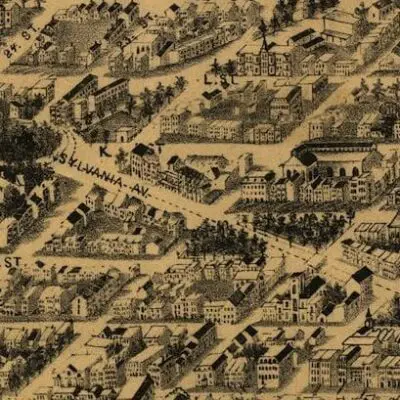

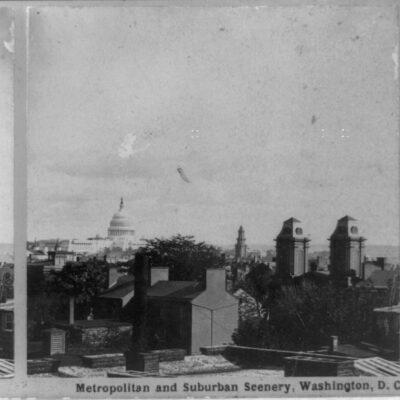

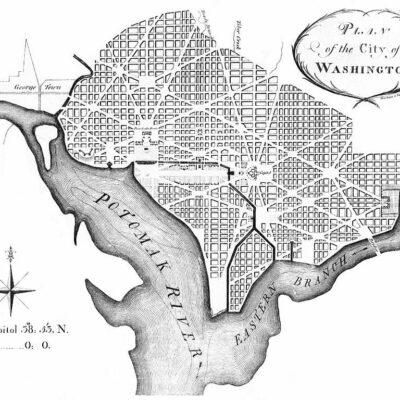

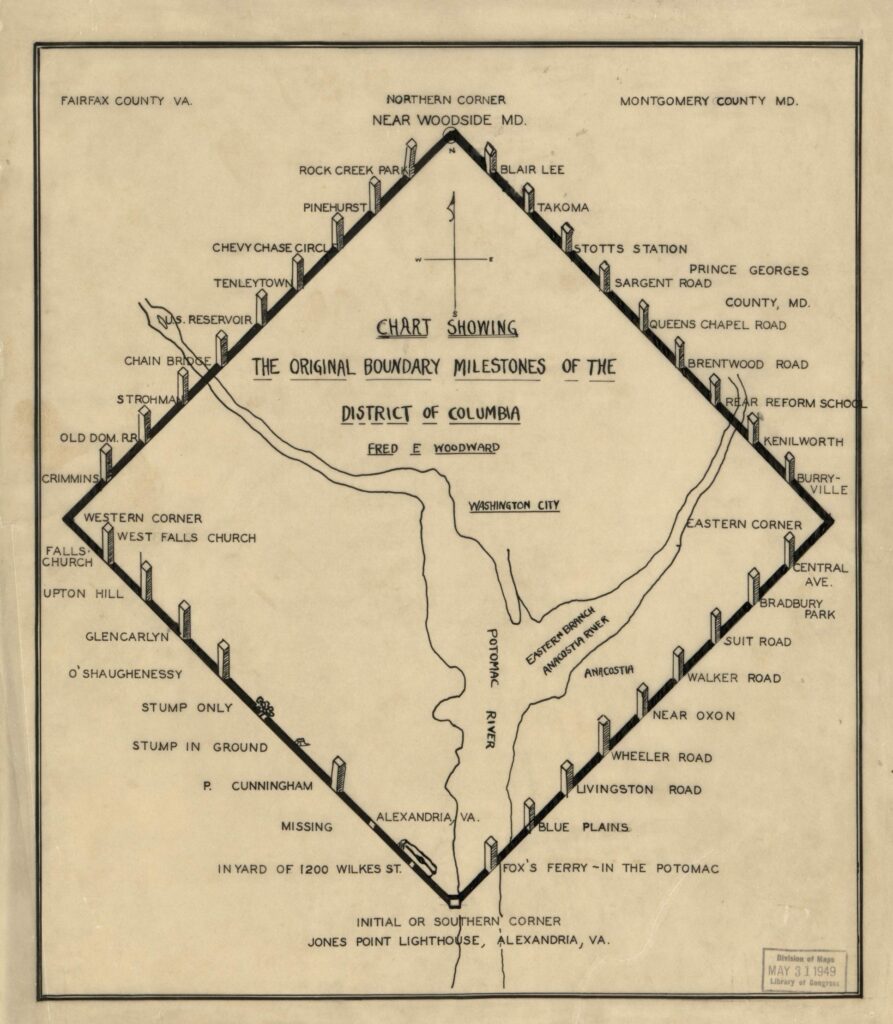

The borders of Washington D.C. have been a point of contention since the city’s founding. In 1791, the District of Columbia originally included the port cities of Alexandria and Georgetown along with the newly created capital city. But residents in Alexandria soon grew frustrated with how the District was governed from Washington.

In 1846, after decades of lobbying, the Virginia portion was “retroceded” back to the state, shrinking the District to just the area around Washington. For over 60 years Alexandria remained part of Virginia while the capital struggled to expand within its smaller borders.

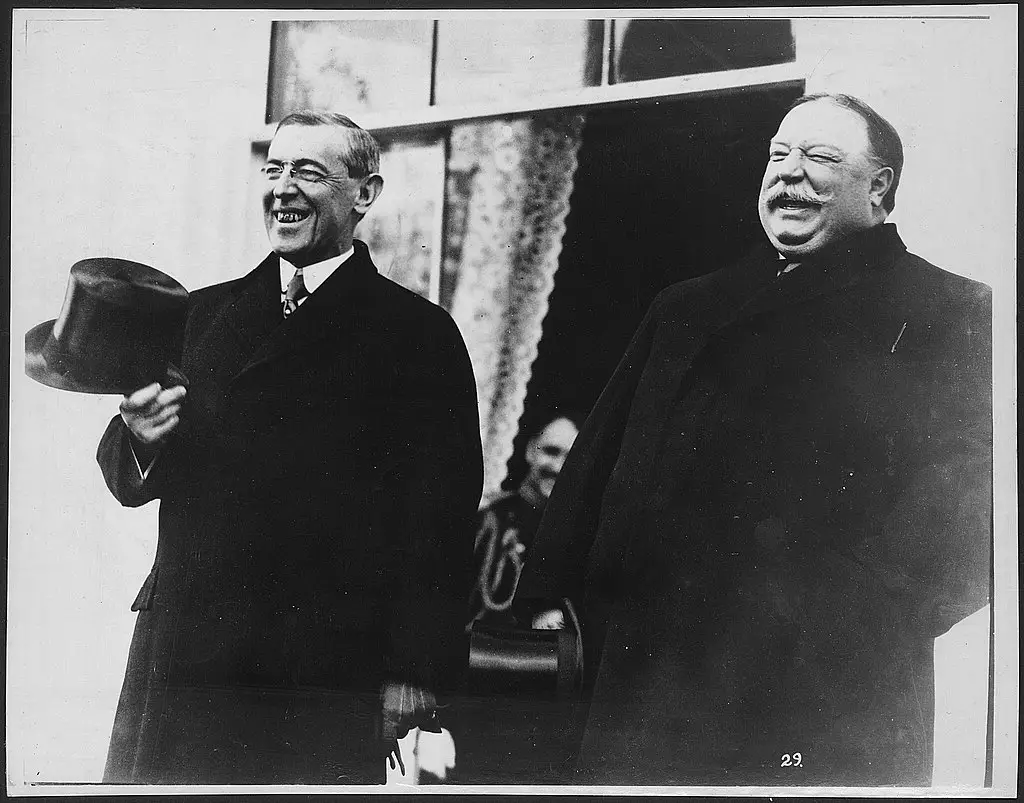

This status quo was challenged in 1909 when President Taft took office. As government growth outpaced available land in D.C., a campaign arose calling for undoing the decades-old retrocession and restoring Alexandria and its valuable land to the District of Columbia. Throughout Taft’s and later Woodrow Wilson’s presidencies, powerful political momentum existed behind reversing this critical piece of Washington D.C.’s history.

Supporters of Retrocession

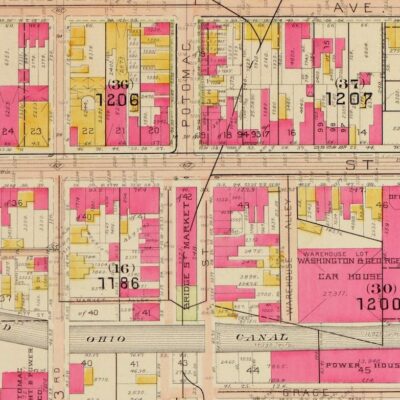

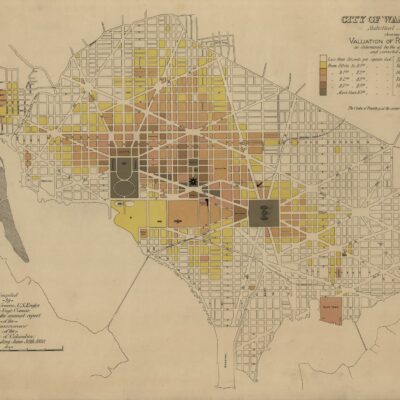

In 1909, the Washington D.C. Chamber of Commerce produced a map proposing the annexation of parts of Fairfax and Loudoun Counties in Virginia, urging President Taft and Congress to act quickly to address overcrowding concerns in the capital. As reported by The Washington Post in 1910, the Chamber argued retrocession was “necessary, not only for the proper growth of the seat of the National Government, but for the health, safety and morals of the community.” The Chamber’s proposal specifically identified lands they wished to reclaim, showing just how precisely they had planned this potential retrocession.

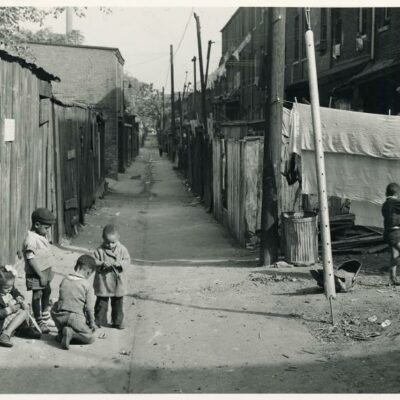

That same year, Alexandria residents were persuaded of the benefits of rejoining the District after a large factory fire proved the city’s fire department was inadequate compared to D.C.’s. The Washington Post reported in 1909 that the blaze “forcibly presented” the “advantages of the District form of government” regarding fire protection, leading many to believe retrocession would promote “progression and safety.” The Post noted that Alexandria’s mayor had to call on D.C. for backup during the fire, demonstrating the city’s need for the District’s more robust emergency services.

In December 1910, Alexandria citizens were pleased when Taft endorsed retrocession in his message to Congress, hoping to gain D.C.’s improved utilities and services, according to The Washington Post. Prominent local businesses and organizations clearly eyed the potential gains for Alexandria in becoming part of D.C. once again.

Taft and Congress Push for Retrocession

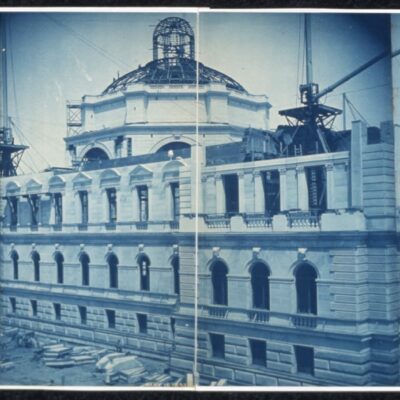

In early 1910, D.C. Commissioner John M. Casselman presented Congress with a retrocession proposal to rectify the “mistake” made in 1846, arguing the capital needed to expand and regain its original territory. As The Washington Post reported, Casselman laid out a detailed plan for undoing retrocession, noting precedents from other cities like Philadelphia and Baltimore that had successfully reclaimed lands.

Friends of retrocession believed the movement gained momentum when President Taft and members of Congress supported undoing the decades-old retrocession. The Washington Post reported in 1910 that their rationale was “the need for the District to expand to accommodate the growing government.” Powerful political figures argued retrocession was necessary for the capital’s growth and also as a matter of principle to restore its original borders.

In his 1912 State of the Union address, Taft asked Congress to “restore to the District of Columbia the portion of its territory taken away by the retrocession,” citing security concerns for the defense of the capital. Taft urged Congress to act, framing retrocession as critical to protecting Washington D.C. and asserting its status as the nation’s capital.

With Taft as a vocal advocate, the push for retrocession gained steam and appeared to have a real chance of succeeding after 60 years of the status quo. Powerful leaders in D.C. and Virginia lined up behind the campaign to dramatically reshape the capital’s geography.

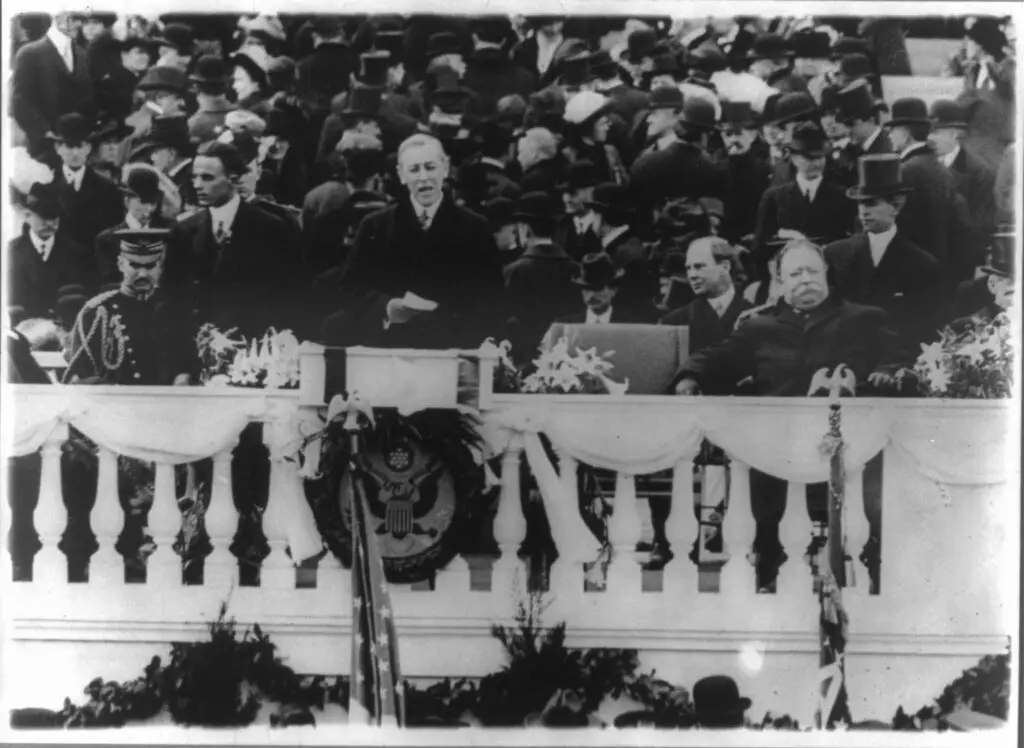

Shift in Support to Wilson Presidency

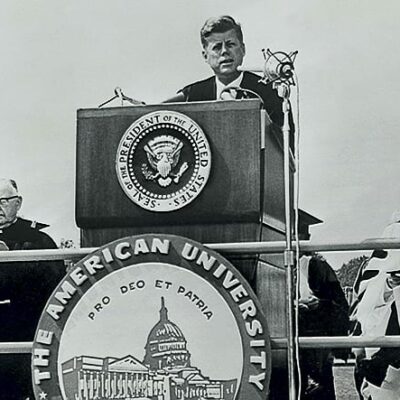

When Woodrow Wilson assumed the presidency in 1913, he also indicated support for retrocession of Alexandria County, believing it would benefit residents and provide more territory for the capital. As reported by The Washington Post, Wilson saw retrocession as mutually beneficial and stated he saw no constitutional barriers to the plan.

However, the transition of power from Taft to Wilson proved a major roadblock. Taft and Attorney General Wickersham considered suing Virginia over retrocession in Taft’s final days in office, but were unable to act before Wilson took over, The Post reported. Despite Wickersham’s belief in a strong legal case, the narrow window for action closed with the change in administrations.

Ultimately, the attempts to undo retrocession failed during this period, despite support from Taft, members of Congress, and some Virginia citizens. As The Post concluded, Virginia representatives resisted strongly, not wanting to lose valuable land and tax revenue. While momentum gathered in 1909-1913, the political will was insufficient to actually reverse the 70-year status quo.

Powerful figures like Taft and Wilson expressed support, and Alexandria residents were persuaded of the benefits. But Virginian politicians refused to surrender land, dooming the retrocession campaign. The capital would remain confined to its smaller borders set in 1846.