In 1860, Japan emerged from over 200 years of self-imposed isolation and sent its first-ever diplomatic envoys overseas to ratify a landmark treaty with the United States. This pioneering group of early diplomats fascinated the American public and laid the foundations for an enduring alliance between the two nations.

Japan’s Sakoku Policy of National Seclusion

For over two centuries during the Edo Period, Japan adopted an official policy of national isolationism known as sakoku – meaning “locked country” or “chained country”. Under this doctrine, Japan severely restricted trade and contact with foreign powers from the early 1600s until the mid-19th century.

The sakoku policy was instituted by the ruling Tokugawa Shogunate in order to limit the influence of Christianity in Japan after seeing its effects in the Spanish colonization of the Philippines. All inbound foreign trade was restricted to select Chinese and Dutch merchants confined to the man-made island of Dejima near Nagasaki. Japanese people were forbidden from traveling abroad or returning if they left.

This national isolation allowed the Tokugawa Shogunate to consolidate their control over the country for over 200 years. However, by the 19th century, Japan had fallen behind the Western world technologically and economically. The arrival of American Naval Commodore Matthew Perry’s fleet of “Black Ships” in Tokyo Harbor in 1853 decisively ended Japan’s era of seclusion.

Commodore Perry and Japan’s Forced Opening

With the threat of force, Perry demanded Japan open itself to Western trade. In 1854, the Japanese signed the Convention of Kanagawa granting access to American vessels. Soon after, similar trade agreements were signed with other foreign powers.

In July 1858, the United States and Japan signed the Treaty of Amity and Commerce, officially establishing diplomatic relations after centuries of isolationism. However, the treaty still required formal ratification.

Just two years after Commodore Perry’s intrusion, the Japanese rulers took the unprecedented move to send their highest-ranking ambassadors on the two-month journey to Washington D.C. This embassy would finally ratify the commercial treaty, symbolically ending the Edo Period policy of national seclusion for good.

Historic Journey to Washington

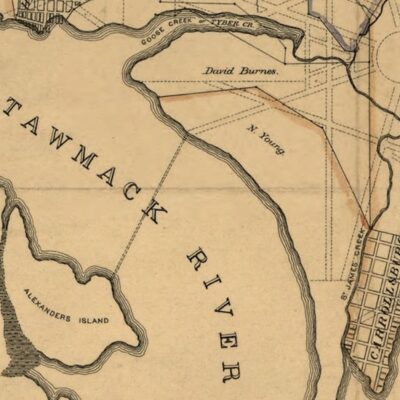

In February 1860, the Japanese embassy embarked on a monumental journey halfway around the world from Yokohama to Washington D.C. The delegation consisted of around 70 dignitaries, servants, and attendants.

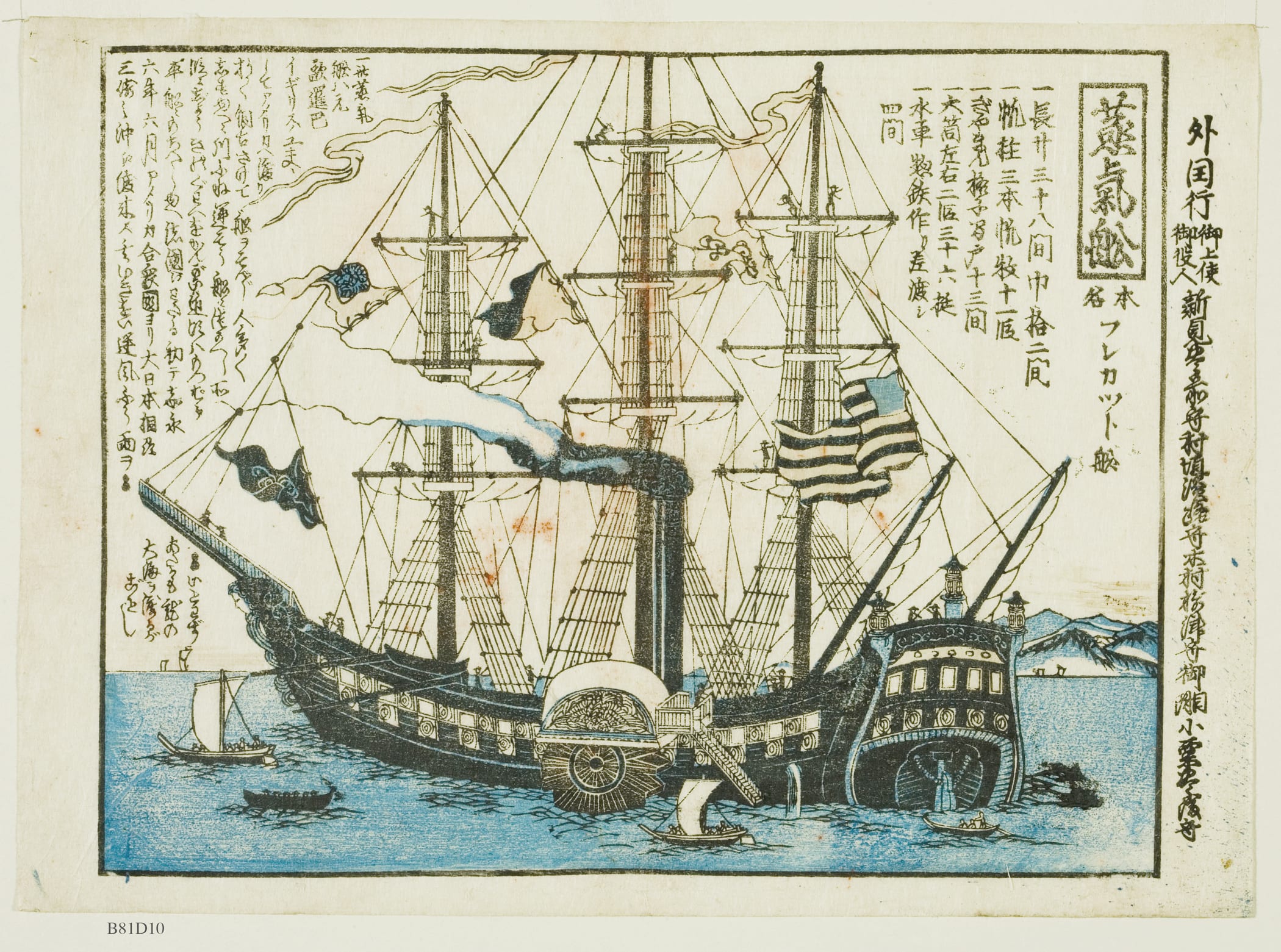

They set sail on an American steam frigate, the USS Powhatan, accompanied by the Kanrin Maru – the first Japanese ship ever to cross the Pacific. As described by the Japanese consulate, “It was a long and perilous voyage, sailing 37 days across the Pacific.”

Braving intense storms, the ships charted a course due east towards California. As recounted by the U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command, the Powhatan faced “vicious headwinds” and “mountainous seas” that smashed stoves and flooded the upper decks.

Upon arriving in San Francisco after over 5 weeks at sea, the embassy then crossed the Isthmus of Panama by railroad, which had just been completed in 1855. They then sailed to Cuba and up the Eastern Seaboard to Washington.

The delegation brought a massive amount of gifts and supplies for their journey totaling over 80 tons, requiring 30 ox carts in Panama alone. One crate reportedly contained an intricately crafted black-lacquered gift shelf to offer President Buchanan. Their huge amount of cargo demonstrated Japan’s enormous effort and commitment in sending this diplomatic mission halfway around the world to establish ties with America.

The arduous six-week sea voyage and overland railroad crossing of Panama carried real hazards in those times. However, the embassy braved their treacherous passage in order to finalize the historic commercial treaty that would end over 200 years of isolation and open a new era of engagement with the Western world for Japan.

A Glimpse Into Ancient Japan: America’s Fascination

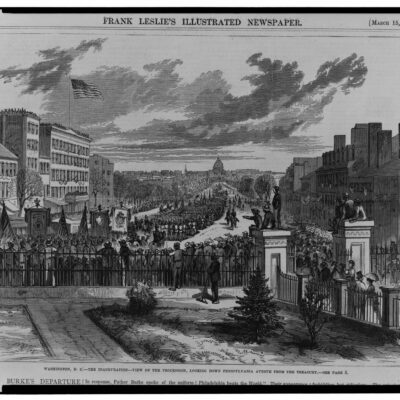

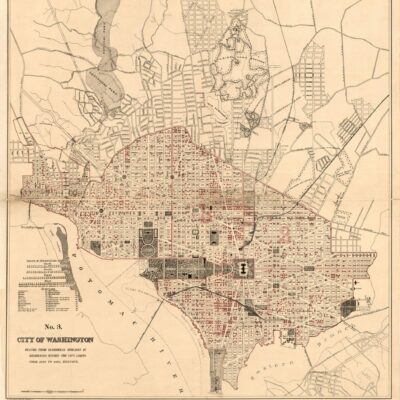

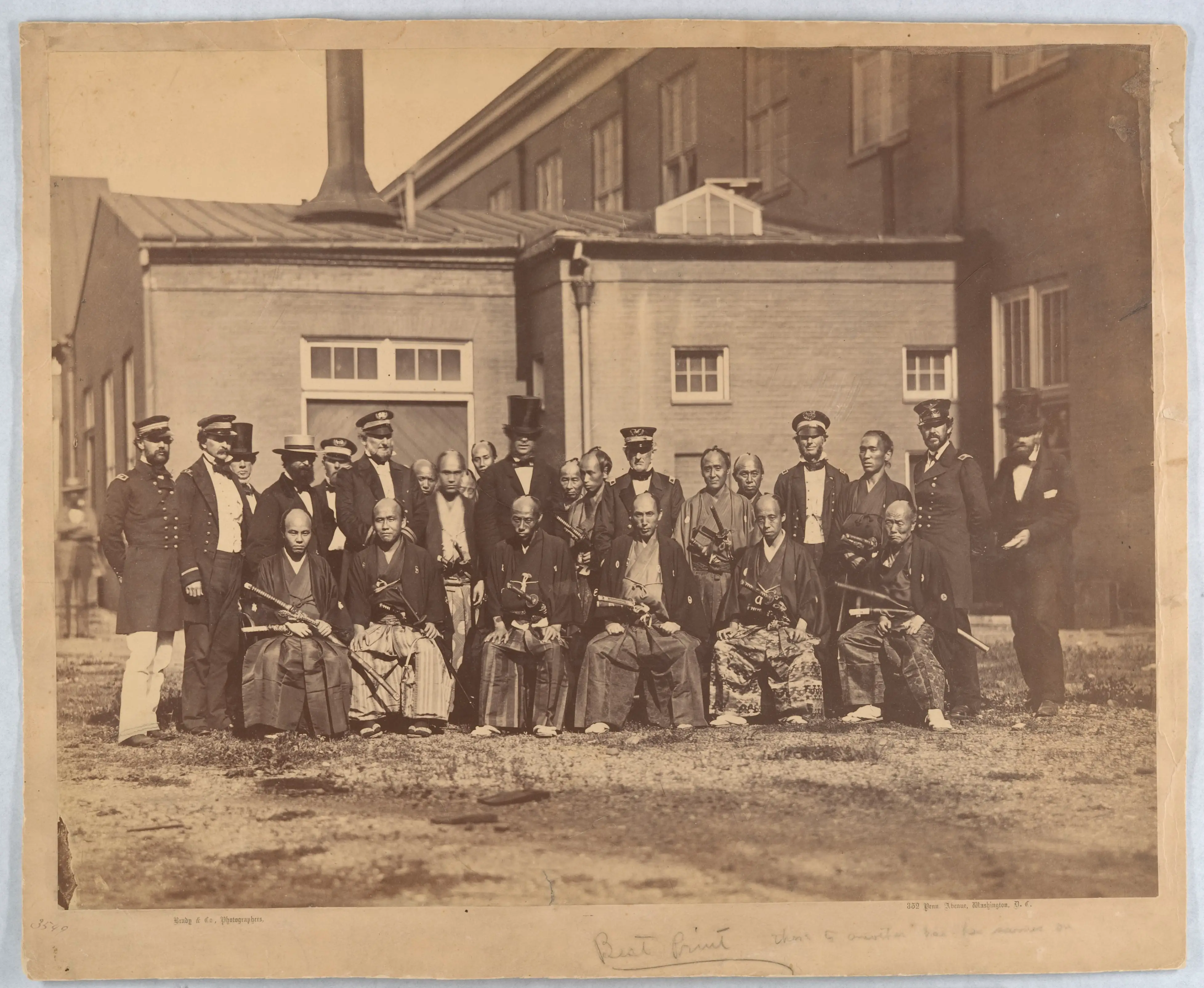

The Japanese delegation’s arrival at the Washington Navy Yard on May 14th, 1860 garnered immense nationwide attention and intrigue. One historical account in the Baltimore Sun described: “5,000 cheering spectators; an additional 20,000 climbed trees and hung out of windows for a look as the visitors’ procession reached Willard’s Hotel.”

The American public was utterly fascinated by the exotic foreign diplomats. Huge crowds turned out wherever the embassy traveled over the next few weeks, eager to catch a glimpse of the elaborately dressed ambassadors with their distinctive topknot hairstyles and prominent swords.

Onlookers marveled at the strange and elaborate nature of their wide-sleeved silk robes, called kamishimo, often embellished with family crests. The striking clothing stood in stark contrast to the suits and dresses of 19th century America. Even the youngest attendants and servants wore ornate garb, adding to the spectacle.

The embassy’s swords and daggers, in particular, captivated the public’s imagination. One newspaper account from the time described their “remarkable Samurai swords” as objects of “interest and curiosity.” While largely ceremonial, the weapons symbolized the warrior prestige still associated with the samurai class in feudal Japan.

The embassy’s exotic gifts, transported in over 80 tons of crates and boxes, also attracted much fascination. Crowds gathered outside their hotel, hoping to catch a glimpse of the elaborate items carried halfway across the world. Delicate silk fabrics, porcelain vases, and lacquered boxes were later put on display, dazzling Americans with Japanese artistry.

Their unusual hairstyle, oiled and swept up into a topknot or chonmage, became an object of popular curiosity. The style indicated their elite status, allowing the public to distinguish the diplomats from servants with shaved pates. Mischievous American children would often yell up to the hotel windows, jokingly asking for a lock of the envoys’ hair.

One aspect of the embassy that enthralled American women were the elite young interpreters, especially 17-year-old Tateishi Onojiro, who became known as “Tommy.” Newspapers described admiring crowds chanting “Tommy, Tommy” outside the hotel, charmed by his friendliness.

As the embassy toured cities like New York, massive crowds lined the streets hoping for a glance. Walt Whitman captured the public fascination, writing a poem to commemorate their Broadway parade that drew over 500,000 cheering onlookers.

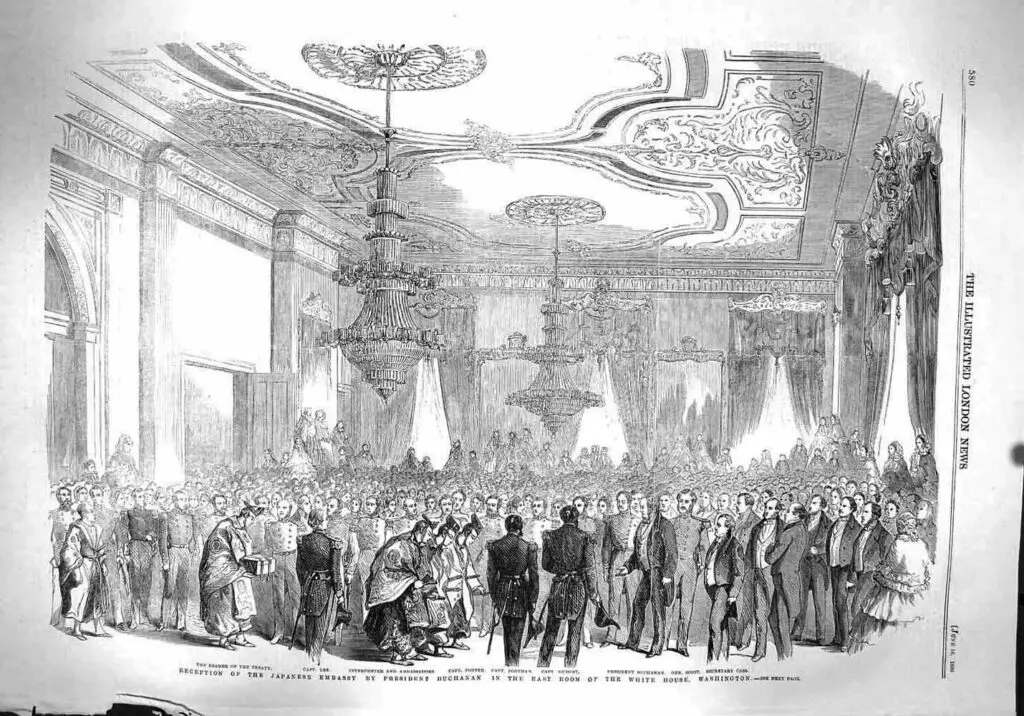

The lavish receptions held for the diplomats also became a social spectacle among American elites. In Washington, Congress granted $50,000 to entertain the delegation, holding numerous balls and banquets in their honor.

Americans were not only intrigued by the striking appearance of the exotic foreigners, but also by what they represented – the mystique of a Japan unseen by Western eyes for over 200 years. Even while touring modern 19th century cities, the samurai evoked images of a land still steeped in ancient traditions, rituals, and imperial culture.

The embassy ignited an enduring fascination with Japanese aesthetics and customs. Their mere presence seemed to transport Americans to a distant and mysterious land they had only imagined through stories and art. For a public with limited perspective of the outside world, the embassy exposed them to a civilization remarkably different from their own.

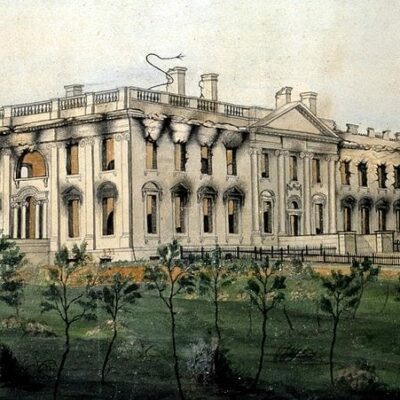

Ceremony at The White House

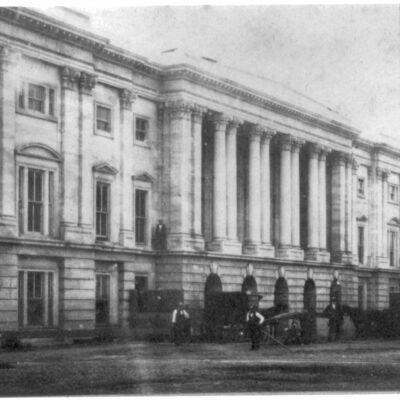

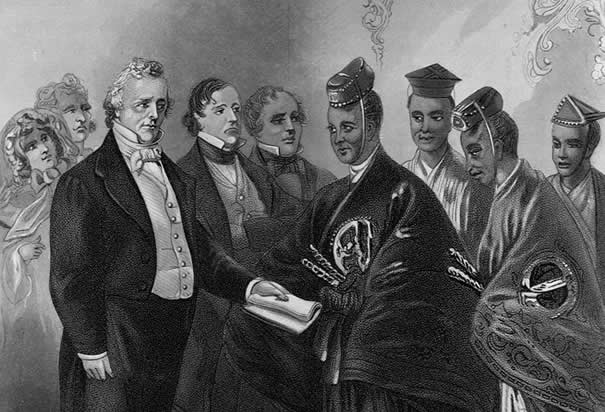

On May 17th, 1860, President James Buchanan formally received the Japanese envoys with immense pomp and circumstance in the East Room of the White House. The event attracted hundreds of dignitaries packed into the room, eager for a view of the historic occasion.

As mentioned by the White House Historical Association, “Vice-Ambassador Muragaki Norimasa remembered Buchanan as ‘a silver-haired man’ with ‘a most genial manner without losing noble dignity.'”

The Japanese entered slowly and solemnly in full regalia before taking their positions. Ambassador Shinmi Masaoki then stepped forward to present his diplomatic credentials and read aloud a letter from the Emperor expressing desire for “lasting peace and friendship between the two countries.”

President Buchanan warmly welcomed the embassy, promising faithful execution of the new Treaty of Amity and Commerce. As quoted by the U.S. Diplomacy Center, he proclaimed: “I trust that this will be the harbinger of perpetual peace and friendship between the two countries.”

His speech helped pave the way for expanded economic ties and diplomatic engagement after centuries of Japanese isolationism under the Tokugawa Shogunate.

At an elaborate banquet later honoring the embassy, Buchanan gifted the dignitaries with commemorative gold medals specially minted to mark the historic occasion. The lavish reception initiated a week of ceremonies, tours, and celebrations cementing official diplomatic relations between the U.S. and Japan.

Enduring Legacy

The pioneering 1860 Japanese embassy laid crucial groundwork for the modern-day alliance between Japan and the United States that has strengthened immensely over 160 years.

While largely symbolic, the bold diplomatic mission was transformational in initiating engagement with America in a new era of Japanese openness to the world. Their six-week Pacific crossing presaged an age of open trade and diplomacy.

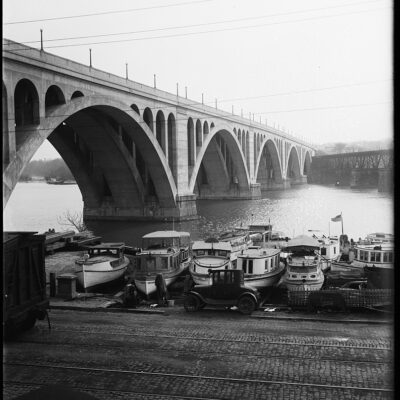

The ratified Treaty of Amity and Commerce started an enduring legacy of economic and political ties. In the decades after, the U.S. became a major trading partner as Japanese exports flowed through its ports. A Japanese embassy was later established in Washington in 1872.

By crossing the Pacific, the intrepid Japanese diplomats pioneered relations between Japan and the Western world after centuries confined by the sakoku policy of isolationism. Their visit ignited an American fascination with Japanese culture that endures today.

The 1860 embassy stands as a shining historic milestone in the enduring bond between the two nations. 160 years later, the same spirit of friendship and exchange continues between Japan and the United States.