This is one of the more interesting personal stories that we’ve uncovered.

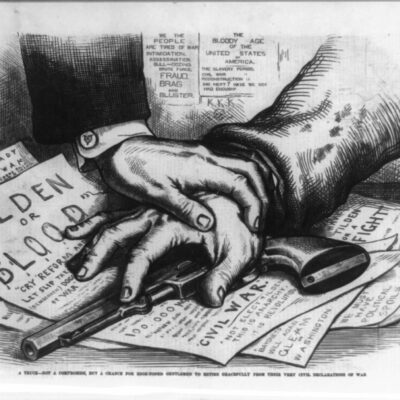

For a while now, we’ve heard stories about Ulysses Grant being arrested for riding his horse too fast in the city. This is amusing on two accounts, the first being the President driving a horse and buggy alone on the streets of Washington. The second, that he was actually stopped and arrested for speeding. Clearly, we wouldn’t see this today, even though, technically, POTUS’ motorcade probably doesn’t obey the speed limit signs in D.C.

Ulysses Grant arrested for speeding

The most informative article about the incident was one that we found in The Washington Post, written by J. LeCount Chestnut on November 7th, 1925.

William West is the horseman who once arrested a president. He forced President Ulysses S. Grant to go with him to the police station where he booked the chief executive on charges of speeding. Grant was driving his favorite team of horses at what West thought was excessive speed. He ordered the president to stop, chased him down, gave him a lecture in approved modern traffic cop style, and then arrested him.

Grant and West became solid pals after the incident, and in one of their frequent chats West informed the president that he, too, was a speed maniac, and that while off duty he had been arrested more than 20 times for speeding. West owned a stable of fine horses that at once attracted Grant’s admiration, and provided for the two men a strong bond of common interest.

…

The day before Grant’s arrest a woman with a 6-year-old child had been seriously injured at West’s corner by a driver of fast horses. Washington, after a series of such accidents, was conducting the same campaign against “reckless driving” of horses that modern metropolitan cities are engaging in today to check auto speeding. Grant had chosen the wrong time to dash by the corner of 13th and M Sts. his team thundering along at a furious pace. West shouted, the president’s team was brought to a standstill, and West approached him. “Well, officer, what do you want with me?” Grant asked.

“Mr. President,” was the reply, ” I want to tell you that you were violating the law by driving at reckless speed. Your fast driving, sir, has set the example for a lot of other gentlemen. It is endangering the lives of the people who have to cross the street in this locality. Only this evening a lady was knocked down by one of the racing teams.”

“I am very sorry,” said President Grant, “and I’ll promise that hereafter I will hold my team down to the regulation speed. Is the lady who was run down seriously hurt?”

But the very next day, however, the good intentions were forgotten, and General Grant came racing down 13th St. fast as ever. When hailed, he turned into M St. and was almost at 14th before he could stop. As West approached, Grant said, “Do you think, officer, that I was violating the speed laws?”

“I certainly do, Mr. President,” answered West, not a bit softened by the president’s query. “I cautioned you yesterday, Mr. President, about fast driving, and you said, sir, that it would not occur again. I am very sorry, Mr. President, to have to do it, for you are the nation’s chief executive, but my duty is plain, sir: I shall have to place you under arrest!”

Part of me is a little skeptical that it went down exactly like this, but nevertheless … the story continues.

At the request of the president, Officer West got into the executive’s carriage, sat beside him and drove to the station house. Grant left $20 collateral, which was forfeited.

After this incident President Grant and Officer West grew very friendly and spent frequently hours at a time chatting. Their love of horses was the great bond of sympathy. Strange to relate, West himself was an inveterate fast driver. He confessed that he had been arrested at least 25 times for speeding.

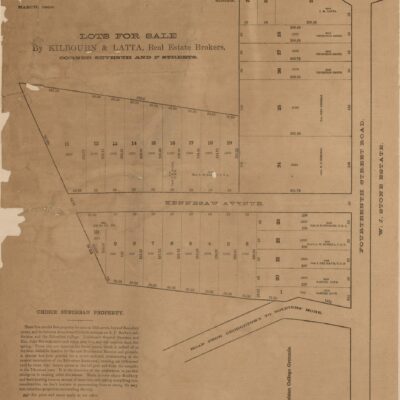

Old timers around Washington yet remember West’s remarkable horse, “Dan.” This animal was so trained that when his master had cornered an offender, he would seize the culprit by the coat with his great front teeth. As a rule, the horse was careful not to catch a man’s flesh, but if the offender offered resistance the great teeth would grasp flesh along with clothing. The pair were a familiar sight for years at 7th and U Sts. N. W., where they were stationed.

There are a couple facts in this story that are different in other stories, but what seems to be consistent though, is that Officer West did arrest and book Grant. We found another story stating that Grant was arrested in 1866 before he was in the White House, and this is also true.

Another time Ulysses Grant was arrested

He was arrested on April 11th, 1866 as well as July 1st for reckless driving. At the time, he was still a general in the U.S. Army. POTUS 18 had a penchant for speeding, so all three of these stories are true. The man liked to ride fast, and paid the price a few times.

Whatever the details are of this story, the fact is, President Grant was arrested just after the Civil War and Emancipation Proclamation by an African-American Washington policeman. That’s a terrific story and a great piece of trivia with which you can impress your history-loving friends.

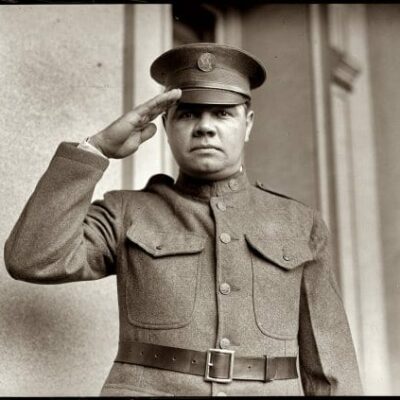

William West: African-American Policeman

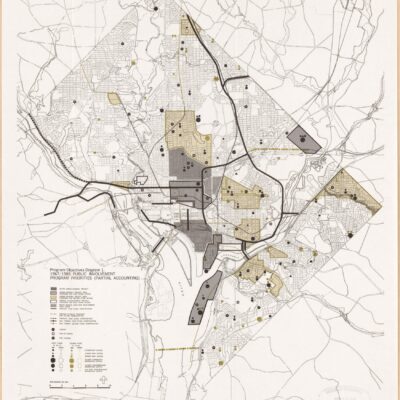

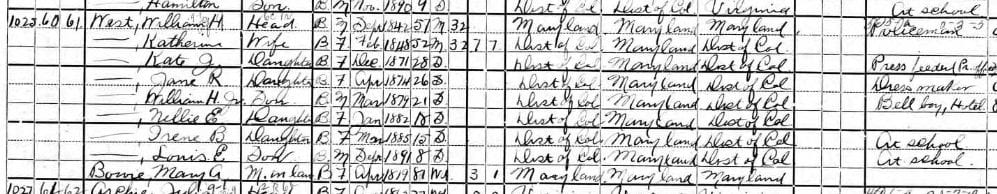

West was listed in the 1900 U.S. Census living at 1025 3rd St. NW, with his wife of 32 years, Katherine and their six children. Sadly, like so much of D.C., the building is gone.

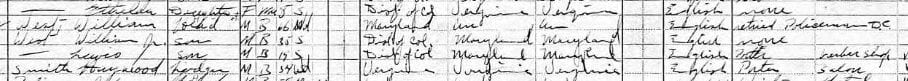

By 1910, his wife had passed away, and he was living at 424 New York Ave. NW with two sons and a lodger. This building also appears to be gone.

A decade or so after his encounter with President Grant, he had some trouble with the police force and was found guilty of neglecting his duties. Below is the article that we dug up from September 26th, 1884 in The Washington Post, detailing the account.

Officers William H. West and William H. White, of the police force, were tried last Wednesday before the trial board of the Metropolitan Police “for neglect of duty and indecently wrangling on political matters upon public streets.” The board found that the officers had stopped twenty or thirty minutes and entered into a conversation about matters not pertaining to their official duties and were also guilty of improper language on the public streets. Their sentence was a fine of $25 and in addition to be dismounted and transferred. … The rule referred to forbids officers from stopping and holding conversation with citizens while patrolling their beats.

If workplaces had this rule today, at least 75 percent of D.C. would be fined for surfing the web, checking Facebook, or chatting around the watercooler. Get back to work!

In later years, Officer West ran into some more trouble according to an in The Washington Post, printed on January 29th, 1898. West was accused and tried for not paying a certain debt of $40. He had borrowed the money from a Mrs. Terrell, a local money lender. At the time, it was common for them to prey on underpaid police officers (similar to those shady payday loans today) and charge exorbitant interest rates. The loan agreement had him paying 10% per month until it was paid off. He ended up paying $72 in 19 months and then ceased paying. Ultimately, the case was dismissed as the laws of D.C. exempted debtors from paying any interest rate deemed usurious.

He again shows up in the papers on June 30th, 1901 after being arrested for disorderly conduct in Mt. Vernon Square, following an argument.

Policeman William H. West, who has been before the trial board several times on charges of conduct unbecoming an officer, was arrested in Mount Vernon Square early last evening charged with disorderly conduct. At the First precinct station Lieut. Amiss directed that he be stripped of his badge and revolver and suspended. The lieutenant will make a report on the case to Maj. Sylvester this morning.

West is a negro, about fifty-eight years of age, and has been on the force many years. He gained notoriety soon after his appointment by arresting President U. S. Grant for riding horseback on a pavement. He is fond of blooded horses, and was a mounted policeman for several years.

He drove to the restaurant of Charles H. Dismer, at 708 K street northwest, early last evening. Lindsey Madre, a negro youth, was engaged to mind his team. When West returned to the vehicle he is said to have given Madre a tip of 5 cents. This started an argument, and Madre demanded more money for his services. The quarrel resulted in West and Madre going across the street to Mount Vernon Square, where their fight attracted the attention of the neighborhood. Policemen Hooper and McDonnell, of the First precinct, ran to the scene and arrest both men for disorderly conduct. They were released on $5 collateral each.

We dug up a little more on Lindsey Madre, who was born some time near 1873. In the 1910 city directory, he was listed as living at 807 Barry Pl., which is just west of Georgia Ave., near the McDonald’s and south of the baseball field.

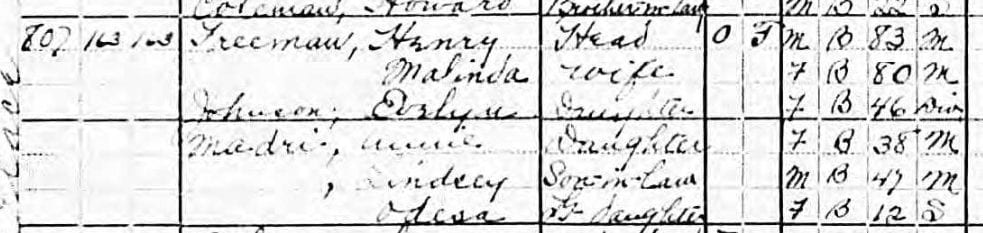

In the 1920 U.S. Census, he’s still listed at the same address with the occupation of bootblack (i.e., shoe shiner). He was living with his wife Annie and daughter, Odesa under the roof of his in-laws, the Freemans.