This is a guest post by Aaron.

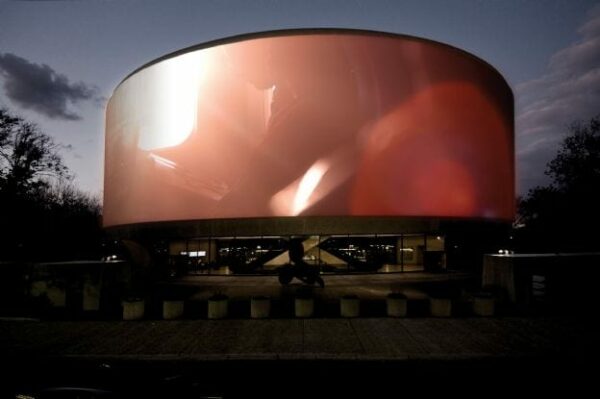

Art fans will focus Thursday night on the outer walls of the Hirshhorn Museum. Eleven video projectors will paint the Smithsonian’s modern and contemporary ring with 360 degrees of a looping film called, “SONG 1.” The Hirshhorn’s exterior will become exhibition space as artist Doug Aitken transforms the circumference into an inside-out movie screen. Just for a few weeks.

It all sounds very cool. But this is a blog about the past. And there are some fascinating stories about the Hirshhorn’s prime spot on the Mall. The New York Times used their editorial page for a scathing architecture review in 1974. And did you know that an entirely different museum stood at the same location until 1968?

Before they invented the wheel

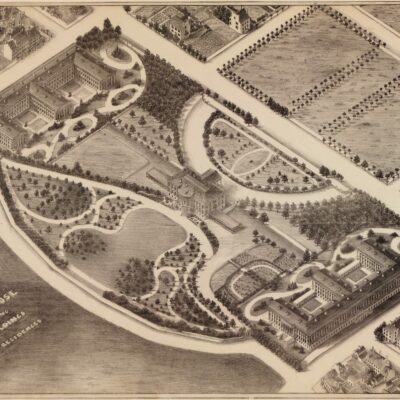

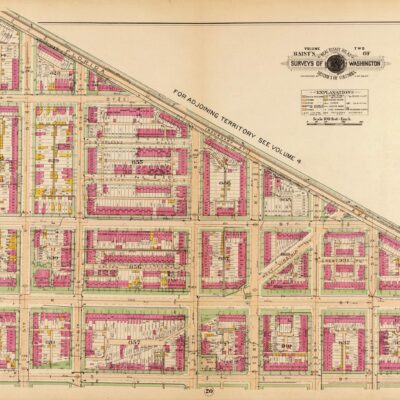

The Army Medical Museum changed names a few times, sitting at the corner of Independence Avenue and 6th Street, SW from 1887 through the end of the 1960s. Collections shifted between the military and the Smithsonian. The massive space, called “Old Red Brick,” housed medical offices, labs, and a library. Branded as the National Museum of Health and Medicine in its final decade, the building welcomed as many as 1 million visitors a year.

“Old Red Brick” was designated as a national historic landmark in 1964 – but that didn’t prevent its demolition. Landmarks aren’t forever. And officials soon declared that the historic label applied to the nation’s medical artifacts – not the building. Deals were already underway for a new Mall museum housing a massive art collection.

From medical relics to modern art

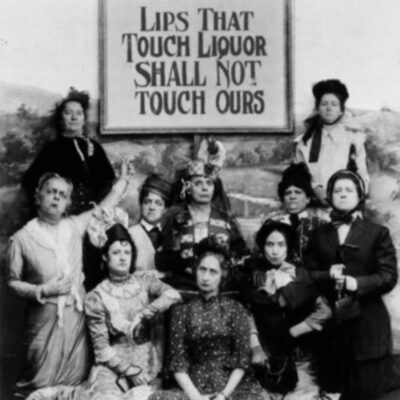

Congressional testimony from 1966 notes that a handful of elected representatives opposed razing the medical building. But they didn’t stand a chance. President Johnson and his wife helped cajole one of America’s most prolific art collectors to give a gift to the nation. The medical library moved to Bethesda. Artifacts (including a leg amputated during the Civil War) eventually moved to Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Congress appropriated $15 million for construction of an art museum on the Mall and the collector, Joseph H. Hirshhorn, added $1 million to help fund the building project. His artistic contributions were valued at $100 million in 1974 (more than $460 million in today’s money – not even accounting for an increase in the art’s value). Hirshhorn earned his fortune in uranium mining.

Here’s a short newsreel of LBJ introducing Hirshhorn’s gift. You’ll notice some familiar sculpture in its pre-D.C. home, a Connecticut estate.

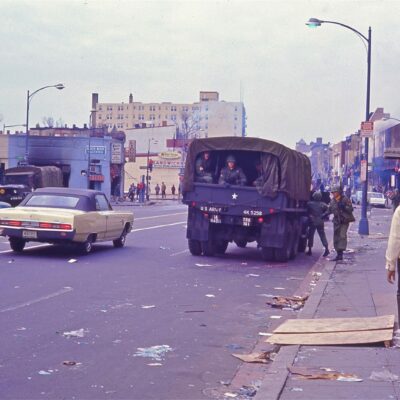

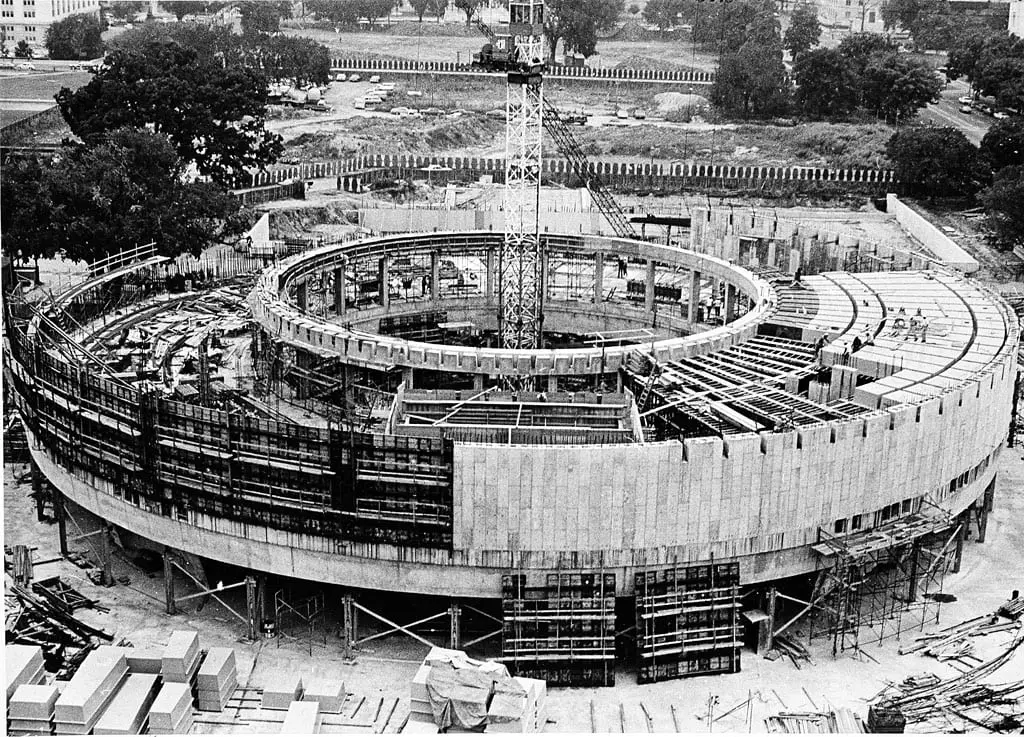

“Old Red Brick” was dismantled from 1968 to 1969 as the Smithsonian finalized plans for the new Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. The naming of a Mall museum for a living person was a bit controversial.

Round mound of rebound

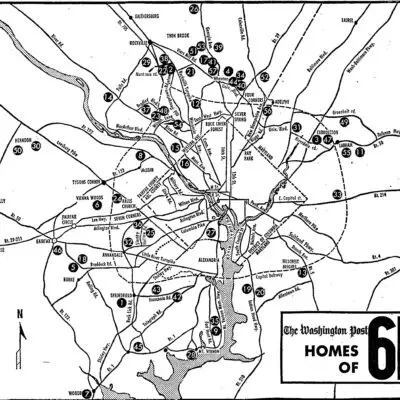

Washington wasn’t the only town courting Hirshhorn’s art. The Smithsonian’s secretary in 1966, S. Dillon Ripley, told Congress that the collector spurned serious offers from London, Jerusalem, New York, Baltimore, Beverly Hills, and Zurich. (Ripley also has an eponymous building on the Mall). Other locales offered to erect a museum for Hirshhorn’s collection – but none could compete with the prominence of the D.C. spot. The Mall won out. And Joseph Hirshhorn personally chose the architect: Gordon Bunshaft of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Bunshaft was a modern art collector himself – and he sat on the Districts’s Fine Arts Commission.

The 1970s must have been a banner time for the District’s concrete pouring industry. Our town is the unfortunate home to some of the angular icons of Brutalist architecture. A few federal cubes had already been completed on the opposite side of Independence Avenue. But the Hirshhorn is one concrete block that stands out. Its roundness is hard to ignore. Bunshaft would have preferred another material, but the outer walls of the museum are indeed poured concrete – as a result of budget cuts.

The opening of the Hirshhorn Museum was not without hiccups. The designer of the inaugural exhibition died before his work was complete. There was a construction bribery scandal. A few paintings were even stolen from the Hirshhorn estate in Connecticut (and later recovered). The building and its gardens were taking shape and taking some flak.

Hated it

Architecture critics and others had a field day when the museum opened in October 1974. Here are some of the most negative reviews (emphasis added):

“The largest doughnut in the world” -Ada Louise Huxtable, New York Times, 12/7/1973

“[Bunshaft’s] concrete cylinder strikes me all at once as a splendid setting for the Hirshhorn profusion and an abhorrent Fuehrer Bunker, as original and a cliche, as a marvel or engineered convenience devoid of endearing human qualities… Which leaves us with a building you cannot help but admire. You will hardly love it.” -Wolf Von Eckardt, The Washington Post, 9/28/1974

“The building’s bunkerlike appearance – it has no exterior windows except for a strip opening off a third-floor gallery – has been the subject of much criticism already. Washingtonians, who have been bickering about the building since construction started in 1969, are fond of calling the window the gun turret. That is not a particularly friendly comment — but then, this is not a particularly friendly building. From the street, in fact, it reads only as a gesture of urbanistic arrogance. The round windowless form clashes with buildings nearby…” -Paul Goldberger, New York Times, 10/2/1974

-ad 607-“The capital is less fortunate in the museum’s architecture than its art, however. It is regrettable that the new structure is one more stillborn monument on the Mall. Doubts that were raised about putting a sculpture garden on the uninterrupted greensward have not been allayed by the unrelentingly concreted setting. The sculpture would have graced the site more eloquently with no architectural design at all.” -Editorial Page, New York Times, 10/5/1974

“…the useless, ugly slit-like window and balcony area facing the mall appears as menacing from the outside as it is gracious in its interior.” -Henry J. Seldis, Los Angeles Times, 10/6/1974

“Already famous, or notorious, for its circular shape and windowless bulk and labeled a marble doughnut by by preconstruction publicity (high costs have substituted concrete aggregate for marble), it is known around Washington as the bunker or gas tank, lacking only gun emplacements or an Exxon sign. Its blind mass is broken by a Mussolini-style balcony on the Mall side. But jokes are too easy a dismissal of the undismissable. There are serious reasons why the museum and sculpture garden fail as architecture…” -Huxtable, New York Times, 10/6/1974

“…massive circular concrete building, like an illuminated babka…” -Harold Rosenberg, The New Yorker, 11/4/1974

“The space station comparison is apt because the building is so modern, so ‘sci-fi’ in its aspect, that it does produce an alienating effect. Also there is a rigidity and monotony in the circular construction, which compels the visitor to proceed in one direction through an unrelenting passageway of cold pink granite. While the design does have the advantage of encouraging orderly and rapid flow of traffic, its psychological effect is oppressive.” -Diana Loercher, The Christian Science Monitor, 8/22/1975

Familiar ring

Love it or hate it from the outside, the Hirshhorn building is a great space to view art. Most of the early reviewers fairly pointed out that fact in the museum’s first days. Nearly 40 years into the Hirshhorn’s existence, it’s impressive that the building can still hold its own among the District’s most edgy architecture. Not bad for not having edges at all.

Fun fact

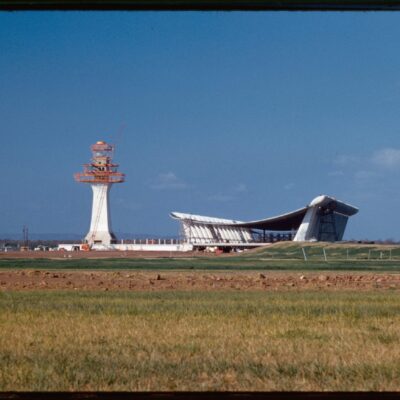

The Hirshhorn wasn’t the first modernist Smithsonian art museum planned for the Mall. In 1939, Eero Saarinen and his father Eliel won a competition to design a Gallery of Art that never materialized – partly due to the outbreak of World War II. The younger Saarinen went on to design some iconic modernist furniture along with the St. Louis Gateway Arch and the Dulles Airport.

About this post

Tom is out of town for a few days – so he asked some pals to fill in at GoDC. Aaron wrote this post. He’s a frequent Hirshhorn visitor and he plans to catch “SONG 1” on opening night. Look for a review in the comments. Aaron loves the building. He also wanted to note that his favorite items in the museum’s collection are the de Kooning women – painted on wooden doors. Totally perfect. If you’re reading this post and you happen to work at the Hirshhorn, contact Aaron if you have a key to the balcony and a few minutes for a tour. He’d be very grateful.