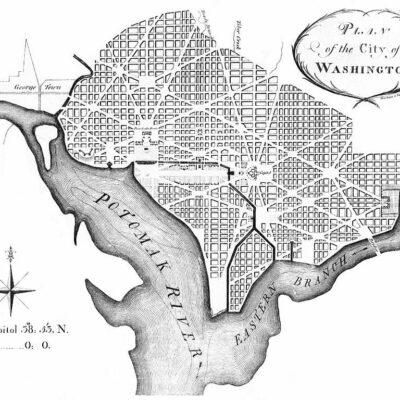

Pre-dating Uber drivers by about 160 years, the hackmen of Washington used to provide transportation to locals and visitors alike. Hackmen used to rule the streets of the city, taking people wherever they wanted to go. (A hackman was one who drove a hackney around the city —

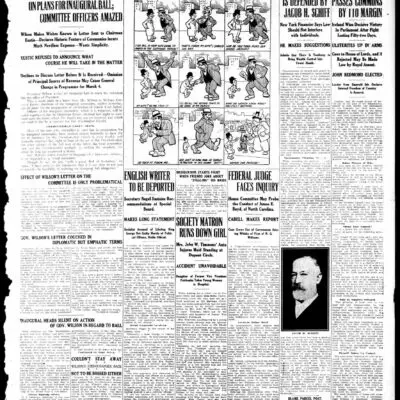

We came across a fascinating old article in The Washington Post, printed on April 6th, 1890, detailing the old stories of hack drivers in the city.

An interesting chapter of local history might be written about the hackmen … Time was when a Washington hackman didn’t have to work more than a dozen days a month to reap an excellent income.

…

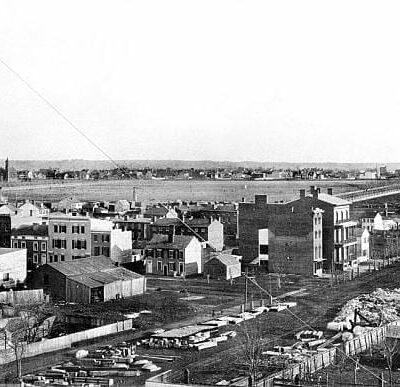

In those days the Metropolitan Hotel was practically the center of the city. Here it was the hackmen gathered and wanted for their patrons. Every morning the policeman whose duty it was to keep the hackmen within reasonable bounds would take a big piece of chalk and mark a line all along the old flagstone sidewalk, two feet from the edge of the curbstone. Then when the hackmen came they backed their traps up against the curb in a long line, and stood along the sidewalk outside the chalk-line and waited for fares. They were not allowed to go beyond the chalk-mark, and the officer stayed there to see that they didn’t. When any one that looked as if he had money enough to ride in a hack came out of the hotel or down the street the hackmen would all strike an attitude of intense solicitude, and, jerking up their right hands with their whips in them, would say, “Ride sir?” or “Hack?”

…

Some few old Washingtonians may remember the first hackman in Washington. He was a smartly-dressed young Englishman, named Goddard, who came here the early part of the century. He had a little money, and he invested it in what was in those days considered an excellent turnout, though it would not excite any very enthusiastic admiration now. It was a coach with its massive box hung on leather springs above four stout little wheels, and the two horses; harness was lavishly ornamented with brass. This original hackman did a most thriving business.

It’s fascinating to think of the city back during these days, and as your can imagine, the hackmen of yesterday weren’t that different from the cabbies of today, though seemingly a little more aggressive in pursuing their business. The story continues.

Washington was then as now full of well-to-do strangers, who were used to having carriages at their disposal at home and they took most kindly to the Englishman’s innovation/ So well did the Englishman do that after about ten years’ of prosperous hacking he retied a rich man, as those times went. … In those days there were no police regulations governing the rates for hackmen, and they charged whatever they could get. But competition lowered the rates, and finally the local authorities stepped in and fixed the rates by law, the Englishman tired of working so much harder for so much less money, and after disposing of his trap he went back to England to live the rest of his life like a gentleman, as he expressed it. But he gambled, and drank, and married, and before ten years he was back here again driving a hack. He died a hackman some time in the sixties.

The article continues to talk about the growth of the business and the need for regulation and licensing, but where it gets interesting is the focus on the Bladensburg dueling grounds.

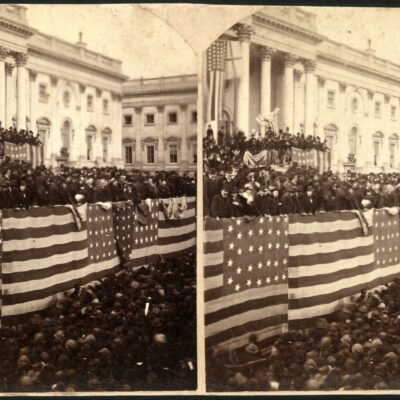

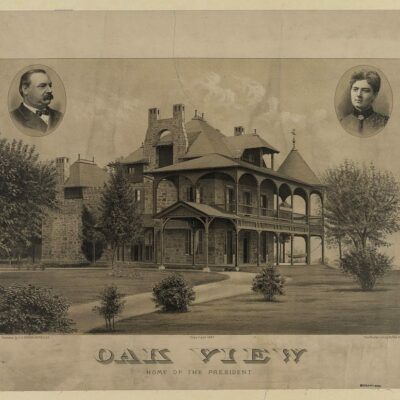

In the old days the hackmen used to regard the then all too frequent duels as Godsends to their business just as now-a-days the cabbies hail prize fights with delight, as furnishing an abundance of business, and that, too, at their own prices. The regular tariff for taking a dueling party out to Bladensburg was $20. One old gentleman with white whiskers who made money enough out of the hack business years ago to start him a more lucrative business told a POST reporter the other night how he took General Prior out to Bladensburg for his duel with the Virginia Congressman. He was told by Prior’s physician to be at the north front of the Capitol (it was not the same Capitol then it is now) at 7 o’clock in the morning.

…

The duel took place on the Maryland side of the line. I think their friends placed them so far apart that there wasn’t much danger of either of them being hurt on purpose. Anaway [sic] after two or three shots being fired someone shouted that the police were coming, and everybody ran for their carriages, and we came back to town.

If you’re not familiar with the Bladensburg dueling grounds, the Wikipedia article has some interesting background on it. It’s where Francis Scott Key’s son Daniel was killed in a duel, and naval hero Stephan Decatur (i.e., the Decatur House on Lafayette Square) was mortally wounded. The story continues.

“I have hauled most of the prominent men of the times before the war at one time or another. Daniel Webster used to ride with me often. He was the most generous men I ever knew, I guess. Lots of times he has stopped me on the street to give a poor woman money. Often he would empty his pocket into a woman’s hand without ever counting the money at all.”

“Calhoun used to ride with me sometimes, too. He was always talking to himself. He would be mumbling away to himself when he got in, and he would keep right on till he got to where he was going, and thne the driver would have to tell him before he would notice it.”

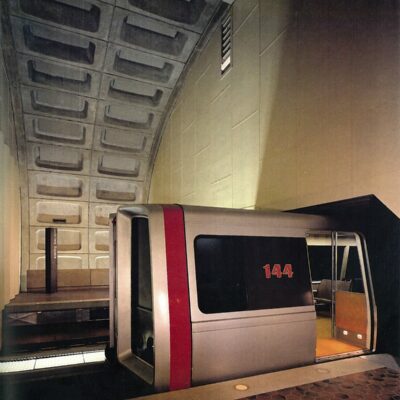

As you can imagine, the hackman’s livelihood was threatened and came to an end in the latter part of the 19th century with the building of streetcars throughout the city (which would also be killed off by the automobile and bus).

Old Charley Burch and “Marsh” Mullen are two more of the old-timers. They were both driving hacks here during the war. It was the building of the streetcar line that ruined the hackman’s business. People–Washington people–don’t ride in hacks at seventy-five cents an hour when they can ride in the street cars for five cents.