John W. Lewis’ Vision for Uplifting the Black Community

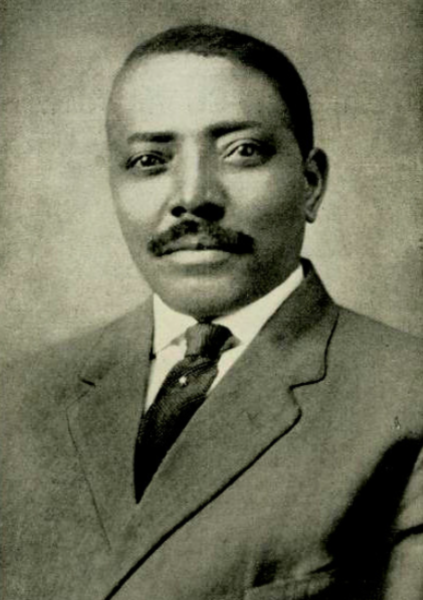

As The Washington Post highlighted in February 2020, the Whitelaw Hotel was the brainchild of John Whitelaw Lewis, the son of a former slave. Lewis started out as a construction laborer, hauling bricks around Washington D.C. job sites. Through determination and self-education, he rose to become president of the local laborers union.

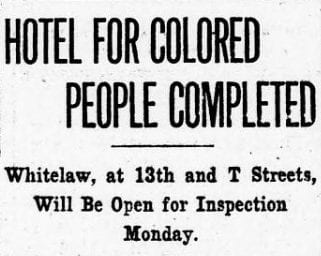

As The Washington Post described, Lewis urged fellow African Americans to focus on “education, cooperation and shared responsibility” to uplift the race. In 1913, he founded the Industrial Savings Bank, the first black-owned bank in the city, to help members buy homes. Then in 1919, amidst heightened racial segregation and tension in America under Woodrow Wilson’s presidency, Lewis commissioned the luxurious Whitelaw Hotel.

He invested $150,000 to construct an elegant lodging for upper-class black travelers denied access to white-owned hotels. The Washington Post reported that when the Whitelaw opened, Lewis emphasized the hotel as a ray of hope, saying “we must be in a position to take care of the people of our race.” His ambitious project aimed to uplift the community as a source of pride despite oppression.

Isaiah T. Hatton’s Stunning Architectural Design for the Whitelaw Hotel

To design the opulent Whitelaw Hotel, John W. Lewis selected prominent local black architect Isaiah T. Hatton. As The Washington Post highlighted, Hatton was one of the nation’s first registered African American architects.

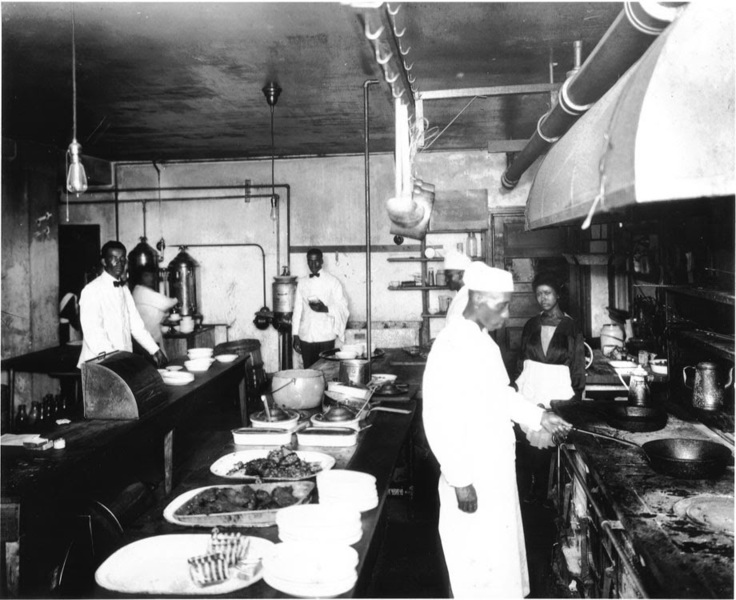

Hatton designed the hotel in a classical Italianate architectural style, featuring a grand stained-glass skylight and elegant plasterwork, tile, filigree, and interior details. As described in The Washington Post, Hatton’s vision complemented the artistry of the black craftsmen who expertly constructed the hotel—pouring concrete, laying brick, installing elevators, plastering walls, and more.

When the Whitelaw opened in 1919, an estimated 20,000 people came just to admire Hatton’s crowning achievement. The Washington Post noted “there was a feeling of uplift” from his elegant design that showcased the skills of the black builders. Hatton created a luxurious space where black patrons could relish amenities and dignified treatment too often denied at white-owned establishments.

In its early decades, the Whitelaw hosted leading black figures including Langston Hughes, Duke Ellington, George Washington Carver, Jesse Owens, and activist Mary Church Terrell, according to The Washington Post in October 1992. The hotel became a hub for upper and middle-class black travelers during segregation. Despite oppression, it stood as a proud emblem of black excellence in the nation’s capital.

The Hotel’s Fall Into Decline and Near Demolition

After integration began dismantling enforced segregation in the mid-20th century, the once-thriving Whitelaw fell into decline as black patrons turned to newly accessible white-owned hotels. As The Washington Post described in July 1977, “with the advent of integration during the 1940s and ’50s, black people began patronizing white-owned hotels, and the Whitelaw, once home and performance venue for some of the most famous black entertainers — including Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway and Ella Fitzgerald — lost its sheen.”

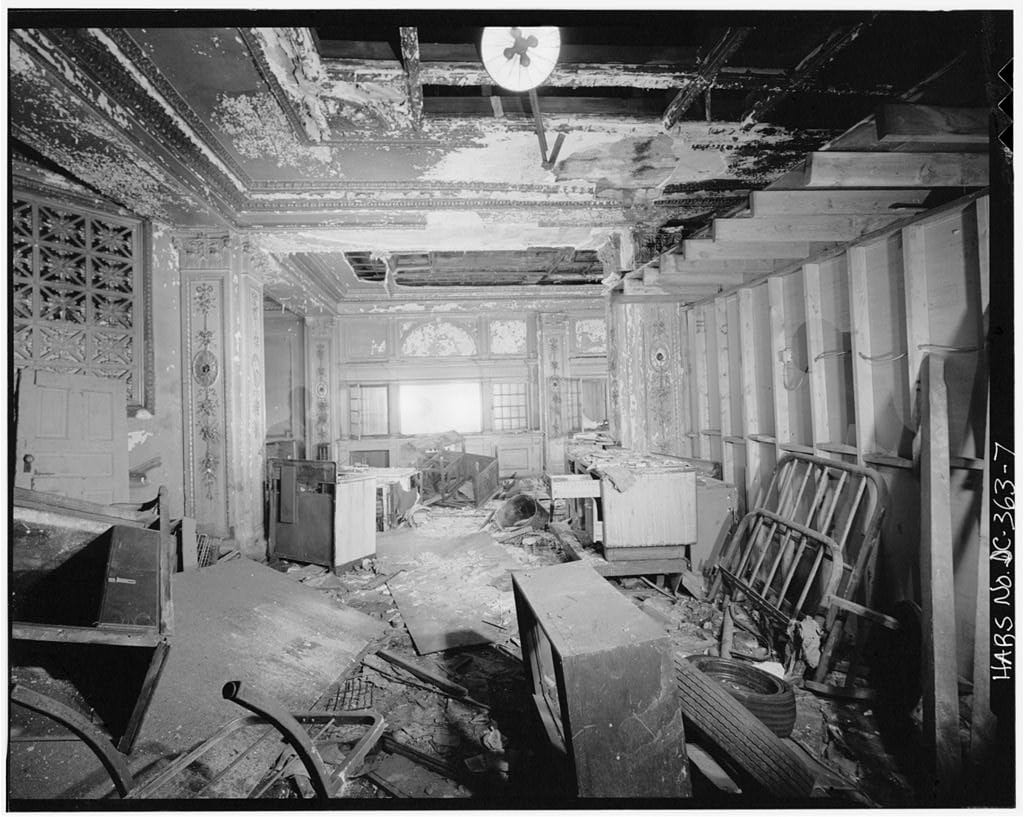

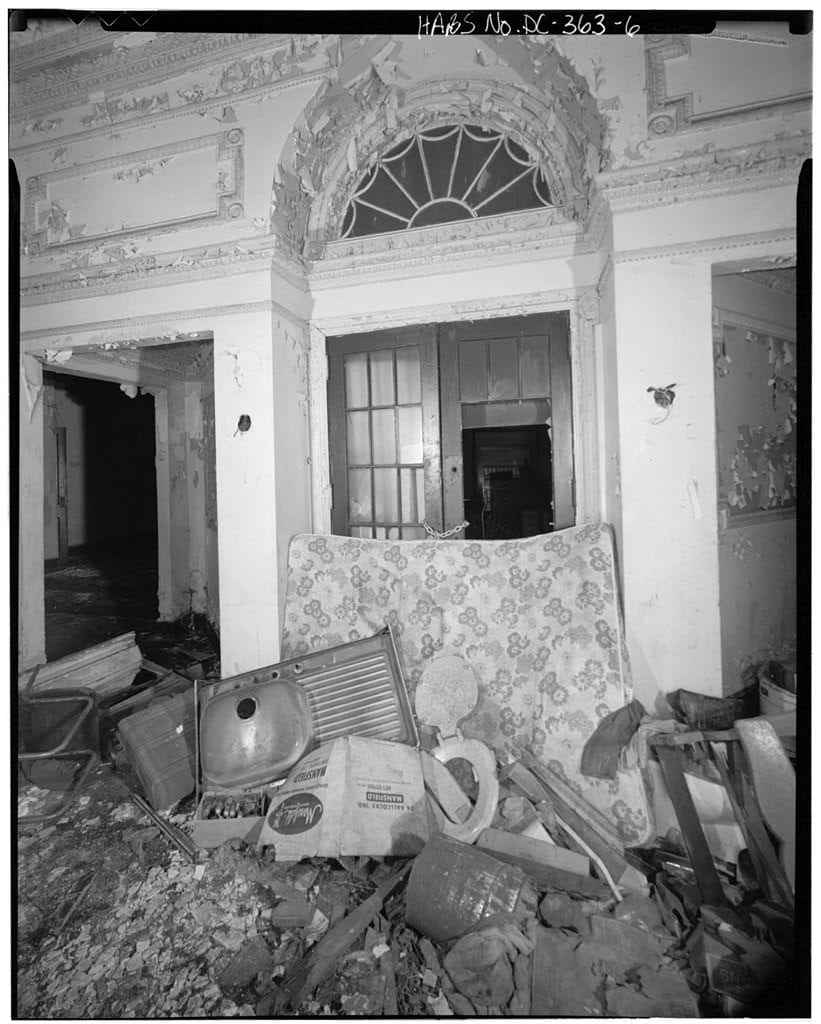

The Whitelaw became “a flophouse, a dope den and the scene of multiple homicides,” according to The Washington Post. Closed by the city in 1977 for code violations, it sat vacant for years as the “hotel’s historic significance was buried under a mountain of code violations.” A devastating fire in the 1980s burned through the roof.

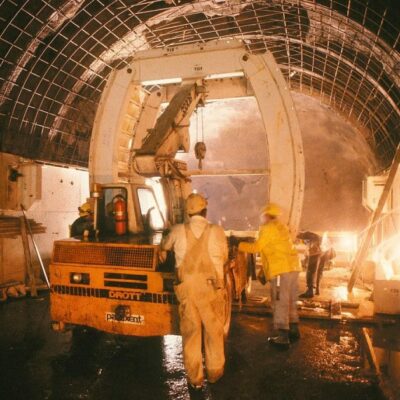

The Washington Post noted it was “extraordinarily sturdy structure” crafted by skilled black builders that kept the Whitelaw from complete ruin. In the 1990s, nonprofit Manna Inc. purchased the burnt out shell and meticulously renovated it into low-income housing, restoring the Whitelaw’s splendor.

The Whitelaw Hotel is Reborn As a Living Landmark

While no longer operating as a hotel, the revived Whitelaw remains a living landmark exemplifying the ambitious vision of John W. Lewis and artistry of Isaiah T. Hatton. As The Washington Post noted, their work created “a feeling of uplift” and pride for the black community despite the oppression of segregation.

Nearly demolished, the painstakingly restored Whitelaw endures as a monument to the outstanding achievements of Black Washingtonians throughout the city’s complex history. The hotel’s rebirth parallels the progress of African Americans in D.C., overcoming decades of discrimination to secure greater access and opportunity.

Though the segregated era it represented has passed, the Whitelaw’s elegance conjures the vibrancy of early 20th century Black Broadway. Lewis and Hatton’s towering accomplishment stands as a reminder of Black excellence thriving even in times of injustice. The Whitelaw persists as a symbol of both the inequities of the past and the triumphs of the determined African American community that shaped Washington D.C.