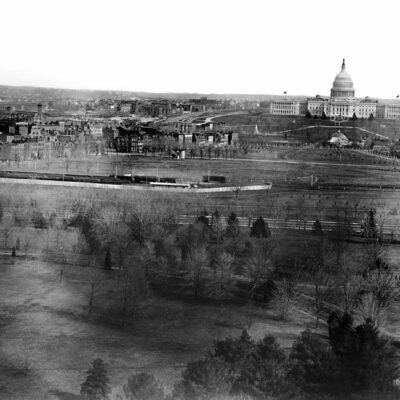

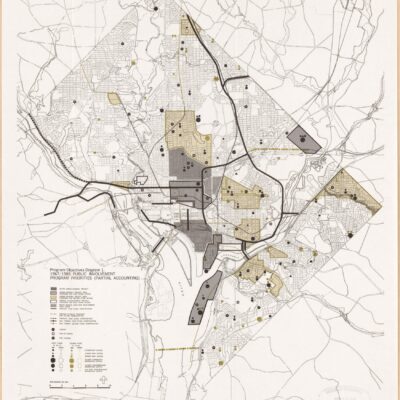

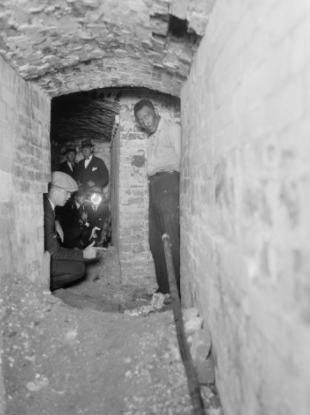

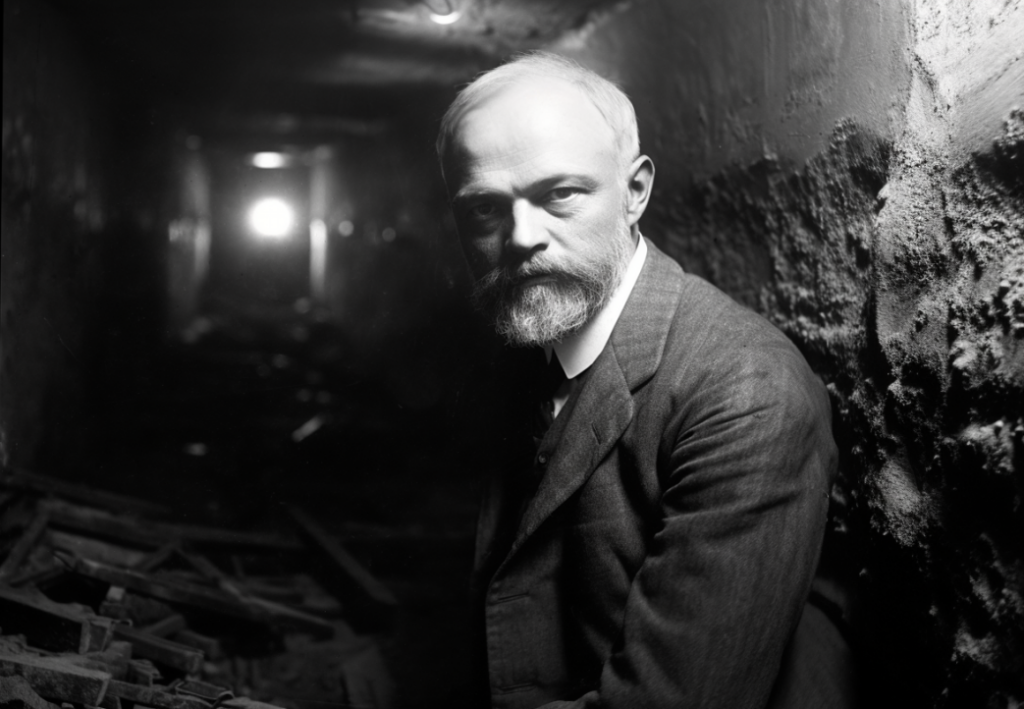

In September 1924, Washington D.C. was abuzz with a bizarre mystery. Construction workers demolishing homes near Dupont Circle stumbled upon something shocking lurking below the neighborhood: an intricate network of concrete tunnels stretching for hundreds of feet. As officials inspected the underground passageways illuminated by electric lights, they uncovered a secret world right under the capital’s streets.

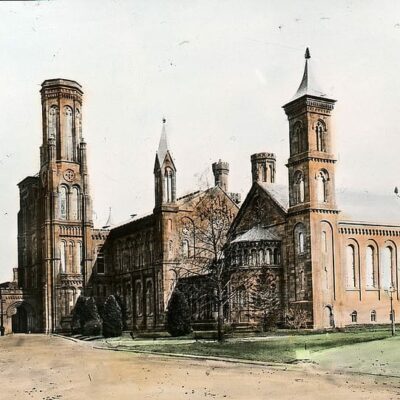

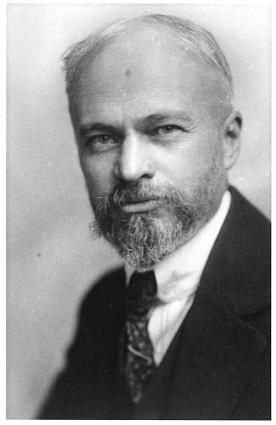

Who was responsible for this elaborate subterranean labyrinth? The tunnels were traced back to nearby properties owned by entomologist Harrison G. Dyar, who was affiliated with the Smithsonian. When questioned, he admitted to covertly digging the tunnels by hand over the past 6 years as a hobby, calling it “merely a pastime.”

Dyar claimed the tunnels allowed him exercise and privacy to conduct research in solitude. But this unbelievable explanation only deepened the mystery, sparking whispers of bootlegging, occult rituals, or something even more sinister. The exposure of what The Washington Post called Dyar’s “mystery tunnel diggings” damaged the scientist’s career and became a decades-long source of intrigue.

This fascinating saga reveals the eccentric side of a man who left his strange mark beneath Washington D.C.

Who Was Harrison Dyar?

Before the tunnels, Harrison was a prominent scientist working in Washington D.C. in the early 20th century. He served as an entomologist studying mosquitos and ways to control the spread of diseases like malaria. The New York Times described him as “recognized as the foremost authority in the United States on mosquitos and their relation to the transmission of disease” upon his death in 1929. Dyar made major advancements exploring the anatomy and life cycles of the pests. His dedication to the field earned him recognition and leadership roles in top scientific societies.

Outside of his esteemed career though, Dyar was known to exhibit eccentric behaviors. The Washington Post coverage portrayed him as an “oddball” based on some of his unusual hobbies and proclivities. He was fascinated with collecting butterflies, moths, and snakes—amassing enormous personal collections. He also had a preoccupation with physical strength and fitness. This manifested in the form of compulsive digging and tunneling projects that he conducted in solitude. But in the early 1900s, few suspected he was burrowing elaborate tunnels right under the streets of Dupont Circle. For years this was his deeply guarded secret until the sensational tunnel discovery of 1924 exposed his hidden side.

The Sensational Discovery of Dyar’s Tunnels

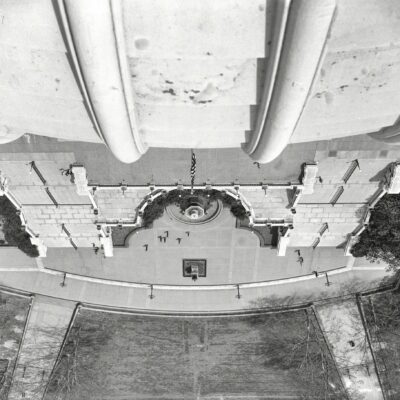

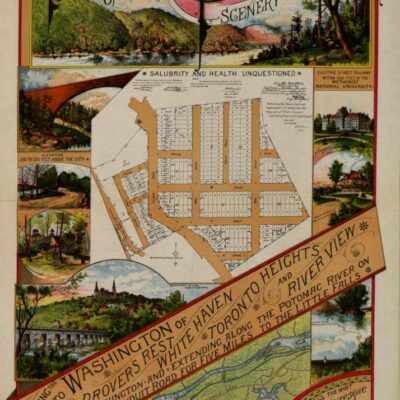

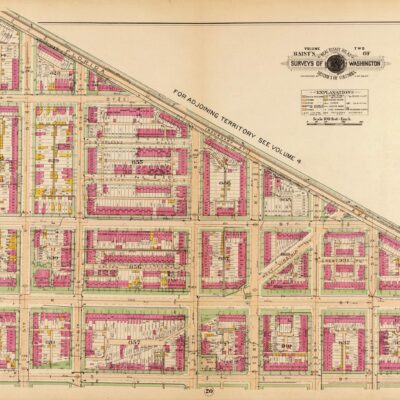

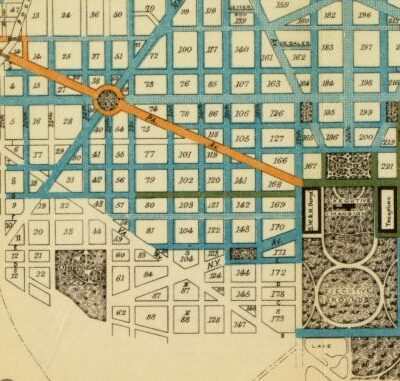

In September 1924, Dupont Circle was undergoing major redevelopment which led to the accidental unearthing of Dyar’s secret pastime. Construction workers demolished townhouses to clear space for new roads and stumbled upon a baffling find – “a maze of tunnels and underground rooms,” according to The Washington Post’s front page coverage on September 27, 1924. As officials investigated, they determined the tunnels stretched for hundreds of feet and connected to properties owned by Dyar.

When confronted, he confirmed he had single-handedly dug the tunnels over the years in his spare time, disposing of the dirt by dumping it in a gully using his wheelbarrow. “I did it for exercise,” Dyar told The Post, “Digging tunnels after work is my hobby. There’s nothing really mysterious about it.” He claimed the tunnel digging allowed him privacy, a distraction, and a physical activity he’d enjoyed since childhood.

His far-fetched explanations failed to satisfy investigators and the public. The elaborate underground lair engineered in secret raised alarm. A Post headline dubbed them “‘Mystery’ Tunnels” while another declared them “One of the Most Weird Structures Ever Built.” The exposure of Dyar’s obsessive hobby exposed him as quite an eccentric individual in the city.

Dyar’s Bizarre Explanations and Ongoing Tunnel Digging

His initial claims that the tunnels were just a casual hobby did not satisfy investigators. His far-fetched childhood tunnel digging stories only raised more questions. “I have been interested in tunnels and underground construction work since I was a boy. I constructed tunnels or caves whenever I could,” Dyar told The Washington Post on September 27, 1924. When confronted about the secrecy, he replied, “Had I told anybody, they would have thought I was crazy.” Even after the tunnels were publicly exposed in September 1924, Dyar audaciously continued expanding the subterranean network originating from his residence at 1512 21st Street NW.

Another article in The Washington Post gave new details on the tunnels, reporting that Dyar’s underground maze now consisted of “bewildering” passageways and rooms on multiple levels. The article stated he adamantly blamed random “vandals” for breaking into his tunnels and causing damage, though investigators remained skeptical of his claims. According to the Post’s firsthand account, the tunnel system had grown even more elaborate, with new stairways leading down to additional rooms, all meticulously engineered and electrically lit. However, his brazen decision to keep digging even after authorities had uncovered his secret pastime only heightened public suspicion and curiosity about the true purpose behind the hidden tunnels.

According to the Post, Dyar’s tunnels contained elaborately decorated rooms and empty alcohol bottles, suggesting the tunnels served as his private sanctuary. A November 22, 1906 Post article titled “Buys Strip To Aid Big Tunnel” revealed Dyar’s longtime tunnel digging, as he bought property next to his home to facilitate additional tunnel expansions.

The elaborate and unnecessary nature of the tunnels pointed to a disquieting psychological compulsion beyond mere hobby for Dyar. He clearly relished having a secret subterranean where he could disappear for hours on end without detection. But the sensational public exposure of what the Post called his “mystery tunnel diggings” ultimately collapsed Dyar’s eccentric second life.

Dyar’s Brief Ownership of the Chastleton

As an aside, it’s worth looking at his brief ownership of the luxurious Chastleton apartment building in Washington D.C. In February 1925, Dyar purchased the Beaux Arts style apartment complex located at 1701 Sixteenth Street NW for $2.3 million, then named the Sixteenth Street Mansions. The lavish building was one of the most upscale residential spaces in the city at the time.

However, Dyar sold the building just one month later in March 1925 – a significant loss on his very recent multi-million dollar investment – though the terms of the deal were not disclosed at the time. While Dyar’s motivations are unclear, his rapid purchase and sale of the elite Chastleton apartment complex provides yet another glimpse into the unusual eccentric lifestyle of the man who dug covert tunnels below Dupont Circle.

Dyar’s Reputation Takes a Hit

While quiet initially about his personal life, some revelations did emerge about Dyar after the tunnel exposure in September 1924. An earlier 1916 Washington Post article had made a brief reference to him divorcing his wife amid unspecified rumors about their relationship.

However, the revelation of his covert tunnel digging in 1924 brought intensified public scrutiny and damage to his reputation. The elaborate hidden tunnels and his far-fetched explanations created a media sensation in Washington D.C. The Washington Post published numerous front page articles exposing the “bizarre mystery” and “weird tunnels.” This frequent newspaper coverage of his odd hobby clearly took a further toll on Dyar’s already peculiar public image.

According to later accounts, the relentless public ridicule impacted his scientific career and standing in the city’s social circles. But he appeared undeterred, obstinately continuing to dig and expand the tunnels even after authorities uncovered his secret pastime. He offered no apologies or regrets over the tunnel obsession that consumed so much of his life. The motivations behind his eccentric tunneling fixation remain an enduring mystery decades later. While his legacy is marked by brilliance and eccentricity, the tunnel scandal cemented Dyar’s notoriety in his own time.

Segments of Dyar’s tunnels still exist below Washington D.C. and curiosity seekers occasionally open them for tours, attracting visitors. The saga still fascinates historians and locals, keeping his legacy alive. While an oddball character, he pioneered entomology and left his eccentric mark on the city in a subterranean style all his own.

Last Will and Testament

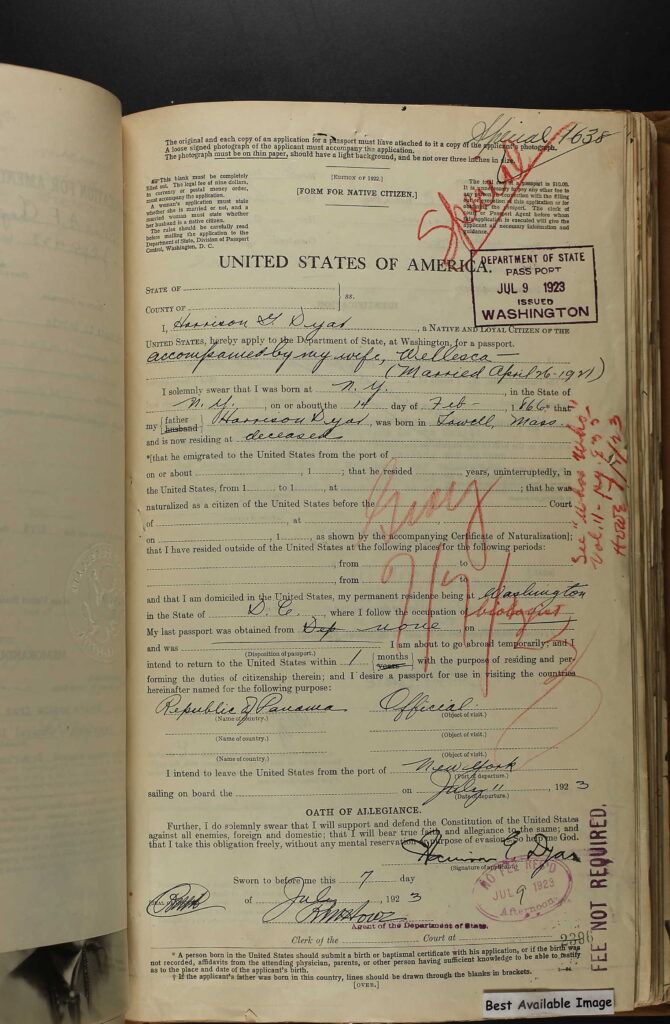

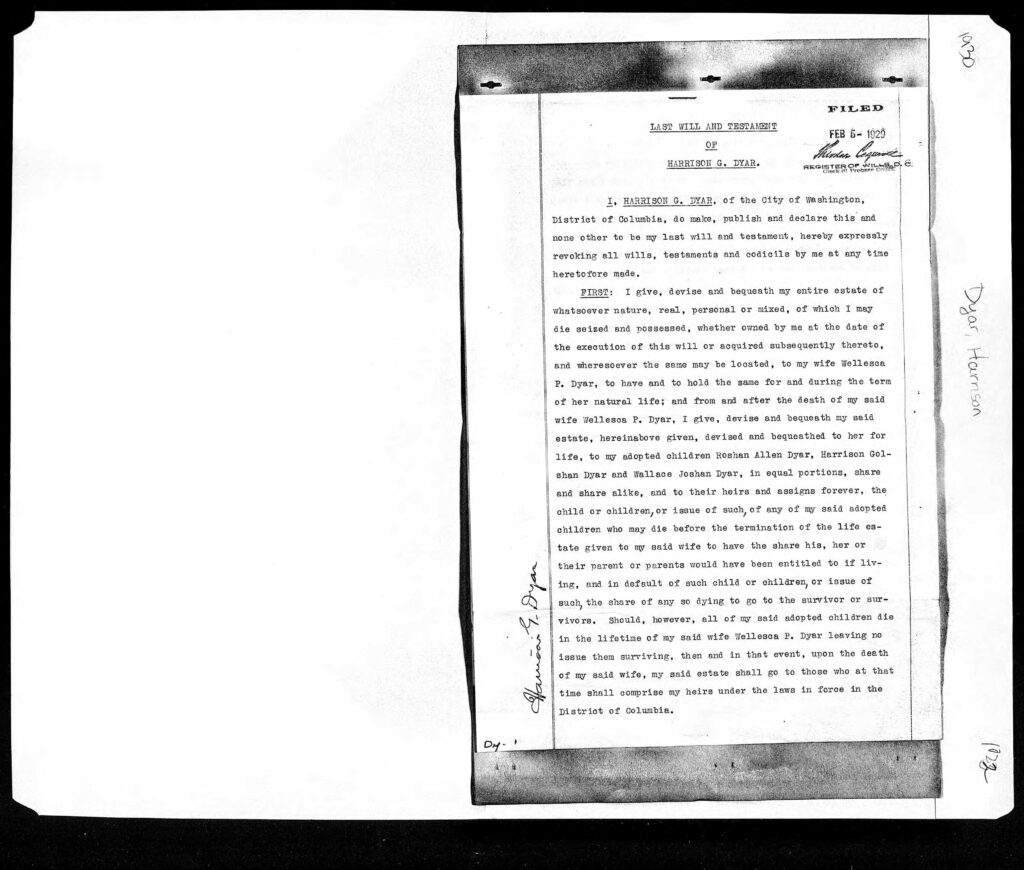

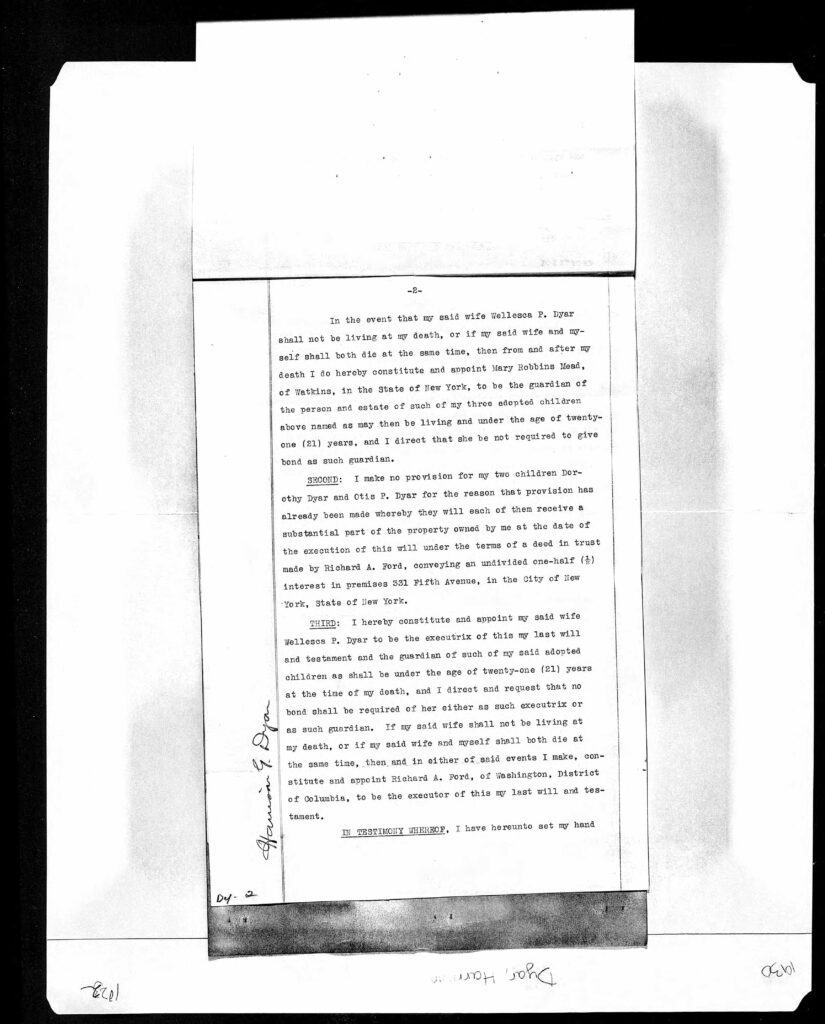

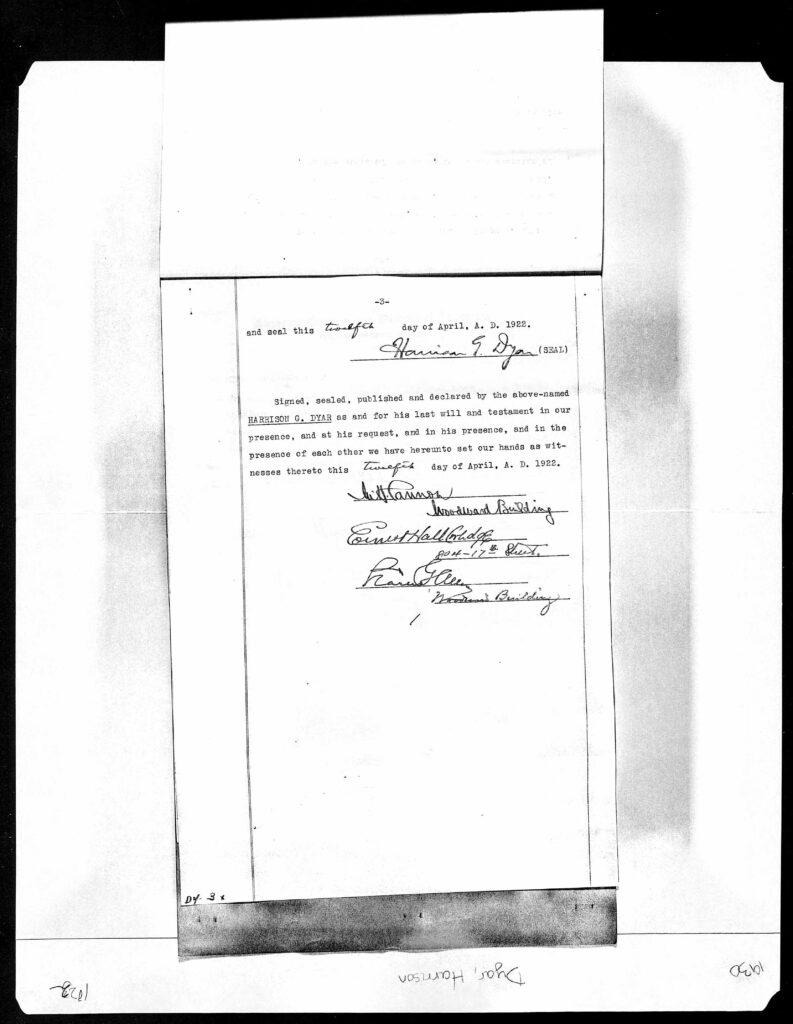

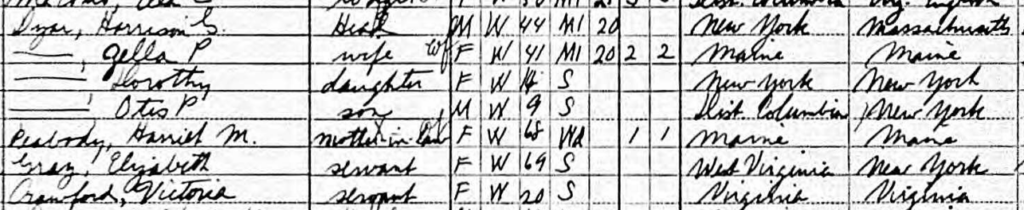

As an addendum to this story, I’m adding a passport application he made in 1923 for a trip to Panama as well as his last will and testament, dated April 12, 1922. We uncovered these in our research on Ancestry.com.