one person to get up from her seat, everyone on the bench had to move. Between the heat and the skirts and the silence and the benches, the choking room workers were trapped. Lunchtime, however, was a respite from these constraints, and that break approached.

Unbeknownst to the choking room workers or their supervisors, Arsenal Superintendent Thomas Brown had laid star flares out to dry nearby. He had done this many times in the previous months, but June 17th was a day hotter than most, possibly one of the hottest since the superintendent had found this new spot to dry fireworks to be used for July 4th celebrations. The tray that held the star flares lay only 35 feet from the choking room end of the laboratory. Just before noon, the flares began to explode. In a matter of seconds, incendiaries going off 35 feet from the choking room became flares shooting into the building. What happened next was the largest single-day tragedy in the history of Washington City to that time.

Explosions rocked the choking room. Fire consumed it. The tin roof was lifted from its wood and brick walls. Trapped by social circumstances on so many levels, most of the women and girls inside the laboratory died. Some passed away immediately, their lungs, clothing, and skin incinerated by super-heated gas. Others escaped the laboratory to die over the subsequent hours and days. In all, nineteen women and girls perished. The bodies of eight were burned beyond all recognition.

The survivors fled to their homes to be treated by relatives in the crude manner of the time’s medical treatments. Later that same day, both the Army and the District’s coroner conducted an investigation of the fire. Fault was found with the Superintendent and various lax practices. He faced no consequences that written history offers. The times allowed only for the most basic compensation of the injured and the families of the dead. A collection was taken up by the community to pay for the funeral, and many who perished were buried at Congressional Cemetery. The monument to the twenty-one women and girls who died still stands.