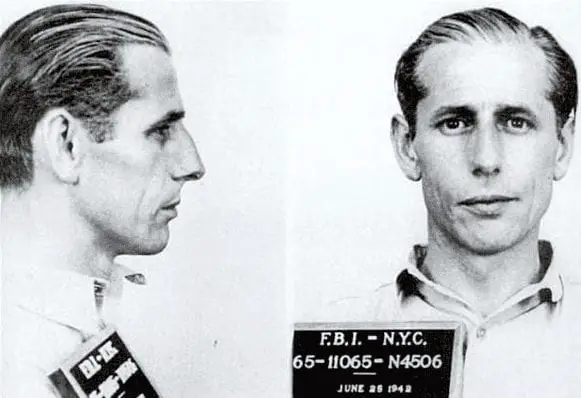

Most of you probably are not aware that Nazi saboteurs landed on our shores early during World War II. On June 12th, 1942, a Nazi submarine reached the coast of Long Island, landing four German spies on the sandy beaches of Amagansett. U.S. Coast Guardsman, John Cullen discovered them while on routine beach patrol. George Dasch, leader of the landing party, bribed Cullen, who promised to keep quiet and left the scene.

As soon as Cullen was out of sight, he sprinted two miles back to the Coast Guard station to alert his superiors. By the time he returned with his Coast Guard colleagues, the Germans were gone. They had made it to the nearest Long Island Railroad station, boarding the next train to Manhattan.

The Nazis had successfully landed a group of spies on United States soil and the largest manhunt in the history of the FBI had begun.

The newsreel below is a classic Hoover and FBI propaganda film, capitalizing on this incident.

Several days later, on June 18th, a second German team of four saboteurs landed near Jacksonville, Florida. They split the team in half, one boarding a train for Chicago and the other for Cincinnati.

Dasch spent several days in New York, under the veil of complete anonymity. It appeared that the two teams were en route to successfully executing their mission of sabotage. Despite this, something rather odd happened to Dasch.

Maybe George was shaken when Cullen came upon them, seeing failure and capture as inevitable. Perhaps he was anti-Nazi with allegiances to the U.S., having lived here from 1922 to the outbreak of the war (he was a naturalized citizen). Whatever it was, George made the decision to expose the plot and turn himself in.

Dasch called the FBI from New York and asked to speak directly with J. Edgar Hoover, stating that he was the leader of the Nazi group that had landed. The agent answering the call was unconvinced that Dasch was who he claimed to be and asked for him to come into FBI headquarters to meet.

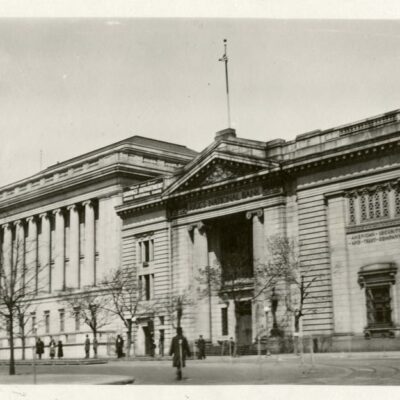

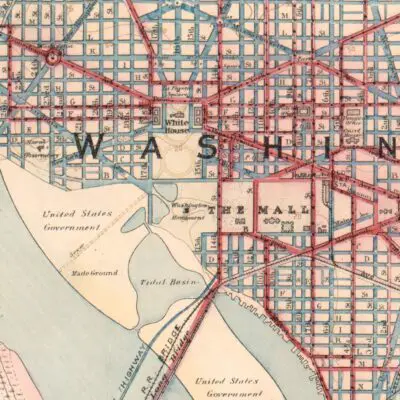

George worked up the courage, convincing himself that he would be welcomed as a hero by Hoover and his team. He boarded a train to Washington, disembarked at Union Station and checked himself into the Mayflower Hotel, room 351.

Again he contacted the FBI and this time agents Duane Traynor and Thomas Donegan met with him in his room on June 18th, the same day the second team landed in Florida. He was now in the hands of the United States Government and within nine days, the seven remaining saboteurs were captured.

Hoover wrote a boastful letter to President Roosevelt lauding the actions and vigilance of his bureau, actions which prevented Nazi attacks on American soil. J. Edgar gave FDR the impression that it was the FBI’s actions alone that brought the men in, failing to mention that without Dasch’s surrender, eight Nazi spies would still be wandering about freely.

Roosevelt wanted a swift trial under a thick veil of secrecy and called for a military tribunal of seven generals to be held within the Department of Justice building.

All eight would-be saboteurs pleaded innocent, denouncing any allegiance to Hitler or the Third Reich. The prosecution, headed by Attorney General Francis Biddle, asked for the death penalty. On July 27th, the defense rested its case and it was handed over to the seven generals for decision.

The generals prepared their report and sent it — with the 3,000-page trial transcript — to President Roosevelt in the Oval Office. The voluminous report and papers were exceedingly time-consuming for the President and the country waited for over a week to hear Roosevelt’s final decision. On August 7th, the Washington Post published an article about the delay.

Washington, Aug. 7–A flood of rumors to the effect that President Roosevelt had made a decision in the case of the accused Nazi saboteurs and that six of them were to be executed immediately was answered today at the White House by a short and unadorned denial.

It was announced that the President had not finished reading the voluminous report and recommendations of the military tribunal that tried the men and was uncertain when he would finish it.

Tonight the eight accused men were being held in the District of Columbia jail where they have been since the start of their trial. They were under a heavy armed guard.

…

The rumors that filled the Capital, as well as many other cities, varied considerably. At first it was announced positively that six of the Nazi spies were to be executed immediately; that the President already had given the orders. Later the rumors were amended to read that the saboteurs had been given a reprieve.

Aside from the White House denial there was, meanwhile, no indication at the city jail that any sudden execution was in contemplation. The death chamber was dark. The accused still were in their widely separated cells on the south floor of the second wing.

In each cell sits an unarmed soldier to prevent attempts at suicide while armed soldiers patrol the corridors. No visitors are allowed.

The following day Roosevelt had made his decision and taken the recommendation of the seven generals. On August 8th, 1944, six of the Germans were executed and two others were given hard-labor sentences. For his role in bringing all the conspirators in, Dasch was given the lightest sentence of 30 years.

Washington. Aug. 8–Six Nazi saboteurs paid with their lives today for their thwarted plans and preparations to destroy key war facilities in the United States.

They were electrocuted in the District of Columbia Jail on the Presidentially approved recommendation of the seven-member military commission which concluded trial in Washington last Monday.

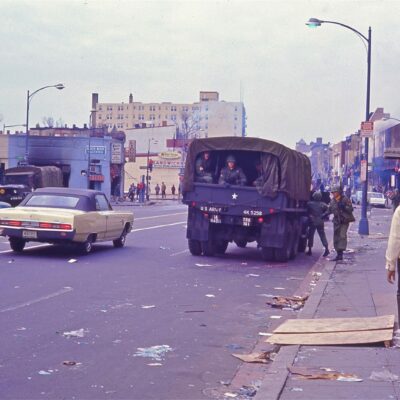

Outside the gate of the jail a crowd gathered, dissolved and gathered again. As the ambulances carrying the bodies were driven away a heavily-armed squad of soldiers kept order in the streets. They were armed with sawed-off shotguns, submachine guns and rifles.

…

The men executed were:

HERBERT HANS HAUPT.

HEINRICH HARM HEINCK.

EDWARD JOHN KERLING.

HERMAN OTTO NEUBAUER.

RICHARD QUIRIN.

WERNER THIEL.

Upon confirmation of all six executions, the White House issued a brief statement which concluded with the statement, “The records in all eight cases will be sealed until the end of the war.” The President was not in Washington. He was relaxing at Shangri La — the Maryland retreat now known as Camp David.

The dead were quickly loaded into two ambulances and driven at full speed to Walter Reed Army Hospital for autopsies. Several days later, each body was placed in individual pine boxes and taken to Blue Plains Potter’s Field in Anacostia for burial in unmarked graves. Blue Plains used to be the site of the Home for the Aged and Infirm and now it’s the site of a D.C. Water and Sewer Authority treatment plant. What’s crazy (or cool) is that you can request a tour of the Blue Plains facility, which is at 5000 Overlook Ave. SW. I’m guessing not one reader has been there yet or even knew you could do that.

Below is a silent reel which has the ambulances departing the jail (near the end).

The two Germans not executed were deported in 1948 by President Truman.

If you found this story fascinating, follow us on Twitter or Facebook to get daily updates from our blog.