Early Planning Raises Concerns

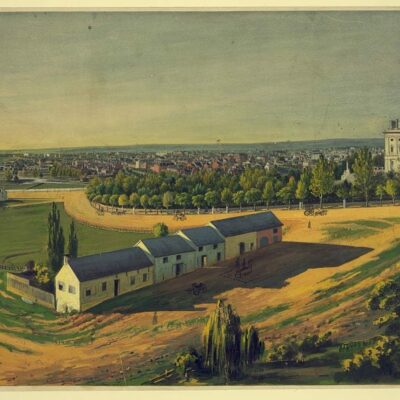

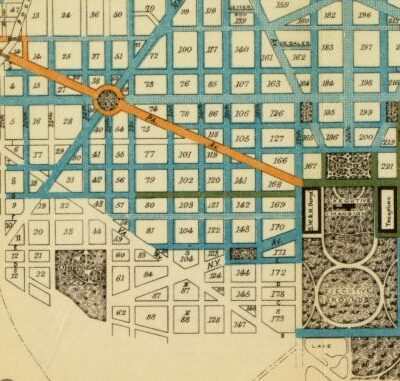

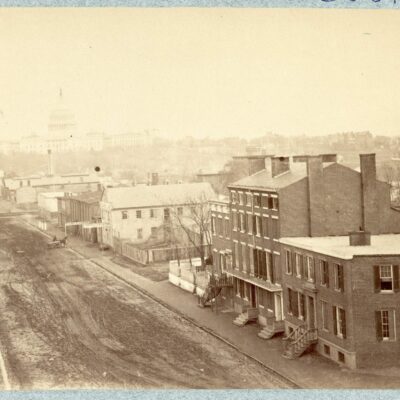

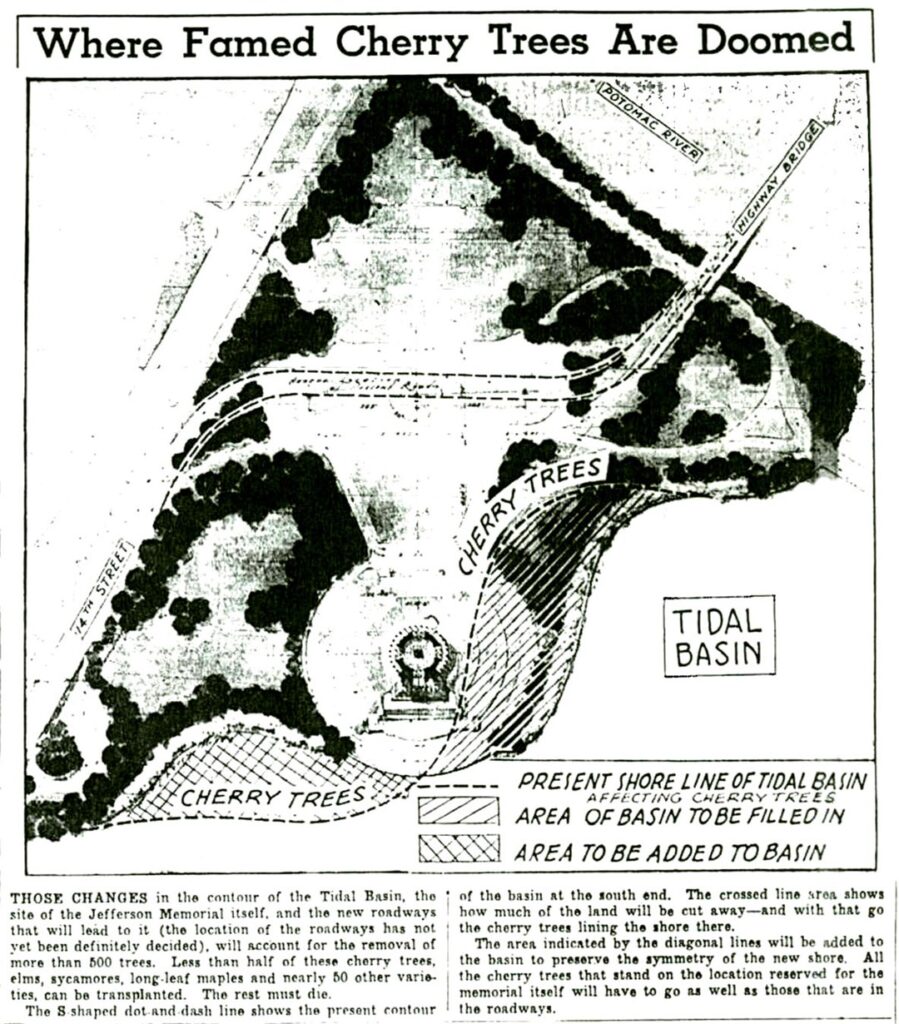

In 1912, the mayor of Tokyo gifted 3,000 cherry trees to Washington D.C. to enhance the landscaping of the Tidal Basin. By 1938, the blossoming Japanese cherry trees lining the basin had become iconic, attracting thousands of tourists every spring to enjoy the scenic natural beauty. That same year, proposals for a memorial to Thomas Jefferson threatened the beloved trees and serene landscape, igniting heated controversy.

The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Commission (TJMC), authorized in 1934 and chaired by New York Congressman John J. Boylan, unveiled proposals in 1938 for an imposing memorial structure resembling the Roman Pantheon. This bold neoclassical vision required eliminating a significant number of cherry trees around the Tidal Basin to clear space for construction.

Immediate backlash emerged as details were publicized. A Washington Post editorial called the extravagant project “flim-flam” and an incongruous tribute to Jefferson’s democratic spirit and love of nature. Washingtonian C.L. Woosley, a local resident who wrote a critical letter published in the Post, suggested alternatives like a Jefferson planetarium, arguing the ostentatious memorial design shouting “look at me!” hardly honored Jefferson’s humbler principles. Woosley felt a planetarium would better reflect Jefferson’s curiosity and forward-thinking spirit. The American Federation of Arts agreed with Woosley’s perspective, claiming in a statement that the memorial “does not express Jefferson’s ideals, philosophy, or manner of living.”

At the April 1937 House hearings over the proposal, the Women’s Club Federation lamented the planned “pile of brick, stone and mortar” was a poor use of funds compared to more useful monuments like schools or hospitals that would better reflect Jefferson’s “care for the welfare of all people.” Opponents like Woosley and Washington artist Royal H. Carlock argued the design was out of step with contemporary times, with Carlock asking “Why destroy the beauty and grandeur that enshroud Lincoln” with an imposing classical façade incongruous with Jefferson’s forward-thinking spirit?

Despite the swell of objections, Congressman Boylan and the TJMC stood firm in their conviction that only a bold neoclassical vision on the scenic Tidal Basin location could appropriately honor Jefferson on par with memorials for fellow revered presidents Washington and Lincoln.

Cissy Patterson’s Crusade Against FDR

As controversy brewed over the memorial plans in late 1938, one leading figure in the opposition movement was the larger-than-life newspaper publisher Eleanor “Cissy” Patterson. Patterson owned The Washington Herald and Times-Herald, platforms she increasingly used to voice criticism of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s policies.

Driven by escalating personal rivalry with FDR, Patterson seized on the memorial tree removal issue to galvanize her women readers against demolishing the cherished basin cherry trees, which she portrayed as an egregious government overreach. Through rallies at her lavish Dupont Circle mansion and fiery editorials denouncing FDR’s “lies” about the threatened trees, the audacious Patterson brought national visibility to efforts to thwart Roosevelt’s beloved memorial project. Her active crusade against the president fueled much of the fervent public pressure around saving the cherry trees.

Cherry Tree Rebellion and 150 Outraged Protestors

Despite the swelling opposition, Congressman Boylan and the TJMC stood firmly by their conviction that only a bold, imposing neoclassical memorial on the scenic Tidal Basin location could appropriately honor Jefferson on par with the monuments to Lincoln and Washington.

During heated April 1937 Congressional hearings over the proposal, Chairman Boylan dismissed utilitarian alternative visions like a Jefferson library or auditorium as improperly honoring Jefferson “alongside Washington and Lincoln.” Boylan insisted a stately classical façade was the sole worthy tribute.

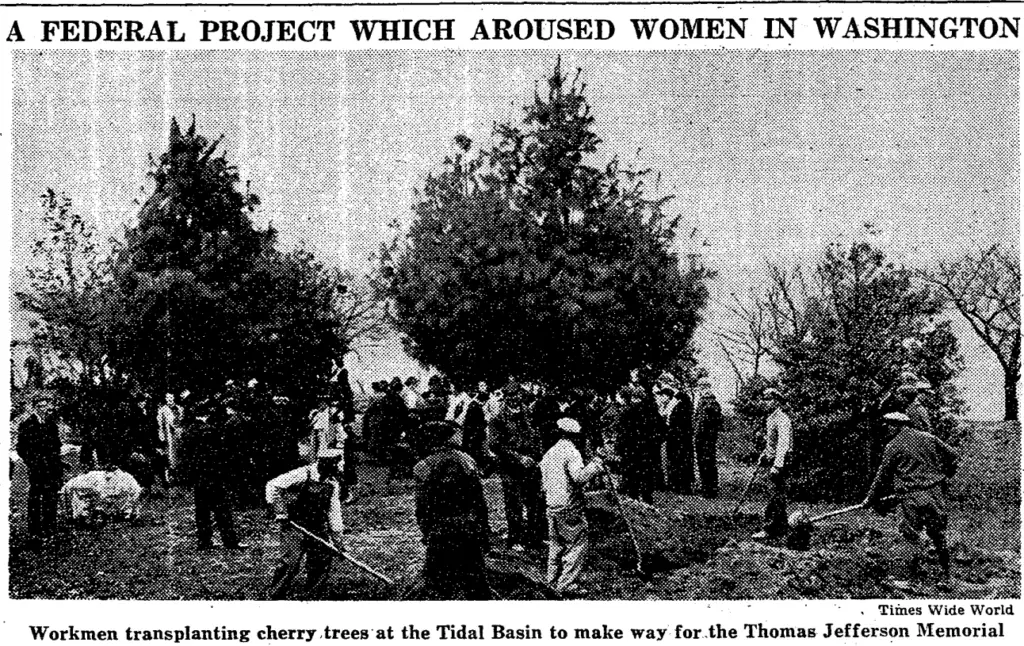

Public tensions climaxed in November 1938 as the National Park Service posted notices and prepared to begin the controversial process of permanently dislodging cherry trees to commence construction. On November 17th, around 150 outraged protestors, including many from local women’s clubs, took dramatic direct action by chaining themselves to doomed cherry trees marked for imminent removal.

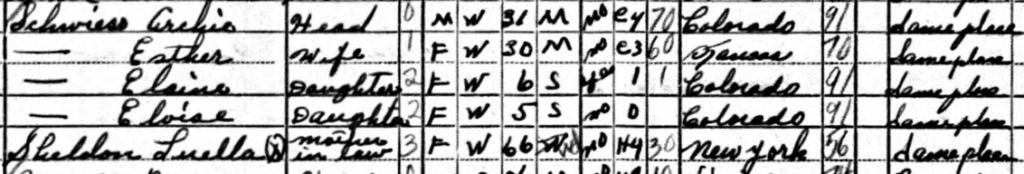

Luella Pine Sheldon, an Arlington woman, encapsulated the protestors’ passion in a poem titled “Do Not Let Them Go!” published in the Washington Post, lamenting “Would not browned leaves and petals white, Scattered by winds in wanton flight, Sadly grieve him if he knew?”

Quickly dubbed the “Cherry Tree Rebellion” by newspapers, the women’s actions drew significant national attention. Angry demonstrators scuffled with workmen attempting tree removal, decrying the perceived “vandalism” of destroying the beloved and iconic cherry trees.

President Franklin Roosevelt publicly dismissed the escalating uproar as overblown “flim-flam,” refusing to directly address protestors’ concerns. But facing growing pressure, he reluctantly halted imminently planned tree removal until Congress reconvened, effectively forcing a pause for reconsideration of balancing Jefferson’s legacy with preserving the scenic basin’s natural beauty.

The dramatic Rebellion stirred vigorous public debate over whether uprooting the Japanese cherry trees betrayed the spirit of Jefferson’s teachings more than honoring them. For opponents, saving the trees protected local interests over federal power. But Boylan refused to abandon plans he felt properly honored Jefferson’s national stature.

Ongoing Opposition and Construction

In the months after the dramatic Cherry Tree Rebellion, persistent opponents continued publicly urging Congressman Boylan and the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Commission to abandon or modify their rigid neoclassical plans. Protesters pushed for incorporating a more populist, nature-inspired vision they felt better resonated with Jefferson’s intimate ties to the land and love of trees.

But Boylan and the Commission proceeded undeterred, arguing no architectural style beyond imposing, columned neoclassical aesthetics could properly honor Jefferson and symbolize his prestige alongside fellow revered presidents Washington and Lincoln.

Boylan maintained that soaring domes, dramatic facades, and Ionic columns represented Jefferson’s rightful venerated place in the American political pantheon. After Nazi Germany’s September 1939 invasion of Poland abruptly shifted America’s focus overseas, visible public opposition to the Memorial Commission’s plans rapidly quieted as international crises took center stage.

With the benefit of distraction diluting public scrutiny, preliminary construction for the memorial finally quietly commenced in late 1939. Builders broke ground on a slightly scaled back yet still bold and neoclassical vision for the sprawling Jefferson Memorial.

The completed stately Rotunda design firmly enshrined the Commission’s conception of Jefferson as a venerated Founding Father figure over the more complex populist leader Cherry Tree Rebellion protesters had passionately invoked. While Boylan saw the dramatic dome as representing Jefferson’s place among America’s most revered early statesmen, opponents viewed the costly imposing edifice as incongruous with the people’s president.

The constructed memorial ultimately embodied the federal Commission’s authority to define history on public land over local stakeholders’ dissenting vision. Yet the earlier rebellion had forced greater public reflection on how to properly balance commemorating Jefferson’s nuanced democratic legacy moving forward.