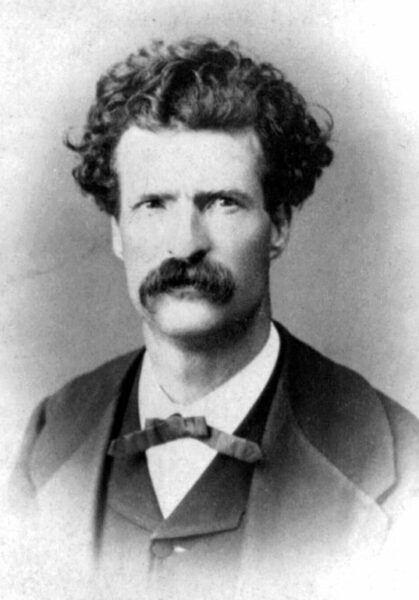

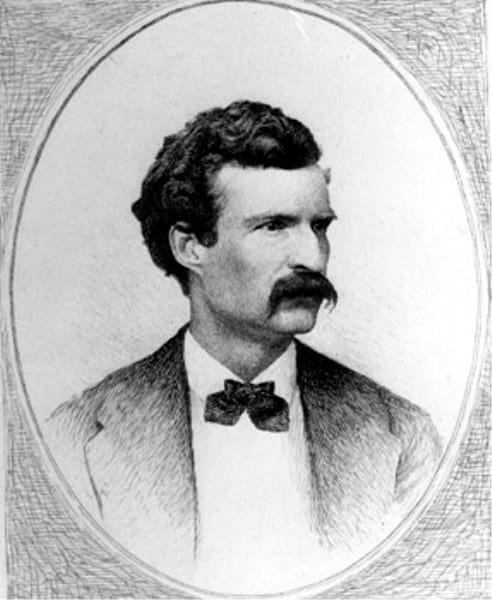

First appearing in Mark Twain’s Washington letter to the Territorial Enterprise on March 1, 1868, the story of “The Man Who Stopped at Gadsby’s” was a tale that stuck in Twain’s psyche, and he repeated it in full in his 1880 book A Tramp Abroad. Twain initially relates the story in his dispatch to the Enterprise in relation to a recently arrived office seeker in Washington pursuing appointment as the postmaster of San Francisco.

He was the thirty-seventh person known to be chasing the position. “He is a good enough man and may get the place, but it will cost him more trouble and vexation than he is promising himself, no doubt,” Twain writes. With the Senate and President Johnson at odds, the man was in a precarious position. According to Twain, “He says he can’t see that there is anything to be done but get the President to appoint and the Senate to ratify. Certainly that is all, truly enough. It was all that was to be accomplished by the thirty-six. He says he means to show the President what the Pacific coast papers say about him, and he means also to tell him all about how the Post Office has heretofore been managed and how he would improve that management the moment he got into office.” However, the man was unlikely to secure the position, Twain estimated, because “he don’t say he would swear by Andrew Johnson and labor for his behest alone—which is much more important. And he don’t take into consideration that the moment he gets the President in his favor, the Senate will be down on him for it, and that if he gains the Senate’s affections first, the President will be down on him.”

Even after hearing the tale of the man who stayed at Gadsby’s from Twain’s friend Riley, the San Franciscan’s naïveté held firm when he said he planned to stay in Washington but a week. “He says he don’t care anything about making an extended stay in Washington—he only wants to get the appointment and look around the great public buildings a little, and then he is off,” Twain wrote. The man had been warned, although Twain didn’t think “he saw the point of it or not. It was a little story that has been related with great spirit many thousands of times to office seekers and claim-hunters who were only going to tarry a few days in Washington.”

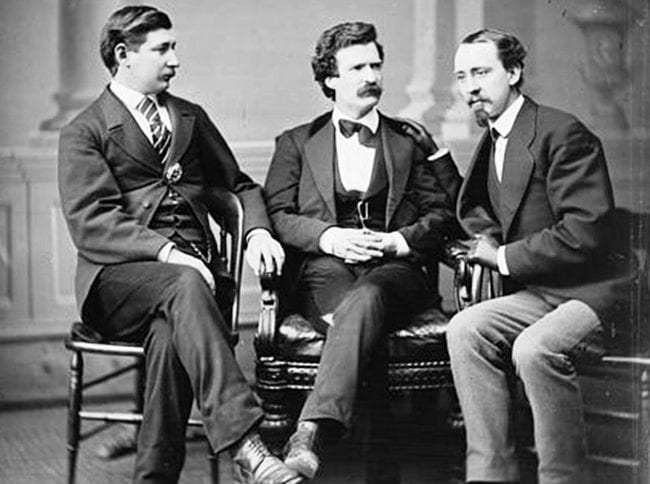

Twain wrote years later that he and his friend John Henry Riley had allegedly met the innocent office seeker and relayed the cautionary Gadsby’s Hotel tale to him personally. One night, near midnight, Twain and Riley were coming down Pennsylvania Avenue “in a driving storm of snow when the flash of a street lamp fell upon a man who was eagerly tearing along in the opposite direction.” On noticing Riley, the man stopped dead in his tracks. “My name is Lykins,” the man said. “I’m one of the teachers of the high school—San Francisco. As soon as I heard the San Francisco postmastership was vacant, I made up my mind to get it—and here I am.” Riley asked if the man had secured the position. “Well, not exactly got it, but the next thing to it,” the man said. “I’ve brought a petition, signed by the Superintendent of Public Instruction, and all the teachers, and by more than two hundred other people. Now I want you, if you’ll be so good, to go around with me to the Pacific delegation, for I want to rush this thing through and get along home.” Riley, whom Twain admired as “the most self-possessed and solemnly deliberate person in the republic,” responded to the man “in a voice which had nothing mocking in it—to an unaccustomed ear” by saying: “If the matter is pressing, you will prefer that we visit the delegation to-night.”

The man answered with enthusiasm. “Oh, to-night, by all means! I haven’t got any time to fool around. I want their promise before I go to bed—I ain’t the talking kind, I’m the doing kind!” Riley cajoled Lykins, telling him, “[Y]ou’ve come to the right place for that.” After considering the particulars of how Lykins and Riley could rapidly ensure the appointment would go through the next day before Lykins had to return to San Francisco, Riley asked, “You couldn’t stay a day…well, say two days longer?”

Lykins responded emphatically, “Bless your soul, no! It’s not my style. I ain’t a man to go fooling around—I’m a man that does things, I tell you.” The storm had picked up, “the thick snow blowing in gusts.” Poised, Riley looked at Lykins and asked, “Have you ever heard about that man who put at Gadsby’s once? But I see you haven’t.” Riley “backed Mr. Lykins against an iron fence, buttonholed him, fastened him, with his eye, like the Ancient Mariner, and proceeded to unfold his narrative as placidly and peacefully as if we were all stretched comfortably in a blossomy summer meadow instead of being persecuted by a wintry midnight tempest.” Riley began to tell the tale: “It was in Jackson’s time. Gadsby’s was the principal hotel then.”

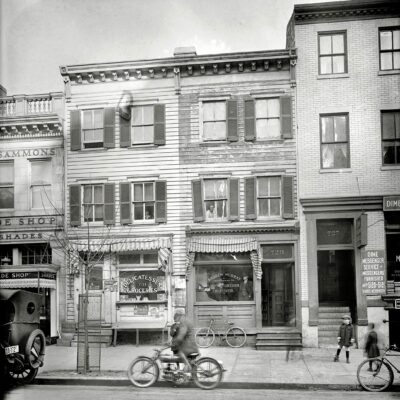

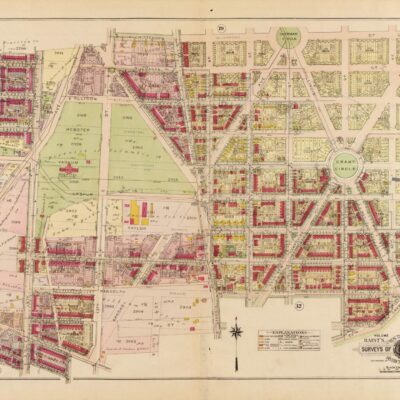

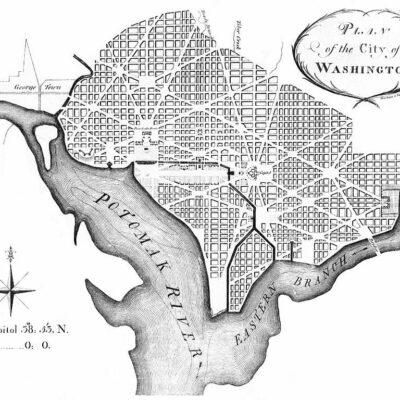

According to local historian John DeFerrari, “Originally founded in 1827 by John Gadsby, the National Hotel was located on Pennsylvania Avenue at 6th Street, NW. Gadsby, who had run Gadsby’s Tavern in Alexandria in the 1790s, came to Washington in the early 1820s, taking over a tavern and hotel at 19th and I Streets, NW. That place was too small and out of the way, however, so in 1827, he purchased the row of federal townhouses on the northeast corner of Pennsylvania Avenue at 6th Street, NW, and combined them to form the hotel he called the National but which was more frequently known as Gadsby’s Hotel in its early days.”

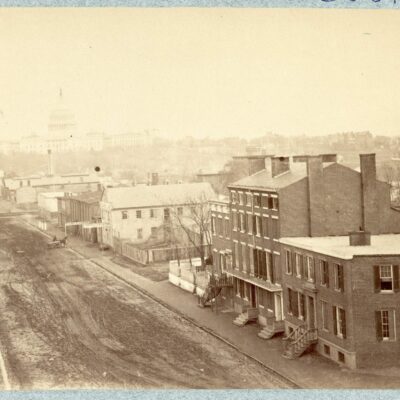

By the time Riley relayed the tale Gadsby’s Hotel was only used in conversation by old Washingtonians. The National Hotel was its current name and known all around town for its telegraph office, right down the street from the Capitol. The story Riley spun was a cautionary tales from the early days of Washington City.

“Well, this man arrived from Tennessee about nine o’clock one morning, with a black coachmen and a splendid four-house carriage and an elegant dog, which he was evidently found and proud of,” Riley said. The man then “drove up before Gadsby’s, and the clerk and the landlord and everybody rushed out to take charge of him; but he said ‘Never mind,’ and jumped out and told the coachman to wait.” The man was in a rush and didn’t have time for a meal. He had “only a little claim against the Government to collect, would run across the way to the Treasury and fetch the money, and then get right along back to Tennessee, for he was in a considerable hurry.” Around eleven o’clock that night, the man returned to Gadsby’s Hotel and took a bed and put his horses up, vowing to collect on his claim the next morning. According to Riley, this was January 3, 1834.

“Well, on the 5th of February, he sold the fine carriage and bought a cheap second-hand one—said it would answer just as well to take the money home in, and he didn’t care for style,” Riley continued. By August 11, the man from Tennessee sold a pair of his fine horses, leaving him two of the four he came to Washington with. He reasoned “there wasn’t so much of his claim but he could lug the money home with a pair easy enough.” On December 13, he sold another horse, and on February 17, 1835, “he sold the old carriage and bought a cheap second-hand buggy.” On August 1, he sold the buggy, and on August 29 “he sold his coloured coachman.” Eighteen months later, on February 15, 1837, he downgraded from his sulky to a saddle by reasoning that “horseback riding was what the doctor has always recommended.” On April 9, 1837, he sold the saddle and alleged he could now ride back to Tennessee bareback.

Riley pressed on with his story: “On the 24th of April he sold his horse—said, ‘I’m just 57 to-day, hale and hearty—it would be a pretty howdy-do for me to be wasting such a trip as that and such weather as this on a horse when there ain’t anything in the world so splendid as a tramp on foot through the fresh spring woods.” The man would “make my dog carry my claim in a little bundle anyway, when it’s collected. So to-morrow I’ll be up bright and early, make my little old collection, and mosey off to Tennessee, on my own hind legs, with a rousing good-bye to Gadsby’s.” If only the man was so fortunate. On June 22, he sold his dog: “I’d a blamed sight rather carry the claim myself, it’s a mighty sight safer; a dog’s mighty uncertain in a financial way—always noticed it—well good-bye, boys—last call—I’m off for Tennessee with a good leg and a gay heart, early in the morning!”

The noise of the wind and the pelting of the snow filled the silence as Riley finished his story. An impatient Lykins asked, “Well?” Riley, according to Twain, said, “Well, that was thirty years ago.” Riley was friendly with the “old patriarch. He comes every morning to tell me good-bye. I saw him an hour ago—he’s off for Tennessee early to-morrow morning—as usual; said he calculated to get his claim through and be off before night-owls like me have turned out to bed. The tears were in his eyes, he was so glad he was going to see his old Tennessee and his friends once more.” Again there was a silent pause. “That is all,” Riley, said. “Well, for the time of night and the kind of night, it seems to me the story was full long enough. But what’s it all for?” asked Lykins.

“Oh, there isn’t any particular point to it,” Riley admitted. “Only, if you are not in too much of a hurry to rush off to San Francisco with that post-office appointment, Mr. Lykins, I’d advise you to ‘put up at Gadsby’s’ for a spell and take it easy. Good-bye. God bless you!” With that, “Riley blandly turned on his heel and left the astonished school-teacher standing there, a musing and motionless snow image shining in the broad glow of the street-lamp.”

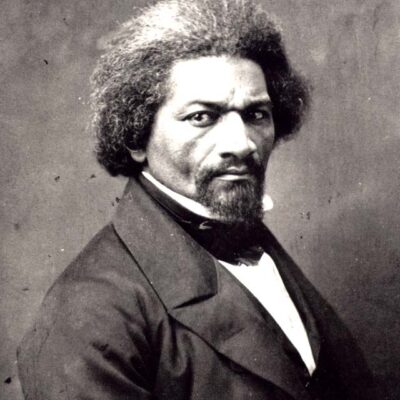

Also, I will be giving talks on Mark Twain in Washington, D.C. in the coming months. Before the talk at Politics & Prose on Saturday, January 4th, 2014 at 1pm, John will be spending the upcoming weeks celebrating Frederick Douglass as part of the DC Public Library’s DC Reads programming.