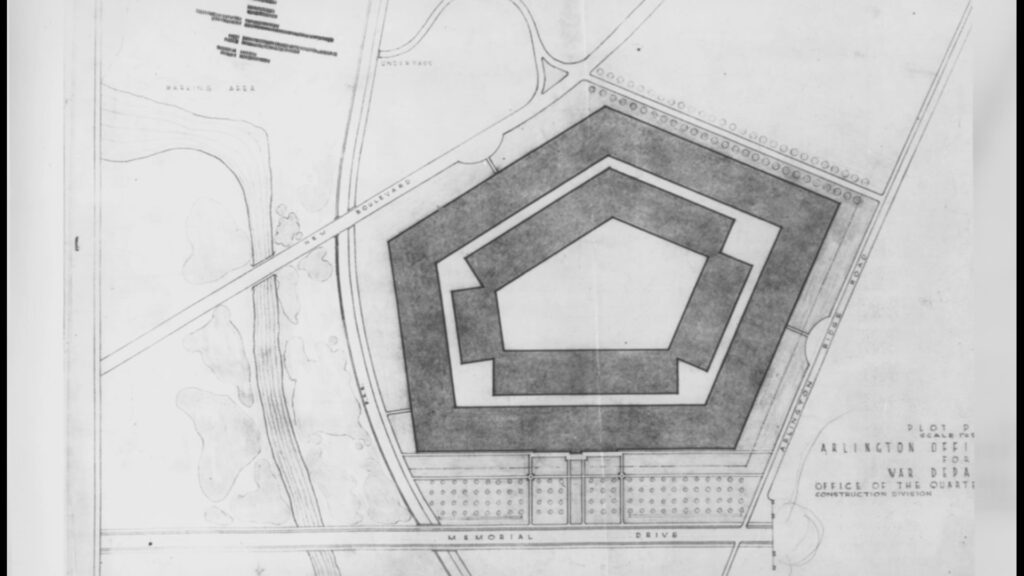

Most people assume the Pentagon’s famous five-sided shape was some grand symbolic choice. Maybe it represented the five branches of military service, or embodied geometric perfection for defense planning. The truth is far more mundane and yet more fascinating: the world’s most recognizable military building got its shape because of farm roads in Arlington, Virginia.

On Thursday, July 17, 1941, General Brehon B. Somervell summoned his construction team to address the War Department’s critical space crisis. Somervell gave Lt. Col. Hugh J. Casey, Chief of the Design Section, and chief consulting architect George Bergstrom what seemed like an impossible assignment: design basic plans for a fireproof, air-conditioned office building to house 40,000 people. The deadline: 9:00 a.m. Monday morning, July 21.

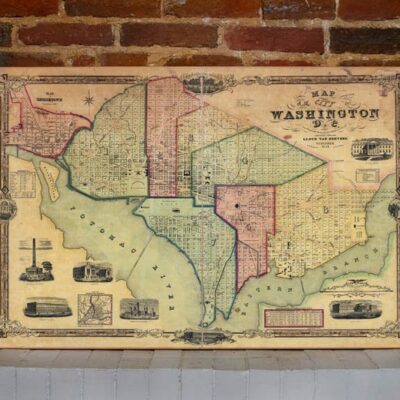

The urgency was real. By summer 1941, the War Department had grown explosively to 24,000 military and civilian employees scattered across 17 buildings in the Washington area. The largest, the Munitions Building, contained 779,000 square feet but couldn’t accommodate the expanding staff. Officials estimated they needed an additional 734,000 square feet of office space immediately, with a 25 percent personnel increase expected by January 1942.

The First Site: Hoover Airport and the Pentagon Shape

Somervell initially proposed building on land that included the old Washington-Hoover Airport site along the Potomac River. But Brig. Gen. Eugene Reybold, soon to become Chief of Engineers, inspected the proposed construction site on the Potomac flood plain and decided it might not be practical to build there. He recommended moving the location north and west to higher ground at Arlington Experimental Farms.

This site change would prove crucial to architectural history. The Arlington Farms tract had an irregular pentagonal boundary created by surrounding roads and property lines. The government had established this experimental farm in 1900 on 400 acres transferred from the War Department to the Department of Agriculture. In 1940, Congress returned control of Arlington Farms to the War Department.

Casey and Bergstrom recognized that a building of unprecedented size would require efficient design for pedestrian movement. According to later accounts, Bergstrom deserves primary credit for the pentagonal design concept. The architects considered square, rectangular, and octagonal layouts before settling on the pentagon. They fitted their proposed building to the Arlington Farms site, creating a structure with five sides that matched the property’s irregular boundary.

The weekend team worked feverishly from Friday night to Sunday night to complete preliminary plans and cost estimates. By Monday morning, July 21, they presented Somervell with designs for a building containing approximately 4 million square feet organized as concentric pentagonal rings connected by radial corridors.

Washington’s War Crisis

The context was urgent. Three weeks earlier, Hitler had invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had already declared a national emergency on May 27. Washington was consumed by mobilization efforts as the Army planned a tenfold increase in strength.

On July 17, the same day as Somervell’s meeting, Representative Clifton A. Woodrum of Virginia, chairman of the House Appropriations subcommittee handling construction funds, suggested the War Department develop a comprehensive solution rather than continue piecemeal building additions. Somervell took this as encouragement to propose something permanent and substantial.

That afternoon, Generals Marshall and Moore and Under Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson approved the plan. The next morning, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson reviewed it and, though initially skeptical, gave his concurrence.

Roosevelt Intervenes and Changes Everything

The proposal faced immediate opposition. Gilmore D. Clarke, Chairman of the Commission on Fine Arts, and Frederic A. Delano, Chairman of the National Capital Park and Planning Commission, objected to the Arlington Farms location. They argued it would damage the ceremonial approach to Washington and interfere with views from Arlington National Cemetery toward the Lincoln Memorial.

Clarke gained access to President Roosevelt and expressed the Fine Arts Commission’s bitter opposition to the site. According to Clarke’s later account, Roosevelt agreed with the criticism and promised to reconsider the location.

At a press conference on August 19, Roosevelt announced his objection to the Arlington Farms site, comparing it to his role in placing temporary buildings on the Mall during World War I, which he called “a crime for which I should be kept out of Heaven.” He spoke of not wanting to “spoil the plan of the National Capital” again.

On August 26, Roosevelt summoned key officials to his office and made clear his preference for the southerly depot site. On August 29, he personally toured both locations with Somervell, Clarke, and Budget Director Harold Smith. Contemporary accounts indicate that when Somervell continued to argue for the Arlington Farms location, Roosevelt overruled his objections and selected the depot site.

Roosevelt also directed that the building be scaled back from 40,000 to 20,000 employees. However, the final structure would ultimately house far more than this reduced target.

The Accidental Icon

Here’s where the story gets really interesting. The original rationale for the pentagonal design had disappeared with Roosevelt’s site change. The building would no longer be constructed on the irregularly shaped Arlington Farms property that had suggested the five-sided configuration.

Yet the architects retained the pentagon design for the new location. There was no time to start over with the design process, and the pentagonal arrangement offered advantages they had begun to recognize. The shape approaching a circle would provide the greatest usable area with the shortest internal walking distances. Architects later calculated that the pentagonal design reduced walking distances compared to rectangular alternatives of similar capacity.

Construction began on September 11, 1941, just three months after Somervell’s impossible weekend assignment. The building proceeded with remarkable speed, with sections occupied as they were completed. By January 1943, the structure contained approximately 6.5 million square feet of floor space across five stories, making it the world’s largest office building.

Pentagon Legends

The building quickly generated its own mythology. A 1944 War Department publication noted that the Pentagon had inspired “humorous stories on a scale to rival the jeep or the Model T Ford car.”

Among the most enduring legends: a Western Union messenger boy supposedly entered the building on Friday and emerged Monday as a lieutenant colonel. Another tale describes a repairman sent to fix a ceiling connection who disappeared through a trap door and didn’t reappear for days, finally staggering onto an escalator where General Marshall happened to be riding.

While these stories became part of Pentagon folklore, the building’s actual scale was impressive enough. The structure covers 29 acres with 17.5 miles of corridors, yet the pentagonal design allows travel between any two points in approximately seven to eight minutes.

We dug up a fascinating truth: when you see the Pentagon today, you’re looking at a building whose most distinctive feature originated from the practical constraints of an experimental farm’s property boundaries. The shape that makes it among the most recognizable buildings worldwide exists because Arlington Farms happened to be bounded by roads and property lines forming an irregular pentagon.

The architects kept this configuration when Roosevelt moved the project to a completely different site, initially due to time constraints but ultimately because the pentagonal arrangement offered functional advantages for such a massive structure. What began as accommodation to existing agricultural boundaries became an architectural icon representing American military power.

The next time you drive past on Interstate 395 or see it in movies, remember: this symbol got its famous silhouette from something as mundane as where farm roads were laid out decades earlier. In Washington, even the most intentional-looking designs sometimes emerge from the most practical constraints.

![Night view in rain [of Capitol] taken from steps [Neptune Plaza] of Library of Congress](https://ghostsofdc.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2013/12/3b42062u-400x400.jpg)