The Dawn of Washington’s Glassmaking Excellence

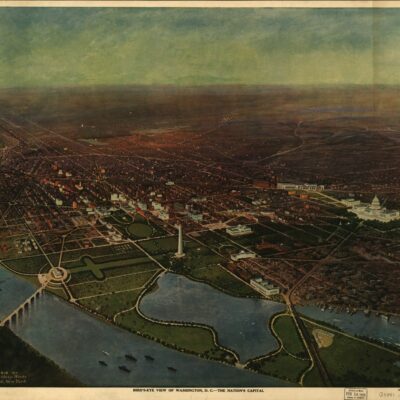

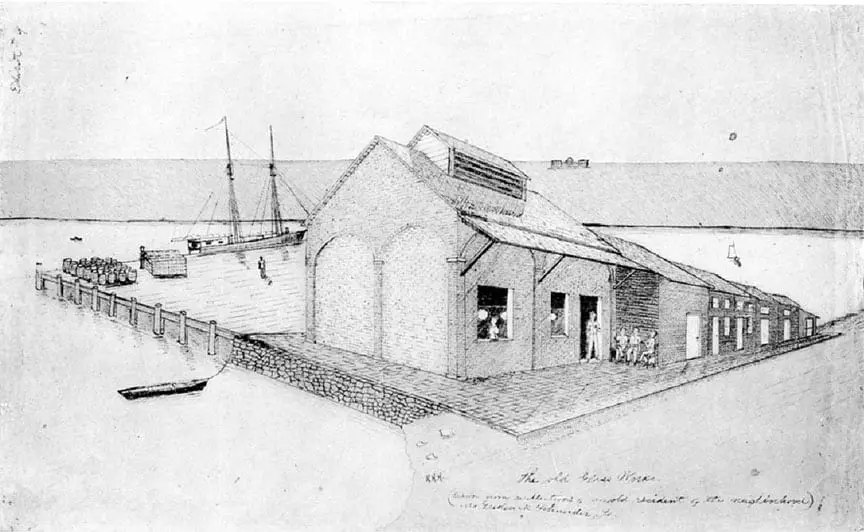

In 1807, the Old Glass House was established by brothers Andrew and George Way, marking a significant milestone in early American industrial history. Positioned strategically at the western edge of what is now the National Mall, near the Lincoln Memorial, its location by the Potomac River was pivotal for the inflow of raw materials and the distribution of its primary product, window glass. At the outset, the factory boasted ten furnaces and employed approximately 100 workers, including skilled Bohemian glassblowers. This blend of mechanization and craftsmanship ensured a steady production output.

The factory’s architecture and operational flow were paragons of efficiency. From the furnaces to the blowing room and onto the flattening house, each step in the process was streamlined to transform raw materials into market-ready glass. Artisans in the cutting room meticulously scored and sized panes, while supplementary structures like the molding and mixing rooms facilitated the preparation of materials. This tightly controlled process maintained the secrecy of proprietary techniques and the integrity of a highly skilled workforce.

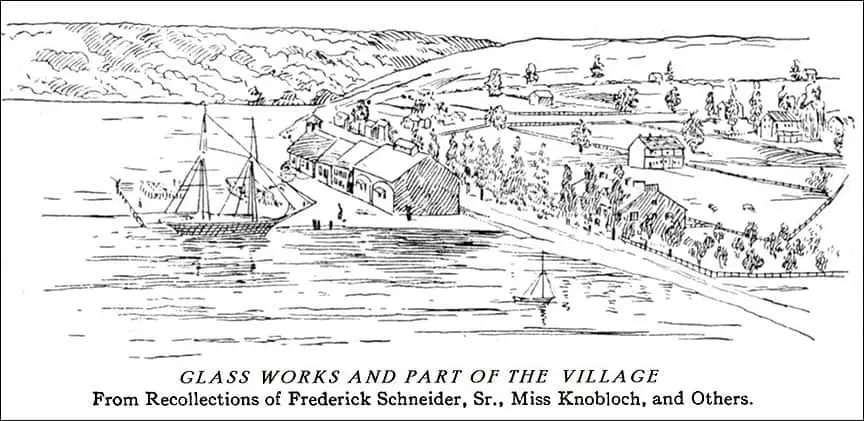

Under the Way brothers’ stewardship, the Old Glass House’s reputation for quality window glass quickly spread, reaching markets as far as Ohio and Illinois and rivaling the prestigious Boston crown glass. This golden era not only underscored the company as a formidable player in the national glass market but also fostered the growth of a self-sustaining village, complete with housing, a company store, and a wharf.

Community Life and Legacy at the Old Glass House

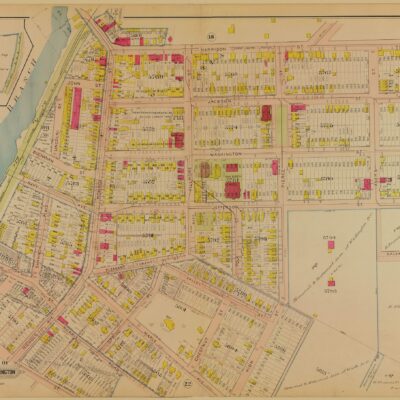

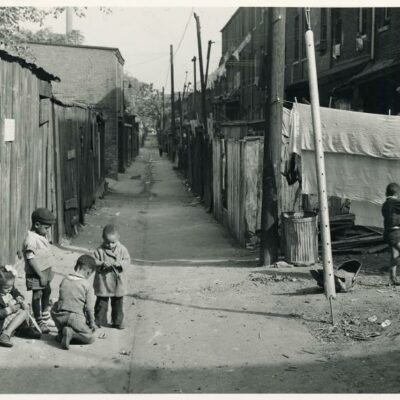

Beyond its industrial achievements, the village surrounding the Old Glass House evolved into a vibrant community where workers and their families flourished. At the heart of this community were “Glass-House Row” and “Glass Blowers Row,” providing housing for many of the factory’s workers in broad two-storied-and-attic brick dwellings. Characterized by rows of fine Lombardy poplar trees along Water Street and other lush greenery, the area offered a picturesque living environment. Moreover, residents took pride in their homes, embellishing them with porches, verandas, and gardens brimming with vines, flowers, and trees. This cultivation of both private and public spaces mirrored the workers’ comfort and contentment with their living conditions.

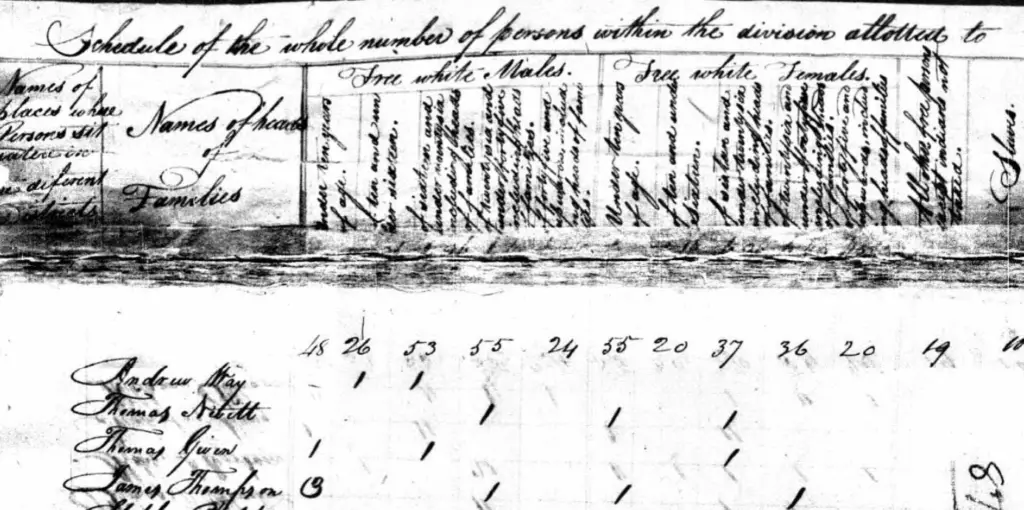

Furthermore, the community was marked by its diversity, encompassing both free individuals and families that owned slaves, yet it maintained a close-knit bond with strong attachments among its members. Illustrated by anecdotes of bravery—such as a young girl saving a slave girl from drowning—and tales of communal support during the cholera epidemic of 1832, the depth of community spirit that permeated the settlement was evident. Additionally, this spirit was showcased through the residents’ leisure activities, including fishing, boating, and picnics across the river at Custis’s Spring, highlighting a community that not only worked together but also celebrated and tackled life’s challenges as one.

Ultimately, the Old Glass House’s success during its peak years in the early 19th century is not only a testament to a legacy of innovation and craftsmanship in American manufacturing but also to the creation of a dynamic community that made significant contributions to the social and urban fabric of early Washington D.C.

A Tumultuous Era: Decline and Transformation

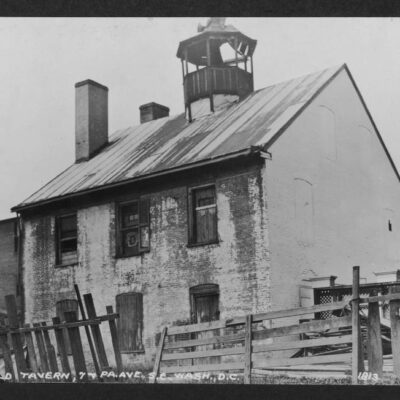

Following the insolvency declaration in 1829, the Old Glass House experienced a series of ownership changes, each failing to restore its early success. The Bank of the United States’ attempt to rejuvenate the factory was short-lived, and subsequent efforts by Cornelius McLean Sr., and then by partners Lewis Johnson and Truman Cross between 1835 and 1838, did not yield sustainable results. By the late 1830s, the factory had endured a prolonged period of decline.

Commander John Rodgers acquired the factory in the late 1830s, marking the beginning of its final chapter. However, Rodgers did not engage in glass production directly. Ownership changed hands again in the early 1850s when Charles L. Coltman took over, definitively shifting the site’s focus away from its original glassmaking purpose. Under Coltman, the premises were leased to industrial firms, further distancing the property from its glass production heritage.

By the mid-19th century, the Old Glass House’s structures had deteriorated significantly, leading to various repurposings of the site. The area experienced a brief resurgence during the Civil War, but soon after, the development of Potomac Park erased any remaining traces of the once-flourishing glass works.

Despite the physical disappearance of the Old Glass House, its legacy endures through historical records and narratives, serving as a testament to Washington D.C.’s industrial evolution and the pioneering spirit of its founders. The stories of the factory and the communities it supported, such as the early village of Hamburg/Funkstown, remain vital chapters in the capital’s history, illustrating the lasting impact of industry on community development and the urban landscape.

The transition of the site into a forgotten piece of history is underscored by a local resident’s 1892 recollection of the area during the Civil War, noting its stark contrast to the bustling activity of its past. By the late 1890s, no evidence of the industry that once spanned over two acres remained, with the establishment of Potomac Park marking the end of the glass house’s over 80-year legacy.

Today, few visitors to the Lincoln Memorial area are aware of its historical significance as the site of Washington D.C.’s first glassmaking complex, highlighting the importance of archaeological efforts and historical research in uncovering and preserving such legacies.