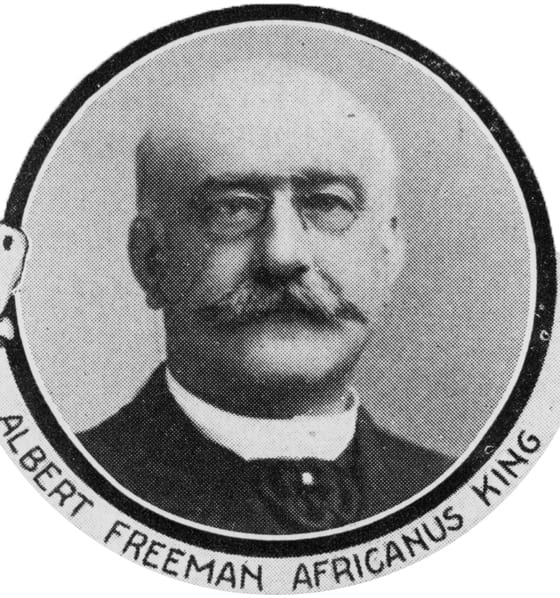

A Washington doctor with an interesting name was among the first to suggest a link between mosquitos and malaria. Meet Albert Freeman Africanus King.

Dr. A.F.A. King was a professor of obstetrics at Columbian University, precursor to the present-day George Washington University. The malaria-mosquito connection was his top scientific acheivement. But history remembers his presence at another key American moment (more on that later).

A Giant Mosquito Net

King delivered a talk to the Philosophical Society of Washington on February 10, 1882. “Insects and Disease—Mosquitoes and Malaria” outlined 19 reasons to suspect the mosquito as the source of malarial infections. A version of his lecture was also published in Popular Science Monthly in September 1883.

One of King’s anti-malaria suggestions gained the most attention:

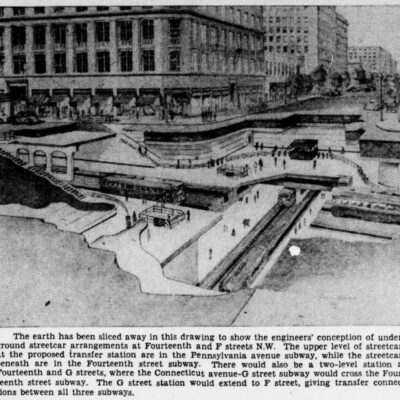

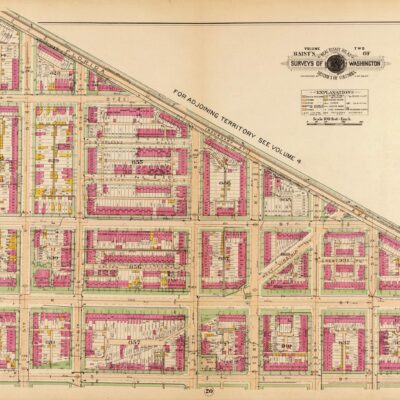

Municipal protection by groves of trees (pines, cedars, or eucalyptus) planted between cities and the sources of of malaria and mosquitoes, together with cordons of electric or other lights, between said groves and the marsh, the lights to be arranged as fly-traps for the retentions and destruction of such winged insects as may be thus secured.

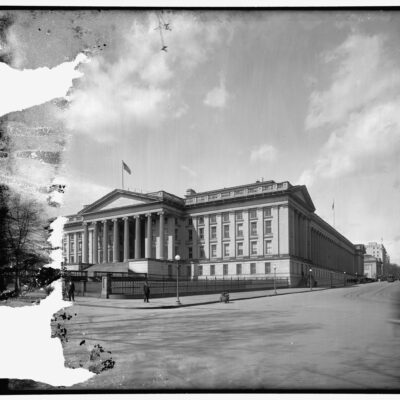

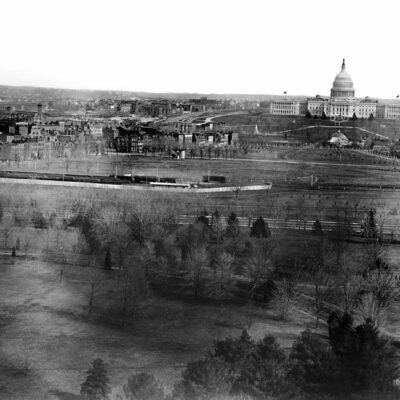

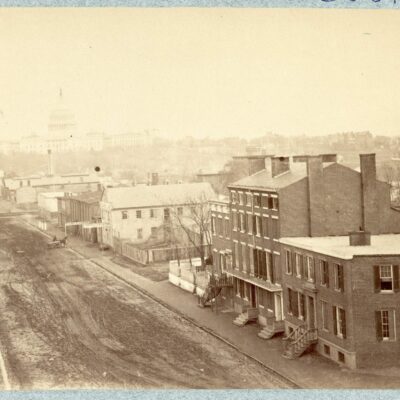

With relation to the city of Washington, it was suggested that the Washington Monument would afford a good opportunity (by placing illuminated fly-traps at different elevations on its exterior) for ascertaining the height at which mosquitos fly, or are brought by the wind from the adjacent Potomac flats.

Put simply, King advocated a giant wire screen around D.C. — something as tall as the District’s tallest point.

Of course, science eventually confirmed King’s basic premise on the cause of malaria. Several other researchers made the link within months of the Washington doctor. But that mosquito netting around D.C. never materialized.

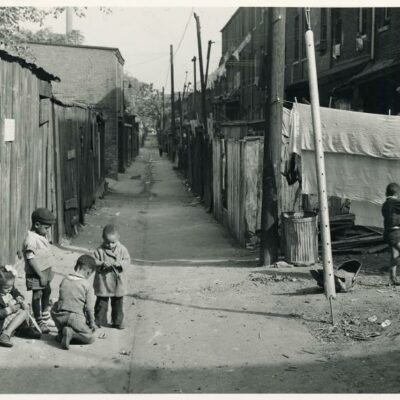

It’s also worth noting that Dr. King was totally wrong on some other theories. He believed that skin color played a factor in contracting malaria:

Crude, simple, and at first sight ludicrous as it may appear, it is nevertheless worthy of consideration that the negro is black, and, in the absence of moonlight or artificial illumination, can not at night be so readily seen as a white man; he may therefore on this account escape the sight, and consequently the bite, of the mosquito. The deep tint of his skin possibly constitutes a “protective coloring,” such as in many other species affords a defense against natural enemies.

So… that was wrong. A few of Dr. A.F.A. King’s ideas from the 1880s appear a bit racisty today. But he had the right idea on the crux of the matter. Mosquitos do indeed transmit malaria.

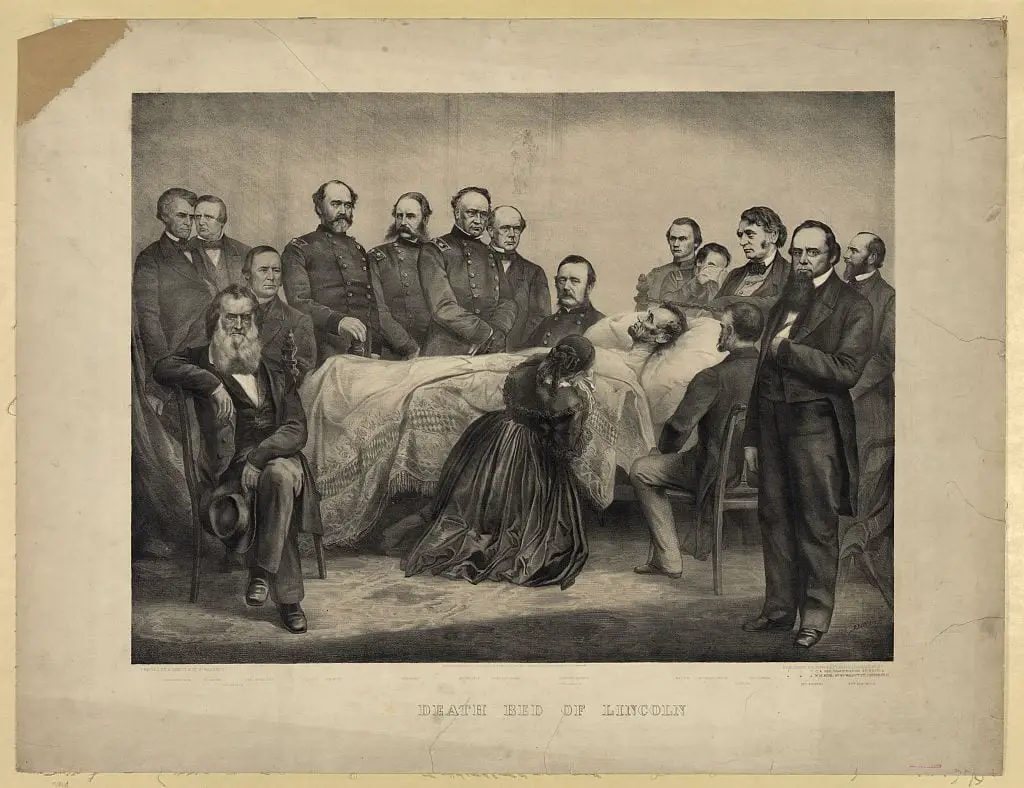

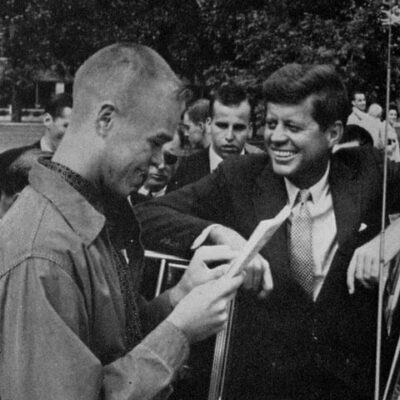

At Lincoln’s Death Bed

Several years before he studied malaria, Dr. King was known for tending to President Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre. King was one of a handful of physicians in the audience on April 14, 1865. When Lincoln was shot, King was the second or third doctor to arrive at his side. He helped carry the president across 10th Street and remained at his bedside.