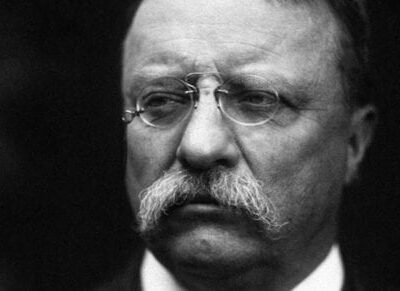

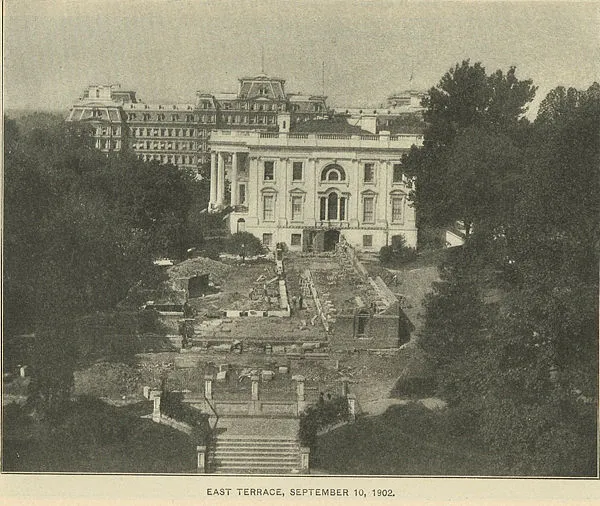

We suspect most White House visitors have walked through the East Wing entrance without realizing they’re standing where history’s most expensive presidential makeover is about to unfold. What started in 1902 as Theodore Roosevelt’s restoration of Thomas Jefferson’s vision for a simple east entrance—complete with cloakrooms for guests’ coats and hats—is now becoming the site of a quarter-billion-dollar ballroom. The same footprint that once welcomed “miners from Alaska, bankers from Wall Street or lumbermen from the piney woods of Maine” will soon host state dinners beneath crystal chandeliers.

On October 20, 2025, construction crews began demolishing part of the East Wing facade for President Trump’s $250 million ballroom project. This marks the first major structural change since President Truman’s extensive renovations in 1948.

Restoring Jefferson’s Democratic Vision

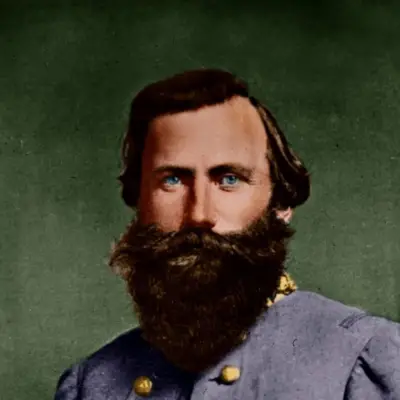

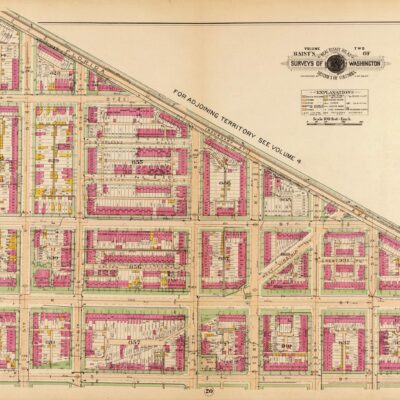

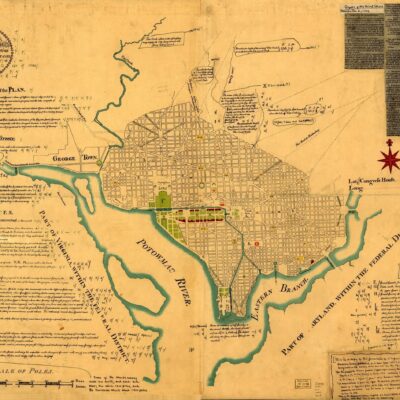

The East Wing’s story begins with Theodore Roosevelt’s ambitious 1902 White House renovation, but Roosevelt wasn’t creating something new. He was restoring Thomas Jefferson’s original concept. As The New York Times reported on September 15, 1902, the work aimed to “carry out the idea of Thomas Jefferson” by reopening “the old east driveway” and creating “the long colonnade wing on the east side of the building.”

Roosevelt’s renovation was part of a massive $550,000 improvement project designed with distinctly democratic ideals. The Brandon News of Mississippi reported on January 8, 1903, that the basement of the east wing was created as “what some might call a public-comfort building” with cloakrooms capable of handling “the wraps of 3000 people” during receptions.

The renovation solved a longstanding problem with White House entertaining. Before the restoration, public receptions meant “standing in rows three or four blocks long, for as many hours or more, often exposed to rain and snow,” according to The Brandon News. Roosevelt’s solution provided proper shelter and facilities while treating all guests with dignity, regardless of social status.

To sum it all up, those who appreciate the honor of the invitation which is extended the people at large to pay their respects to the head of the nation, will no longer be treated like a mob assembled on the street, but will be shown the courtesy that is accorded guests at any American home—whether they are miners from Alaska, bankers from Wall Street or lumbermen from the piney woods of Maine.

The approach and porte-cochere on the east cost $65,000 of the total project budget, reflecting the importance placed on creating a proper entrance that honored Jefferson’s architectural vision while serving practical needs.

Presidential Space Challenges Continue

Even after Roosevelt’s renovation, presidents continued struggling with space limitations. In 1914, President Woodrow Wilson demonstrated this ongoing challenge when he set up a tent in the White House garden. The Madisonian of Richmond, Kentucky, reported on May 26, 1914, that Wilson “pitched a headquarters tent in the old-fashioned flower garden lying just south of the one-story annex, which forms the east approach to the White House.”

Wilson’s makeshift office served his summer work needs because Washington’s heat made indoor work difficult. The newspaper noted that Wilson was “somewhat tired and has determined to do that which will overcome the tired feeling as much as possible” by working outdoors when practical.

The Wartime Transformation

The East Wing underwent its most significant structural change in 1942 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The Washington Post reported on May 1, 1942, that “An east wing is being added to the White House,” officially described as office space to “help relieve the present congestion in the White House.”

The public explanation was truthful but incomplete. The real purpose behind FDR’s expansion was to conceal construction of an underground presidential bunker during World War II. Secretary of the Treasury Morgenthau had insisted on the bomb shelter, though Roosevelt initially resisted the idea because he “felt that there was little chance of a German air raid,” according to reports that emerged in 1943.

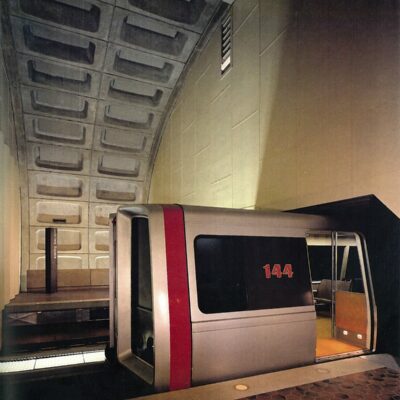

The expansion created the two-story East Wing structure that exists today, built directly over what became known as the Presidential Emergency Operations Center. The former cloakroom from Roosevelt’s era was converted into the White House Family Theater during this renovation.

Preserving History Amid Change

The East Wing has weathered preservation battles throughout its history. In 1925, The Washington Post reported on July 7 about R.T.H. Halsey from the Metropolitan Museum leading opposition to proposed White House changes. Halsey arrived for inspection of the executive mansion, highlighting ongoing tensions between those who wanted to preserve historical integrity and those pushing for modernization.

The 1925 article noted Roosevelt’s letter asking that changes “remain unmarked,” showing ongoing sensitivity about maintaining the White House’s historical character while meeting contemporary needs.

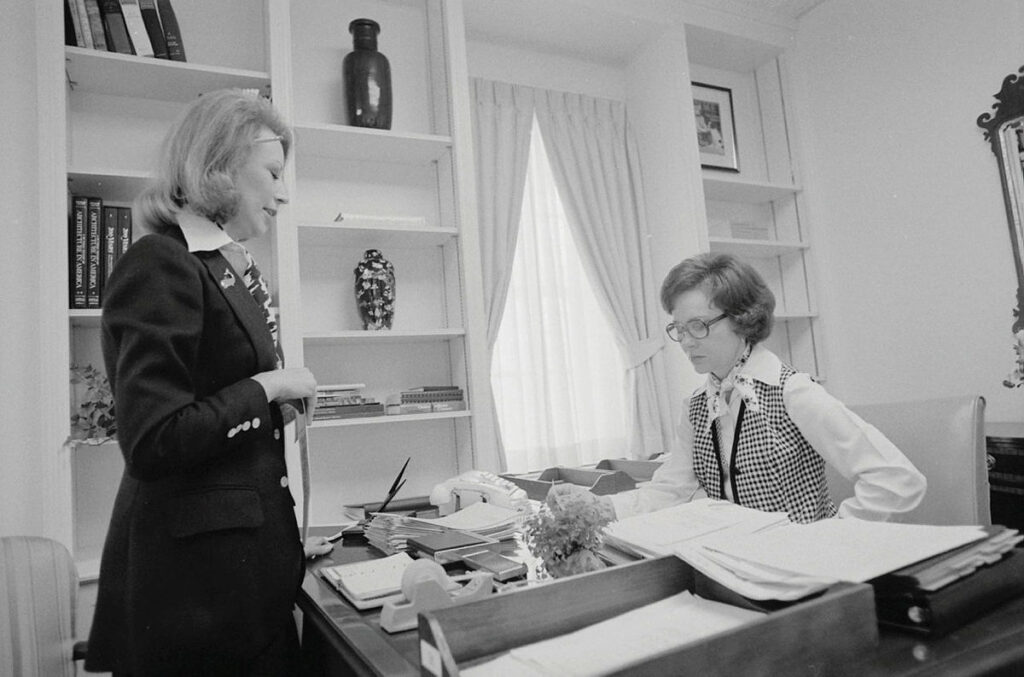

The First Lady’s Domain

Since 1977, the East Wing has served as the traditional base of operations for the first lady and her staff. The space houses the Social Secretary, the Graphics and Calligraphy Office that produces White House invitations, and serves as the main visitor entrance for foreign dignitaries. The wing also includes the White House theater and provides the route most tourists take when entering for public tours.

The Latest Chapter

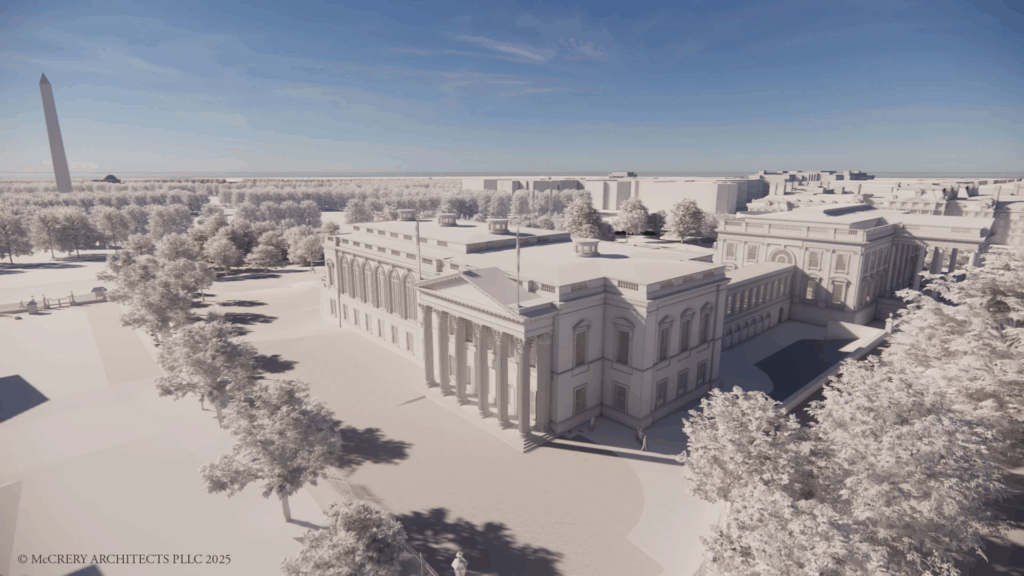

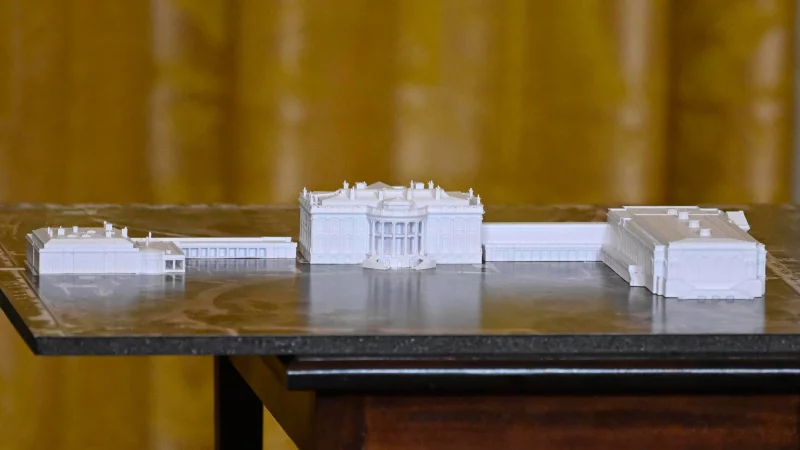

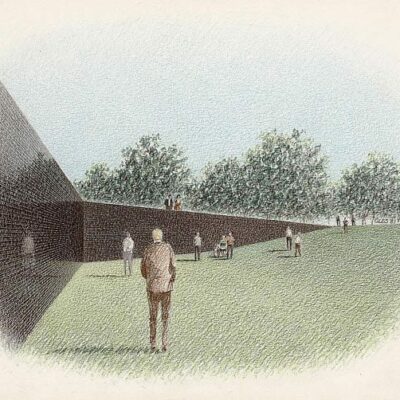

The current renovation represents the most dramatic change in the East Wing’s 123-year evolution. The new ballroom will span approximately 90,000 square feet with capacity for nearly 1,000 guests, featuring gilded design elements including crystal chandeliers, Corinthian columns, and marble floors.

The $250 million project is being privately funded and is expected to be completed before January 2029. During construction, East Wing offices will be temporarily relocated, and the wing will be modernized while maintaining what officials describe as the White House’s architectural heritage.

A Century of Adaptation

From Jefferson’s original vision to Roosevelt’s democratic restoration, Wilson’s practical tent solution, FDR’s wartime security needs, and now a formal ballroom, the East Wing site has continuously adapted to serve the changing requirements of the American presidency.

Each transformation reflects its era: Roosevelt’s emphasis on democratic access, Wilson’s informal pragmatism, FDR’s wartime necessities, and the current focus on formal diplomatic entertaining. The underlying challenge remains constant—how to balance the White House’s role as both a working government building and a symbol of American hospitality.

The East Wing’s evolution from simple cloakroom to golden ballroom tells the story of how presidential priorities, security needs, and entertaining expectations have changed over more than a century. As construction continues, visitors can still walk through the East Wing entrance, following the same path that has welcomed Americans and world leaders for generations, even as the space prepares for its most luxurious incarnation yet.