This is a guest post by Angela Harrison Eng.

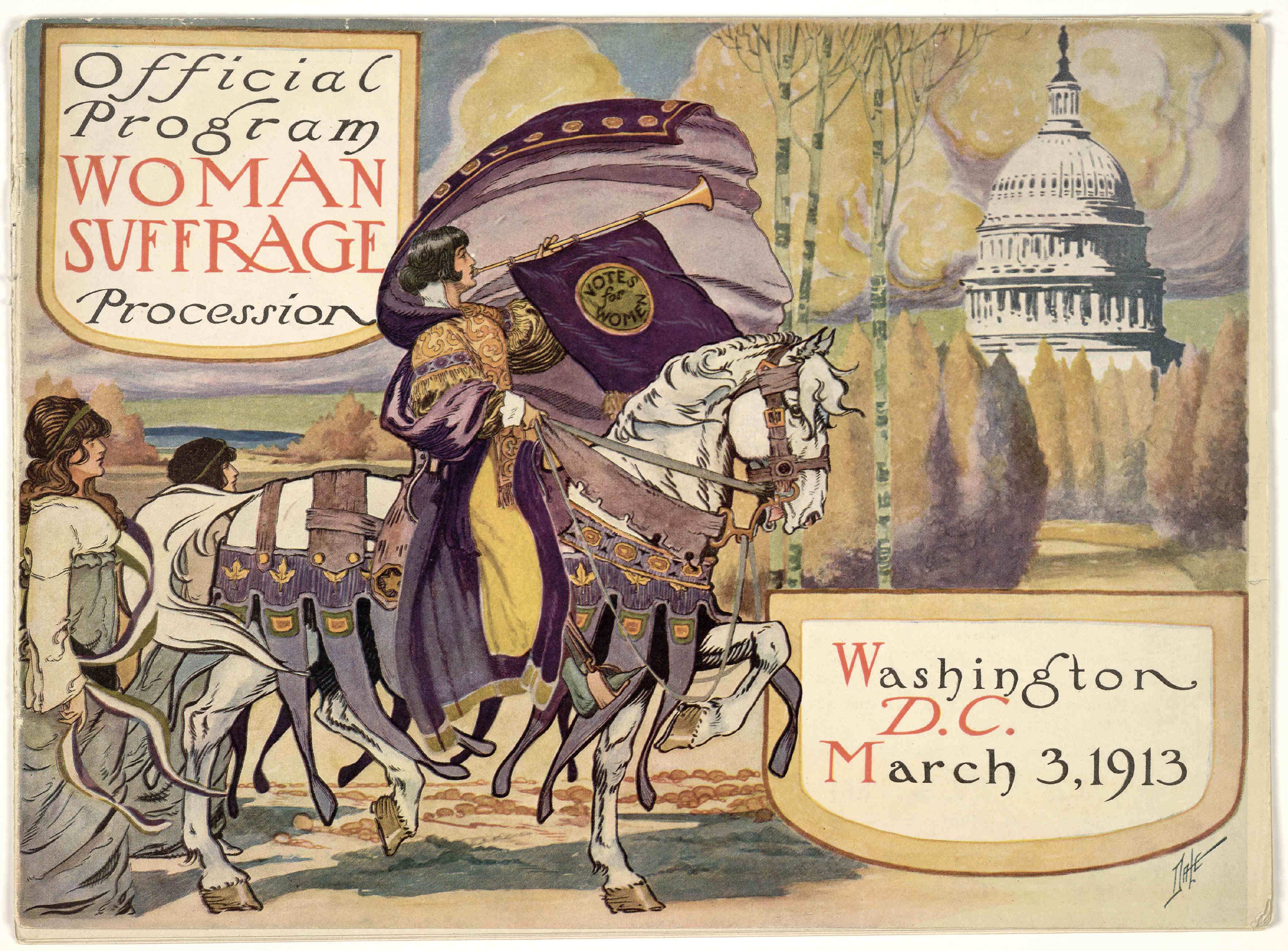

March 3, 2013, was an important day in women’s history, yet it went virtually unnoticed in the public eye. Before women gained the right to vote nationwide in 1920, the efforts of suffragettes in the United States were brazen, courageous moves that were designed to gain the attention of the public—and the president of the United States. One of these bold moves was the Women’s Suffrage March, which took place on March 3, 1913.

According to an article in Smithsonian Magazine, a smattering of states had given women the right to vote by spring of 1913. However, the women’s suffrage movement was stalled. A woman named Alice Paul, a member of the National Women’s Suffrage Association, would change that. She organized a spectacular parade that would “make Washington take notice.” The date chosen for the event was March 3, 1913.

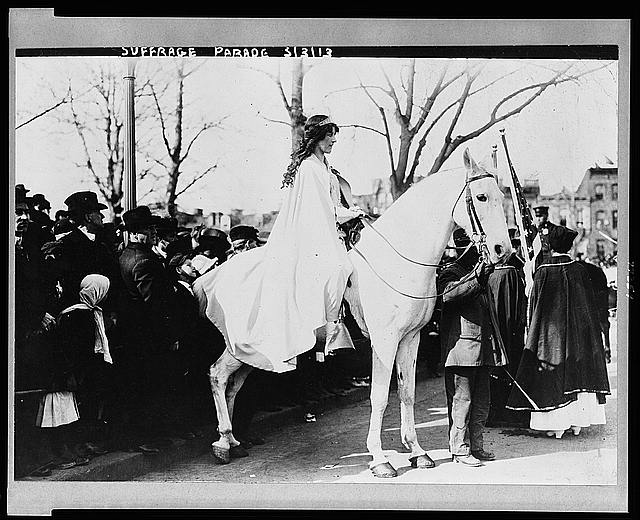

The New York Times noted it was to be a grand affair, with over 20 floats, a number of bands, cavalry squads, and chariots. Inez Milholland, a lawyer and prominent suffragist, was to be the herald of the parade and lead on horseback.

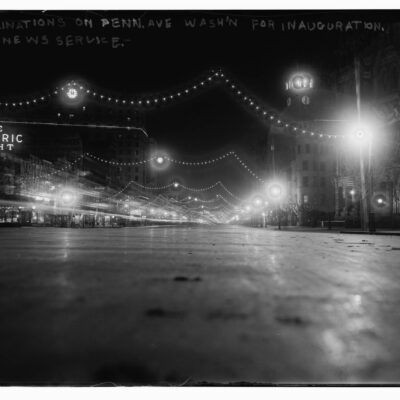

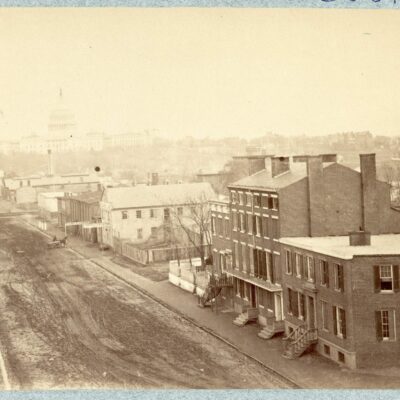

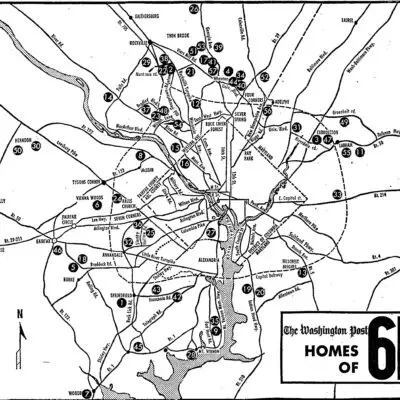

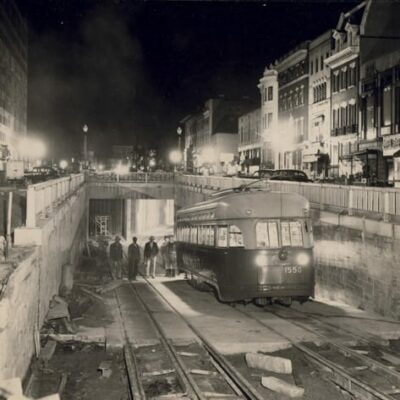

The Washington Post outlined the parade procession, noting “the route will be along Pennsylvania Avenue to 15th Street, the south of the Treasury steps to the White House ellipse and directly across the ellipse to Memorial Continental Hall.” On the Treasury steps was to be a tableau featuring German actress Hedwig Reicher as Columbia. The final rally was to take place at the Continental Hall, with Helen Keller as the principal speaker.

Paul deliberately chose the date of March 3rd because the next day was Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. The goal, as stated in a January 1913 edition of The Atlanta Constitution, was to ensure “no man would be safe from suffragettes” and that “not a single man who attends the inauguration will be allowed to depart without having heard at least one suffrage argument.”

Interesting sidenote: A Washington Post article from late February noted some rumors, among them that “Pretty girls are being offered $3 to march in the suffrage procession March 3.” The reason was because “suffragists want to give the impression that many pretty girls are in favor of suffrage.” The article went on to say antisuffragists were offering girls $3 to not march in the parade. Both suffragists and antisuffragists, however, called these rumors unfounded and total hearsay.

This article is not the first instance in which women’s looks were mentioned. One article from the Post refers to Inez Milholland as “the beautiful society girl of New York,” who “gave complete support to the claim of suffragists that some of the most beautiful women in the country are active in the equal rights cause.”

The day of the parade showed many women, pretty or not, believed in the cause. Most sources put the total of marchers around 5,000. However, the procession was fraught with troubles from the start. Many protesters showed up and attempted to disrupt the parade. The result, according to the Atlanta Constitution, was that these 5,000 or more women “practically fought their way foot by foot up Pennsylvania Avenue, through a surging mob that completely defied the Washington police, swamped the marchers, and broke their procession into little companies” and “they could only finish when Calvary troops from Ft. Meyer were called in to control the crowds.”

Apparently, it took an hour to move 10 blocks, and the marchers had to endure a number of insults from the crowds along the way. Inez Milholland was reported to have ridden down a mob blocking the parade route on her horse, demanding the marchers be allowed to continue.

The tableau went on as planned, and the rally at the end of the day ended up more of a complaint session than a rally. Helen Keller was said to be “so exhausted and unnerved by the experience that she did not speak as planned.” Nevertheless, Alice Paul still considered the march a success.

An inquiry was launched and congressional hearings were held over the treatment of the women in the parade, which resulted in the firing of the D.C. police superintendent. The hearings thrust women’s suffrage into the national spotlight, but it would take another 7 years and many more protests before women’s right to vote became the law of the land.

![Capital Transit demonstration run of a Twin Coach articulated bus (a model they did not end up using), April 3, 1948. This turnaround is still used by buses today [photo by Robert S. Crockett].](https://ghostsofdc.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2015/12/10896004463_3f7d28bb16_o-400x400.jpg)