This is the first guest post by GoDCer Tim. Given that we have “ghosts” in our name and with today being Halloween, it’s appropriate to have a post about the paranormal. Also, don’t forget to check out Tim’s recently released book on Amazon about haunted Capitol Hill.

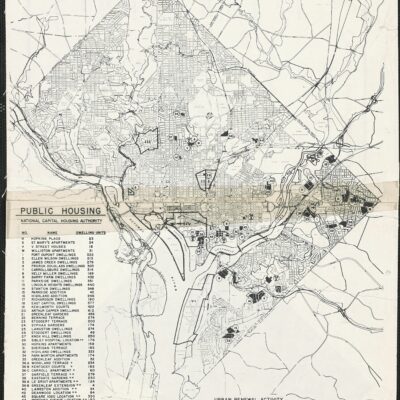

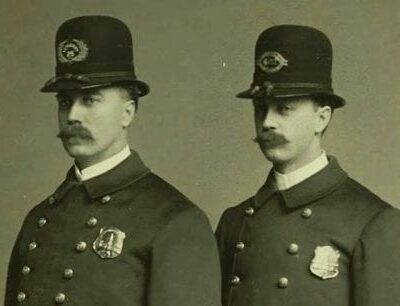

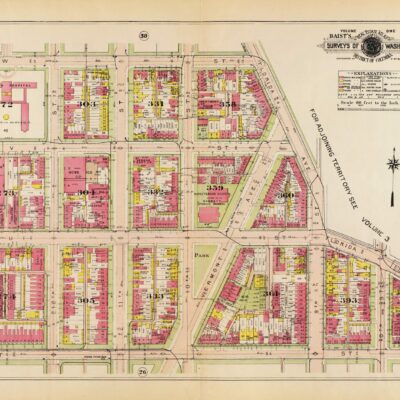

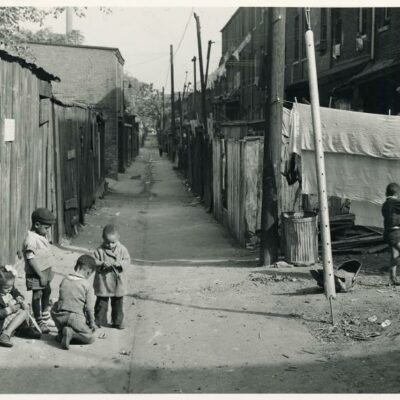

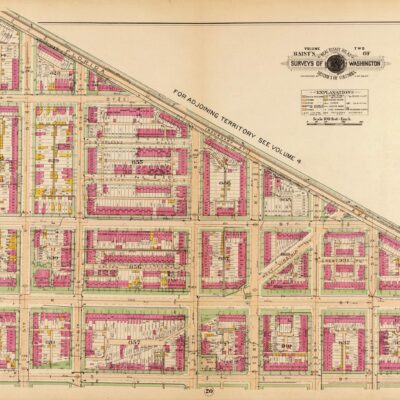

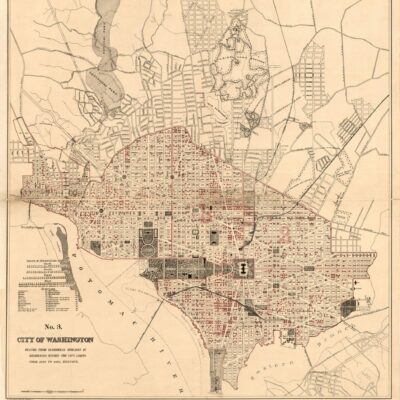

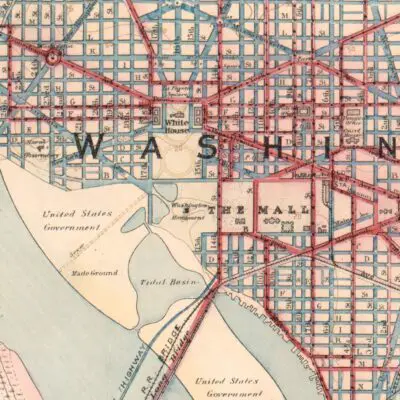

On Capitol Hill a few blocks from the Eastern Market Metro Station is a fully functioning relic of a time gone by, the Metropolitan Police Department’s First District Substation. MPD traces its origins back to the Civil War, when rapid government expansion, an incoming horde of unscrupulous opportunists and not a few drunken soldiers made the existing system of a fifteen-man auxiliary watch untenable.

Today, MPD is a thoroughly modern crime-fighting organization, but the 1D-1 Substation hearkens back to a different time—when patrolmen walked their beat, checking in via call boxes still visible on many city streets, and used whistles to call for backup. Local residents are largely familiar with it as the place to go to get parking permits for out-of-town residents, and a step inside gives a whiff of Joe Friday. It’s a throwback, a historic building still in active use, not gussied up with new wood paneling, with an actual desk officer, slightly bored and almost always helpful, there to answer questions.

Ghosts and cops have a long, symbiotic history together. In days past, and today to an extent, they would often be the only two classes of beings walking around deserted city streets at two o’clock in the morning. Many a ghost has been sighted by a police officer, and even when the ghost appears to someone else, reporters instantly turn to the officer on the local beat for confirmation. More often than not, the cop is a believer and can regale even cynical reporters with prior instances of apparitions, streets he won’t walk down and other dark doings of the night.

So it was no surprise a few years ago when a local MPD officer (who has asked to remain nameless) told a tale of a mysterious occurrence at the substation. It happened, as these tales so often do, on a dark and stormy night, when the officer was on desk duty at the front door. The station was equipped with a closed-circuit TV camera, naturally, and just when the officer felt that he was losing the long war against drowsiness, he noticed another officer on the TV, which was odd, as he was mortally certain that he was alone in the building.

It was hard to see, but the phantom officer didn’t look like any of the police officers then assigned at the station. What’s more, he was wearing an anachronistic jacket and a long coat, seemingly dripping with rain. Via camera, our confused and slightly apprehensive officer tracked the mysterious being as he headed out a side entrance and disappeared into the gloom. A search was made: the side door was still locked and showed no sign of being opened recently, and there were no wet floors that you might expect from a dripping coat. Playing back the tape revealed only the ordinary quiet of a virtually empty police station in the wee hours of the morning.

The officer had no explanation of the tale and has often managed to convince himself that it was all in his head. But the question lingers: who was the phantom officer?

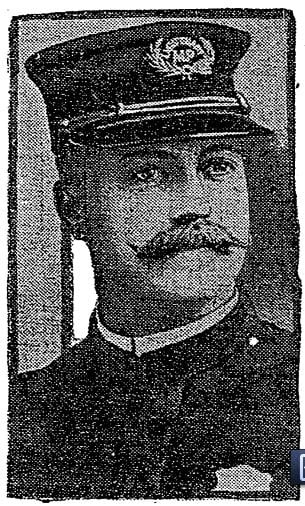

Well, there’s certainly a candidate that fits the bill. On the evening of March 5, 1909, at 7:45 p.m., policeman John W. Collier boldly walked into what was then the Fifth Precinct station house and shot the precinct commander, Captain William H. Mathews, five times, emptying the last three rounds directly into his head. Captain Mathews’s deputy, Lieutenant J.L. Sprinkle (longtime favorite of Ghosts of DC readers!), and two other officers instantly wrestled Collier to the ground, but the damage was done. A doctor was summoned, but he could only confirm what the officers already knew: Captain Mathews had been ruthlessly killed without warning by one of his own officers.

Collier offered no resistance nor defense. “I shot him, all right, and I’ll give my reasons later. I was rational and sober, and there was nothing wrong with me,” he calmly told Lieutenant Sprinkle as he was taken to the District Jail.

In the coming days, some semblance of a picture gradually emerged of the events of the fifth and before. Captain Mathews was known as a by-the-book cop, a “strict disciplinarian,” as the Washington Times put it, but he was later accused by defense attorneys of being “quarrelsome, vindictive, and violent.” Collier was a slacker who had been before the trial board (a disciplinary board for police officers) nine or ten times. His mother defended her son but offered what was perhaps not the best defense: he felt he was being persecuted for being late.

On the day of the murder, Collier was supposed to go on duty at midnight. A 4:00 p.m., he called in sick. The captain had had enough and told him to come in to the station so that he could see if Collier was sick or not. Just past 7:00 p.m., Mathews received another phone call from Collier that made him turn red and slam “the receiver on the hook with such vigor that the telephone nearly overturned.” Collier showed up about half an hour later, talked to no one and walked by the other officers, who nudged one another and whispered, “He’ll get his when the captain sees him.” Seconds later, the shots rang out.

Collier testified several months later that this was a case of self-defense. He said that the captain had told him in the telephone exchange, “I wouldn’t give 15 cents for your chances when you come into the office.” Upon his arrival, the captain told him that his goose was cooked, to which Collier replied, “I think you have another thing coming, Captain.” Then, according to Collier, Captain Mathews muttered, “Damn you, I’ll get you for that,” and reached toward his hip pocket. Thinking that Mathews was going to shoot first, Collier fired and killed him.

The trial was a particularly tense affair, as at one point the defense attorney took a swing at the district attorney. The assistant district attorney jumped between them and got a punch in the face for his efforts. The fight was then broken up by a police officer and, believe or not, the defendant. Perhaps that swung the jury a bit, or perhaps they found his story plausible, as Collier was found guilty of only manslaughter and was sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

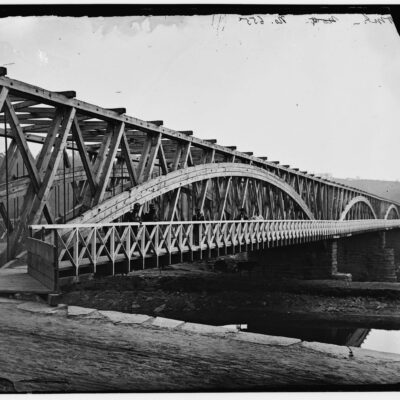

Is Captain Mathews the mysterious ghost seen on the video cameras? Who knows, but to answer the inevitable question, it was cold and clear out on the night he was murdered, although Washington was recovering from a snowstorm so intense the night before that it drove President Taft’s inauguration indoors. So perhaps it was melting snow on the overcoat?