This is the first guest post by Roger. Check out his blog Forgotten Stories for some excellent lost history.

Philemon T. Herbert was a crooked lawyer, a card shark, frequented brothels, and stood accused of attacking a political rival with a knife. In other words, he fit right in with the rough and tumble environment of California in the early 1850s, so much so that the good voters of that state sent him to Congress as a Representative from the vast Mariposa district south of Sacramento.

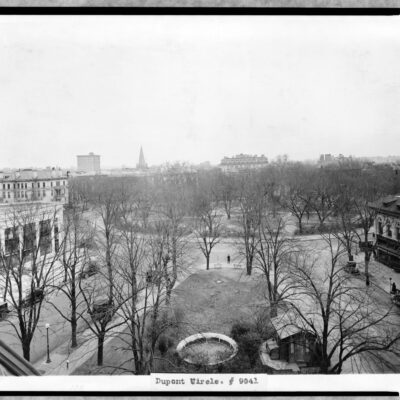

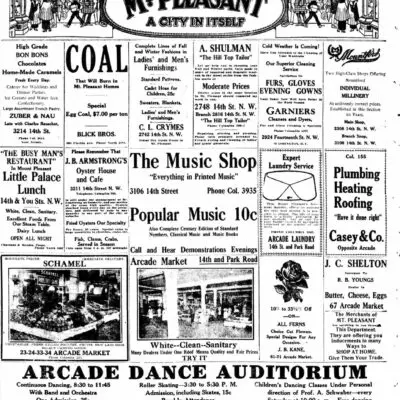

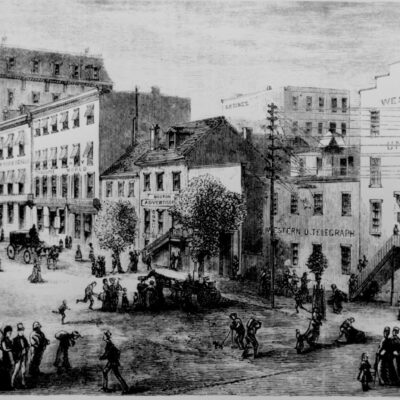

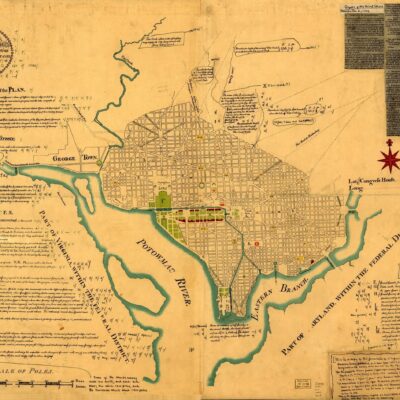

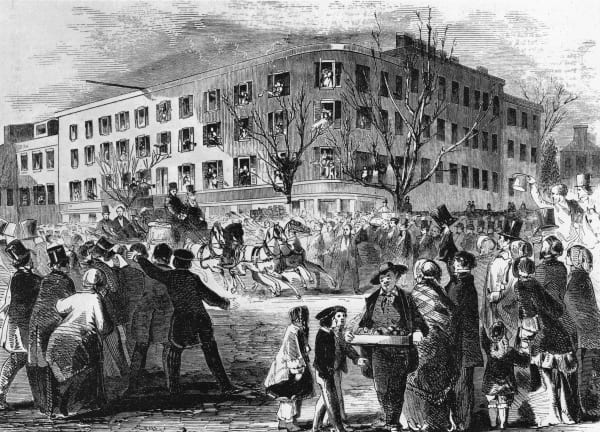

A native Alabaman, Herbert kept up his carousing with his fellow Southrons once he’d arrived in Washington, and it was with vicious hangovers that he and his friend William Gardiner stumbled into the dining room of Willard’s Hotel at 11 a.m. on the morning of May 8, 1856.

The dining room was virtually empty. The Dutch Ambassador, Monsieur Devois sat quietly finishing his breakfast, and waiters Jerry Riordin, Thomas Keating, Jerry Quinn, and his brother Charles were polishing glassware and setting the room for dinner. Herbert growled out an order for breakfast, requesting that Riordin bring him something “damn quick.”

One month as a waiter had already given Riordin the ability to size up a difficult customer, and he brought Herbert what he could, telling the Congressman that as per Willard Hotel rules, breakfast was not served after 10:30 a.m., absent special permission from the temperamental French check, Monsieur Devionese.

Herbert wanted a full breakfast, and he wanted it now. “Clear out you damned Irish son of a bitch,” he told Riordin, who scampered to the kitchen to talk to Devionese and find out if the gentleman from California could be accommodated. Herbert brooked no delay, and ordered Thomas Keating to get him some breakfast.

“I shan’t do it.” Thomas responded, “you already have one boy waiting on you.”

“Go get us some breakfast or go away from here, you damned Irish son of a bitch.” This was more than Keating was willing to stomach. He muttered something under his breath, and now things became truly heated; Herbert stood up and threw his plate at Thomas. Never one to back down from a fight, the 200 pound Irishman responded by throwing a chair in Herbert’s general direction, both of them missed. They charged each other, and grappled in the center of the room.

The waiters stood silently by, watching the fight. Patrick Keating, Thomas’ brother was startled by the sound of breaking crockery, and came charging into the room. He attempted to brain Herbert with a chair, but instead hit his brother. Gardiner joined the fight pulling Patrick off and knocking him down with a blow to the jaw, and then freed Herbert by knocking Thomas in the back of the head with a chair. Thomas stumbled, but kept his balance. With his hands finally free, Herbert drew his derringer with his right hand, and grabbed Thomas’ collar with his left.

Placing the gun against Thomas’ chest, the Honorable Congressman Philemon T. Herbert pulled the trigger. The lead shot went straight through Thomas’ lungs, and embedded itself underneath his shoulder blade. A few minutes later, he was dead, having devoted his last breath to call for a member of the clergy.

He voluntarily turned himself in a few hours later. The United States Attorney for the District of Columbia, Philip Barton Key II, requested $10,000 bail, which two friends of Herbert promptly raised. That evening, Herbert, Key and the two friends had dinner together. Even in that day and age, it was unusually for an attorney to have dinner with the man he would be prosecuting for murder, but Key’s moral scruples were only slightly less strident than Herbert’s. The son of Francis Scott Key, and the nephew of Chief Justice Roger Taney, it was political influence which won Key his position as a United States Attorney. Reputedly the handsomest man in Washington, Key was in the throes of a passionate affair with 18-year-old, Teresa Sickles, the wife of Daniel E. Sickles, Representative from New York State.

Out on bail, Herbert returned to Congress, where Ebenezer Knowlton put forward a motion to censure and expel him. Congress that year had been particularly violent. Representative Granger of New York had engaged in fisticuffs with Representative McMullen of Virginia. Horace Greeley, editor of The New York Tribune had been hit twice over the head with a cane by Representative Rust of Arkansas, but suffered no injuries; the rival New York Herald quipped “Greeley’s head [is] harder than it looks to be.” Most famous of all was the attack on the floor of Congress itself by Preston Brooks on Charles Sumner, which was so severe that it left Sumner crippled. For the expulsion vote, Herbert could count on support from the Know-Nothings, who were anti-Irish, and from Southern Democrats, who wanted Hebert around in case the Presidential election of 1856 devolved upon the House and his vote was needed. The motion was defeated by a majority of nine.

“There is a volume of instruction in that vote,” wrote the Herald, “the men who are in favor of Freedom respect the rights of all, no matter how humble; the men who support Slavery draw a broad line between what are called the upper and lower classes, treading upon those who serve as the would upon dogs.” Southern papers could not have agreed more. The editor of the Montgomery Mail opined “Mr. Herbert…was attacked by a mob of waiters at his hotel in Washington. He promptly put a bullet through the head waiter, and then surrendered to the authorities. There is no doubt he acted in self defense. It is getting time that hotel waiters a little farther north were convinced that they ARE servants, and not gentlemen in disguise. We hope that this affair will teach them prudence.”

Herbert continued to serve in Congress, and after some diplomatic wrangling resulting from the Dutch Ambassador’s refusal to testify, the trial got belatedly got underway in July. Aided by a sympathetic judge and the less than zealous prosecution led by Key, the first jury couldn’t reach a verdict, and was dismissed. “The influences at work to defeat justice during the first trial of Herbert were so strong and palpable,” stated The Ripley Bee, “and the evidence of the partiality of the Judge toward the prisoner was so positive as to rouse a strong feeling of indignation in Washington.” The Judge and Key ignored popular opinion and a second jury, handpicked by Key to ensure an acquittal, found that the homicide was justified.

He returned to California to seek reelection, but while he’d been away a tide of reform had swept the state. The San Francisco Bulletin reported “the homicide was the observed of all observers yesterday as he went about the streets. People looked at him as they would look at a loathsome monster, out of mere curiosity, and not from any respect or desire to make his acquaintance. He was in company with a lot of well known gamblers all day, from whom he probably meets a warm reception.” The gamblers may have been pleased to see him, but not the citizenry. Thousands of Californians signed a petition requesting that he leave the state; which members of the Vigilance Committee presented to him along with a veiled threat that if he didn’t quit the state, he could be expect to be greeted with a hempen cord by a lynch mob.

Herbert fled south to El Paso, and opened a law practice. At the outbreak of the Civil War, he recruited a cavalry brigade, which he grandly named Herbert’s Battalion of Arizona Calvary. Decimated by two years of war, the battalion was broken up, and Herbert found himself elected to the Confederate Congress in 1863. He resigned in 1864, took up his old rank as Lieutenant Colonel and joined the Seventh Texas Calvary. Wounded during the Battle of Sabine Crossroads, he died in June, 1864.