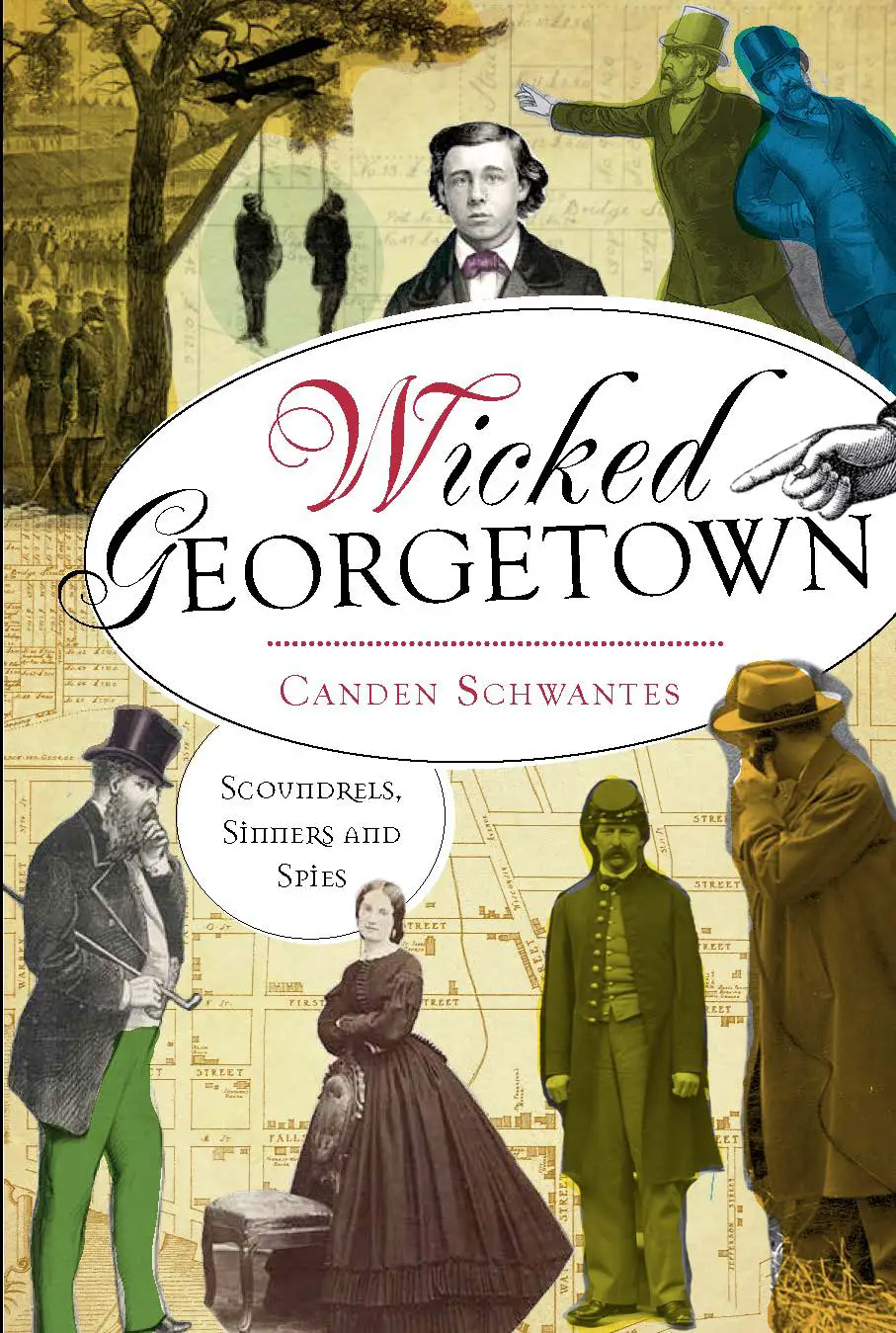

This guest post was written by Canden Schwantes and is an excerpt from her book Wicked Georgetown: Scoundrels, Sinners and Spies.

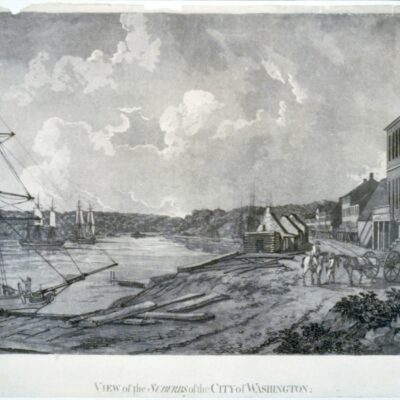

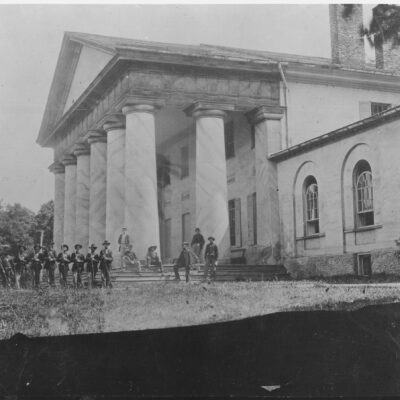

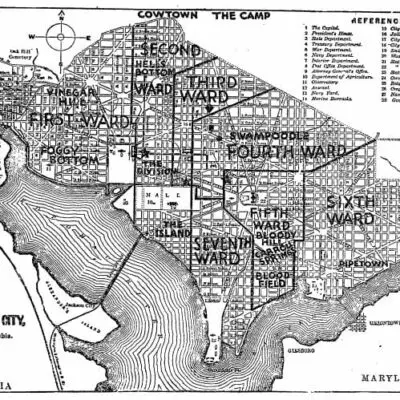

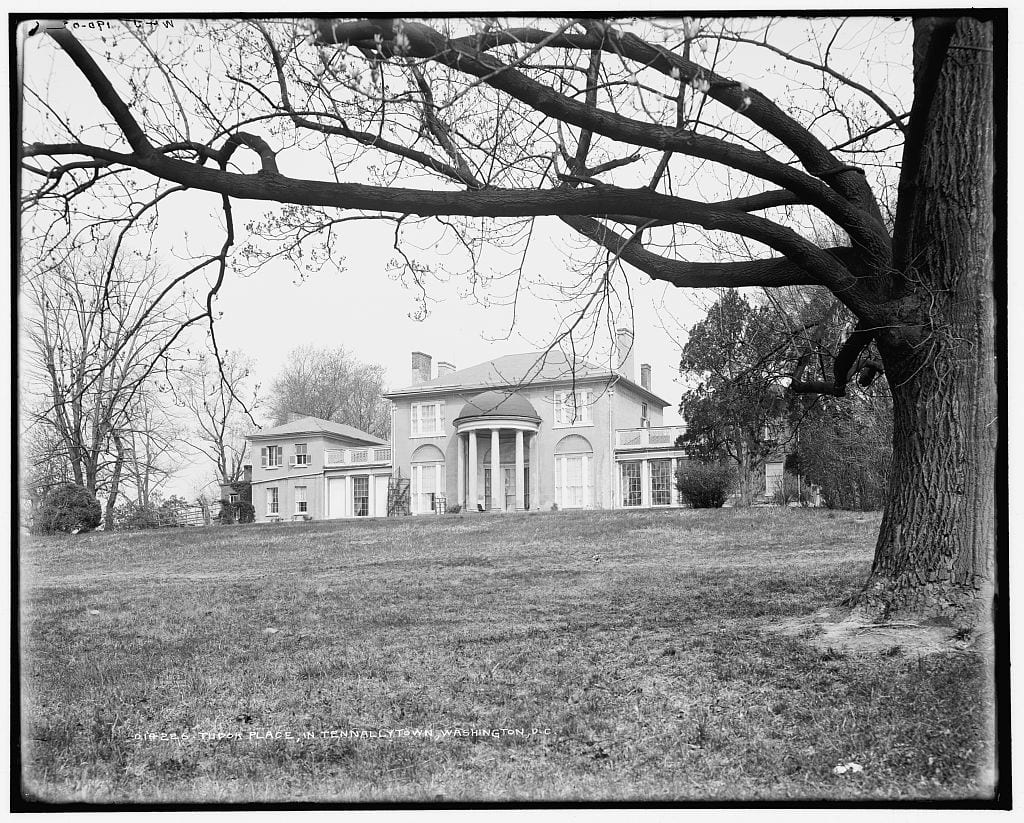

William Orton Williams and Walter Gibson “Gip” Peter were cousins and as part of the Peter family were descendents of George Washington’s step-granddaughter. They both grew up at Tudor Place in Georgetown, home of the Peter family from its completion in 1816 to the death of the last owner in 1983. William’s mother, America Peter, was one of the three sisters born in Tudor Place to a seemingly patriotic family. The sisters were named America, Columbia and Britannia. But the patriotism to the United States as a whole did not extend past the naming of children. As many of the families in Georgetown, the Peters had Southern sympathies. Their relatives, the Lee family of Virginia, only encouraged this support.

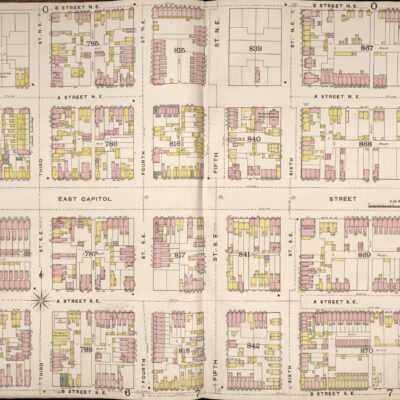

Williams was only a young boy when both his parents passed away. Afterward, he moved to live with relatives at Arlington House (what is now Arlington National Cemetery) and Tudor Place. The owner of Arlington House was George Washington Parke Custis, Robert E. Lee’s father-in-law. In one of many acts of nepotism in the military at the time, Lee petitioned to have Williams commissioned in the United States Army. As a second lieutenant in Lee’s Second Calvary, Williams was assigned as General Winfield Scott’s personal secretary.

In 1861, as the Southern states started to secede, so too did Robert E. Lee and William Orton Williams. But General Scott did not accept the resignation of his personal secretary immediately. With fear that he might have some knowledge that could benefit the Confederate army, Williams was imprisoned for several weeks.

Williams did not have the greatest reputation. He was seen as an arrogant man. After all, he had acquired his position due to family connections and not because of any education or skill on his part. He was also known for killing a soldier who refused his orders. But despite his inability to get along with his fellow soldiers, he did well in the Confederacy. An official name change to Lawrence Orton Williams and a transfer provided him with a fresh start, as did the arrival of his cousin Gip, who had been a scout in Virginia but put in for a transfer at Williams’s request. Colonel Williams, now in command of the Second Brigade of Major General Martin’s cavalry, had his cousin at his side and fortune on his side.

Around this same time, Union officers Colonel Lawrence W. Auton and Major George Dunlop were given orders to inspect the Union outposts in the Cumberland and Ohio areas. While traveling along the road with their orderly and possessions, they came across some enemy soldiers. Running for their lives and without a thought of what might be lost in the scuffle other than their heads, Auton and Dunlop escaped at the cost of losing their belongings.

When the soldiers arrived at Fort Granger, they used signed orders from General William Rosecrans and the War Department to gain an audience with Colonel Baird. There was some suspicion due to their civilian overcoats and outdated headwear, but Baird could find little reason to doubt their story and readily assisted where he could. Auton had requested passes that would allow them to continue on to Nashville as soon as possible, as well as a $100 loan to assist in the journey. The other officers at the fort put little faith in the visitors’ story, but Baird did not accept their concerns. Many refused to contribute to the loan, and in the end, Baird only had $50 to offer. As the evening waned, Auton and Dunlop said their thanks and goodbyes and rode off on their way to Nashville. At least this was the assumption of Colonel Baird. After they left, Baird realized that he had never seen them inspect the outpost at all. If that was their only reason for being in the area, why had they not taken a look around the fortifications? Later reports from other men at the post state that they did indeed perform a detailed and thorough walkthrough.

Baird, previously an attorney, had been in the military for less than year. With little formal military training, his actions were not always supported by his men. Though Baird believed the inspectors, few others did. When lifelong soldier Colonel Louis Watkins arrived shortly afterward, Baird related the evening’s happenings to seek out his opinion. Watkins thought it best to gain more information and rode out to find the two men. We have no way of knowing how Watkins coerced Auton and Dunlop to return to the fort. The two inspectors were not returned by force, and it is likely that they had been asked to collect some dispatches to bring with them on their way to Nashville.

Upon returning to the fort, it was not dispatches they found but an armed guard. The inspectors persisted with their story but could not offer proof. The proof would be found through communication with Rosecrans to verify the identity of the men and their orders. Fog prevented the signal stations as an option, and the telegram sent to Murfreesboro was not deemed a priority. Fort Granger waited nearly three hours to receive a reply that there had been no such men to his knowledge.

But the questions of veracity could have been answered without the long-awaited telegram. The orders from Rosecrans, signed by James A. Garfield, wrongly identified Garfield’s position as assistant adjutant rather than chief of staff. The orders from the War Department were penned on regular stationary with no official letterhead. While Baird had noticed the oddities of their uniforms, he did not see that Auton wore the wrong shoulder boards for an officer staffed by the War Department. However, the orders did state that Auton was a cavalryman, and this could have explained Auton’s uniform. The two men arrived through enemy territory with no armed escort and still were able to escape. No—it was not likely they were who they said they were.

With further interrogation, the two men admitted the farce but denied being spies. Colonel Lawrence W. Auton was indeed a colonel in the Confederate army named Lawrence Orton Williams. Traveling with him was Lieutenant Walter Gibson Peter. But they were not on a mission to retrieve privileged information about the fort or its officers; they were acting on a bet made with fellow Confederate officers that they could eat with and borrow money from the fort’s commander.

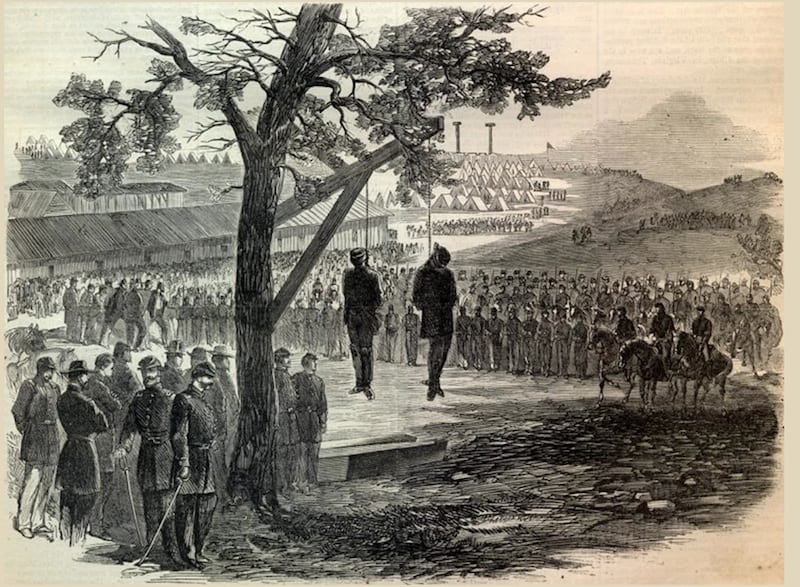

For a short time, they had won the bet. But in the end, it cost them their lives. With orders from above to call a drumhead court-martial tribunal, Baird was forced to do just that. During times of war, trials were more often than not just for show. There is no innocent until proven guilty, and a set punishment is determined by the crime, regardless of extenuating circumstances. It took less than one hour for the tribunal to declare the men guilty of spying. Watkins eventually recognized Williams. They had served together in the U.S. Army before the war. Watkins and Baird attempted to intervene on the spies’ behalf, but it was nearly 4:00 a.m, and Rosecrans and Garfield had gone to bed with direct orders not to be disturbed.

Williams and Peter handled their sentences with dignity and grace. In his statement during the trial, Williams admitted that he knew the consequences of being found guilty and was fully prepared to accept them. He did plea for the release of young Peter, but to no avail. They never admitted to being spies, only to a duplicitous manner of gaining entrance. Even in the letters they wrote to their loved ones at home, the two declared their innocence.

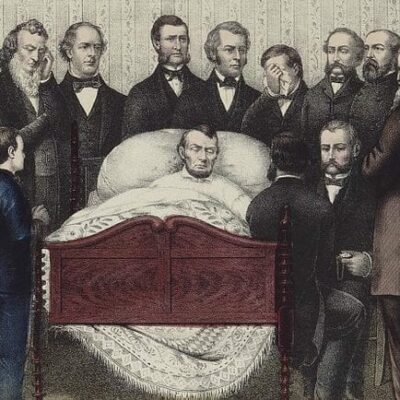

A final telegram was sent to Rosecrans. Baird made it known that these men were relatives of General Robert E. Lee and that Williams’s father had served with Rosecrans in the Mexican-American War. Three hours after the scheduled time of execution, there was still no reply.

As ordered, the men were hanged. It took them twenty minutes to die. Though all were agreed that it was right to hang men condemned as spies and that the two men had brought the actions unto themselves, it was a difficult event to participate in. Both Baird and Watkins refused to watch. All accounts report of the composure and bravery of Gip Peter and William O. Williams, whose lasts words were, “Let us die like men.”

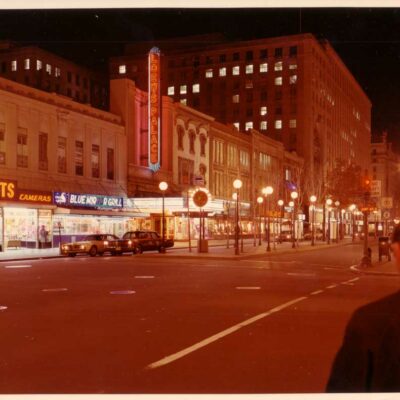

Understandably, the Peter family and the South as a whole was outraged. Confederate president Jefferson Davis even wrote to President Lincoln regarding the event. What little solace that could be brought to the families came when the bodies were reburied in Oak Hill Cemetery in Georgetown.