It’s probably obvious to GoDCers where Chain Bridge Road gets its name. There is a bridge that connects the eponymous road on the D.C. side to the one on the Virginia side.

But, this bridge has no chains. What’s the deal?

The bridge plays a significant part in Washington’s history, and as we were digging through the archives for some history, we came across the perfect old article to share: “Where Washington’s Historic Chain Bridge Gets Its Name,” published on November 21st, 1909 in the Washington Post.

This is a great one for our “Why Is It Named?” category.

The first question that is generally asked by persons on arriving at the Chain bridge for the first time is, “Where are the chains?” There are no chains, and there have been none for the last half century of more. But there were chains at one time that particularly designated the bridge that crosses the Potomac River at the Little Falls, several miles above Georgetown. The chains, too, were the all-important part of the bridge, for it was borne entirely by chains.

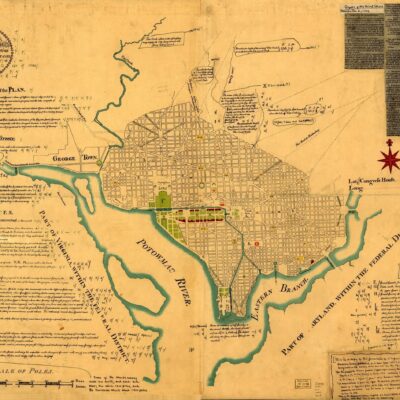

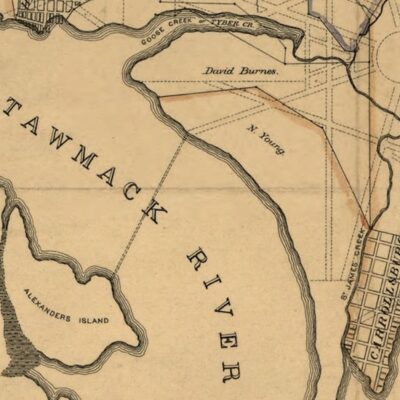

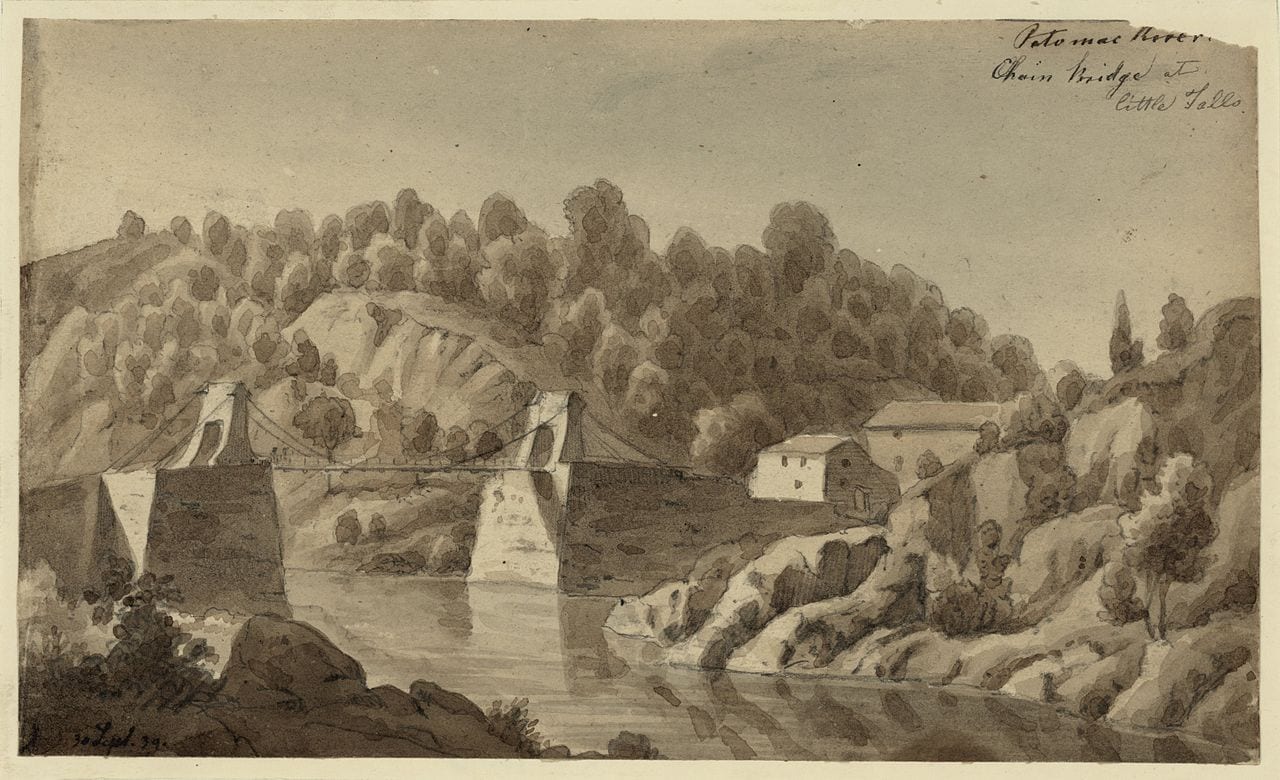

-ad 197-The first bridge over the Potomac at Little Falls, the head of navigation of the river, was built in 1809, just 100 years ago. It was built by a Mr. Palmer, and lasted only a short time, when it fell to pieces during a violent spring freshet. A second bridge took its place, but that only lasted even a shorter time, about six months. What was known as the Chain bridge was erected in 1810. It was a suspension bridge, supported entirely by chains thrown over the piers erected upon the abutments, which were about 20 feet high. These chains were four in number. the pendents were hung on them alternatively about 5 feet apart, so that each chain received a pendent in every 10 feet. The bridge was invented by Judge Findley, who lived near Uniontown, Pa., and where he had erected a similar chain bridge, which performed very good service for many years. the span of the bridge was 128 1-2 feet and the width 16 feet. Its weight was about 22 tons, which was regarded as a heavy weight in the bridge line in those days.

The bridge was built by the Georgetown-Potomac Bridge Company, the principal stock being owned by Virginians, through considerable of it was owned in Georgetown. It performed nearly all the service that was needed of it until 1852 when it was partially destroyed by a freshet. It was seriously damaged during a storm in 1840. In 1833 the corporation of Georgetown purchased the bridge from its owners by authority of an act of Congress, and by the provisions of the purchase it was made a free bridge. Previous to 1833 there was a heavy toll charged for crossing the bridge by its owners, 25 cents being charged for each horse that passed over it. The toll was so heavy that public sentiment was solidly against it, and this brought about its purchase by the corporation of Georgetown, Georgetown being then and for many years afterward an independent city.

Highway robbery! 25 cents was a lot of money back then, and just to cross a bridge.

The article continues.

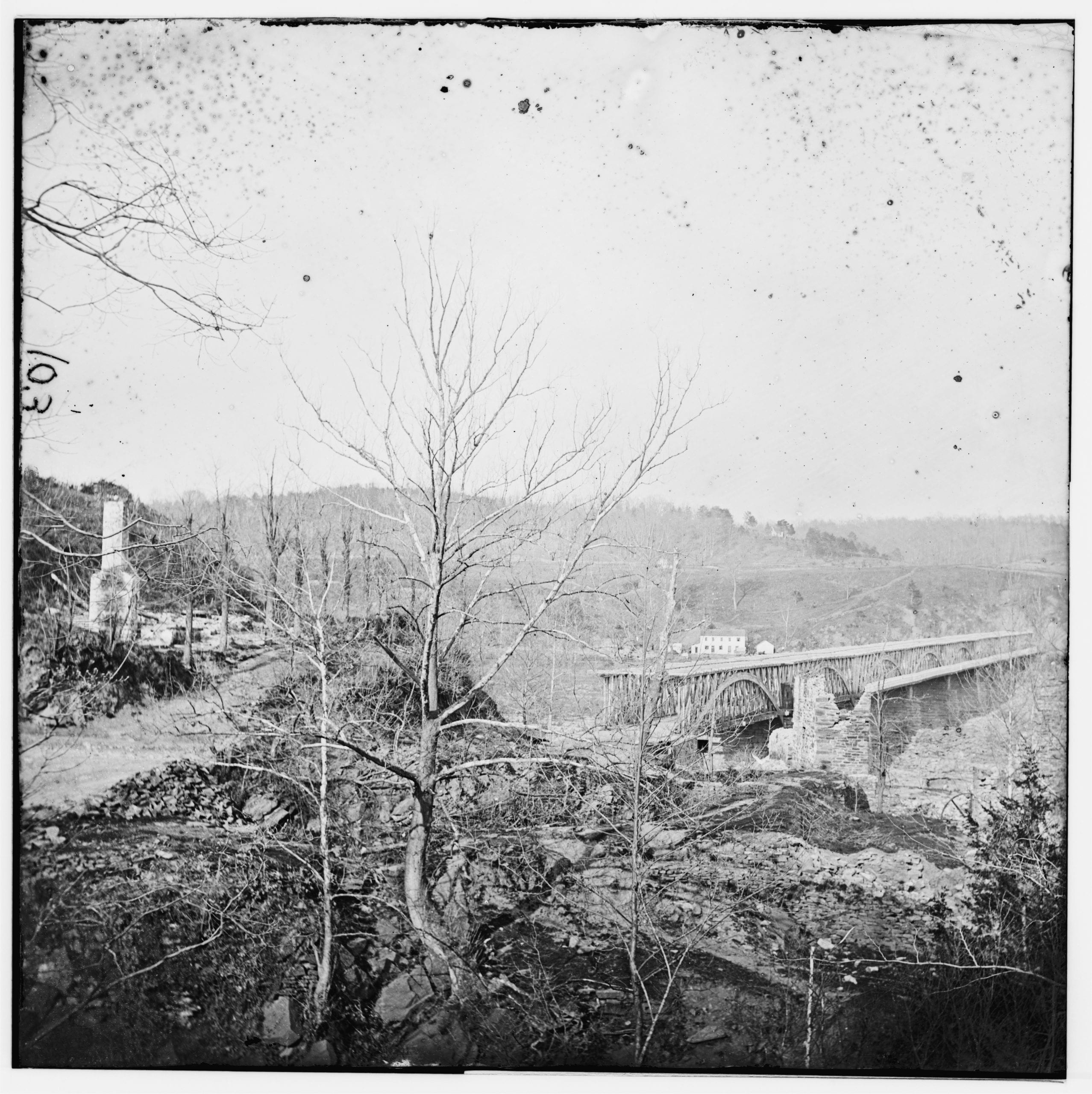

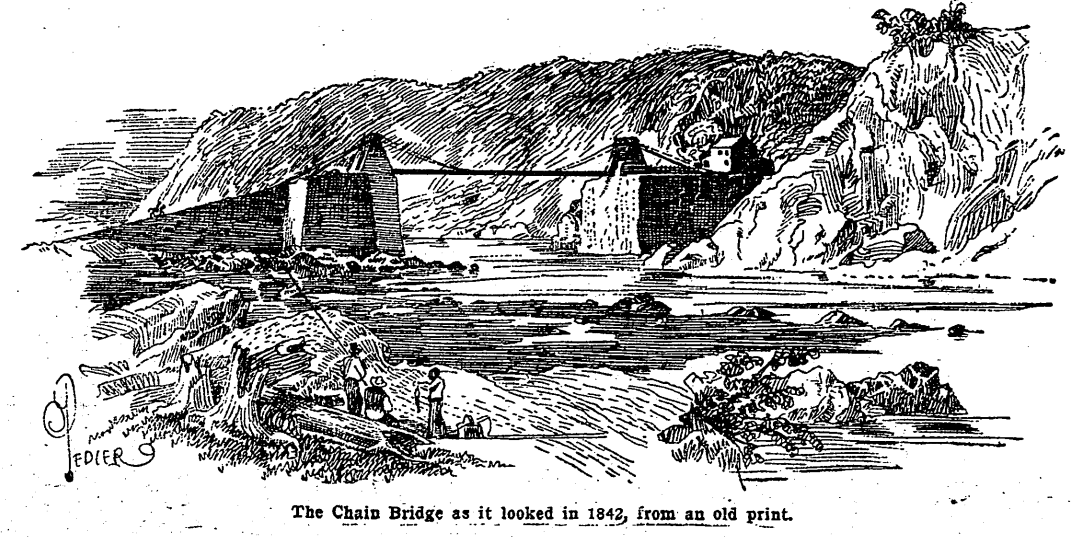

On March 3, 1853, Congress passed an act appropriating a sufficient sum of money to repair the bridge, and incidentally took the corporation of Georgetown out of the transaction, the United States stepping in as its owner, a transaction which was perfectly satisfactory to all concerned. This repaired bridge was still practically a chain bridge, though in the repairs iron in other forms was considerably used. The bridge covered only the river channel proper, there being a dirt roadway that approached the bridge from either side. It was the washing away of these approaches more than injury to the bridge itself that put the chain bridge out of commission so frequently, for it became almost an annual occurrence, particularly during the spring freshets, though in two or three years the washouts also occurred during the fall storms.

Strange as it may appear, there are no drawings or views of the bridge in possession of the War Department, and until today, in this issue of The Post, no authentic picture of the Chain bridge has ever been printed in a newspaper. This picture was secured from A. H. Ragan, the vice president of the Oldest Inhabitants’ Association, who found it in Morrison’s handbook of Washington, published in 1840, a copy of which is in the archives of the association.

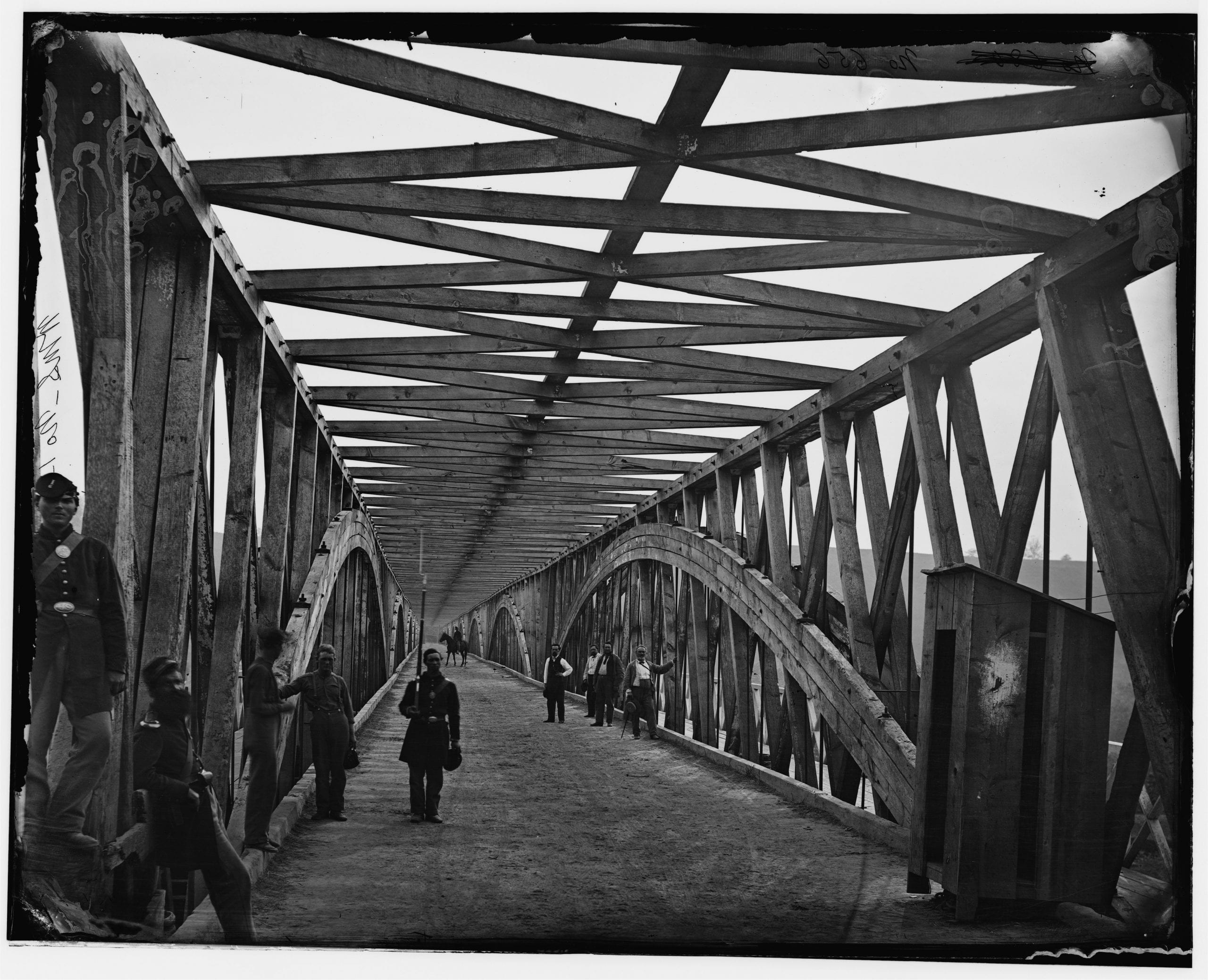

-ad 199-The Chain bridge, besides being famous for its chains and equally famous because it has no chains, played a very important part during the civil war [sic]. At one time one end of it was in possession of the Confederates, while the other end was guarded by Union troops. The particular command being volunteers of the District militia. The opposing forces were in talking distance of each other, a condition of things which, in the ordinary course of happenings, could not last long. In this case, however, it lasted for a couple of days, there being no orders issued for an advance from either side. In fact neither side was ready. Wars, like everything else, do not make much progress until there has been organization. Organization being secured, orders follow, the fun begins, and separations, victories, and defeats ensue. In this case the War Department was not ready on either side, and nothing serious to either side happened. When orders did come, and the District soldiery advanced to the other side, it was ascertained that the Confederates had left for Alexandria. There was, therefore, no battle of the Chain bridge for historians to write of, but there was all the anxiety and nervousness on both sides that usually precedes a battle.

It’s fascinating to think of the soldiers on either side of the bridge, on opposing sides of the war, being within shouting distance of each other. One wonders what conversations, taunts or intimidations took place. It reminds us of the Christmas truce in the trenches of World War I back in 1914.

And imagine if there had been a battle of the Chain Bridge. Then imagine that the Confederates were able to defeat the Union troops stationed there. It’s a quick march down the river to Georgetown and on to Washington.

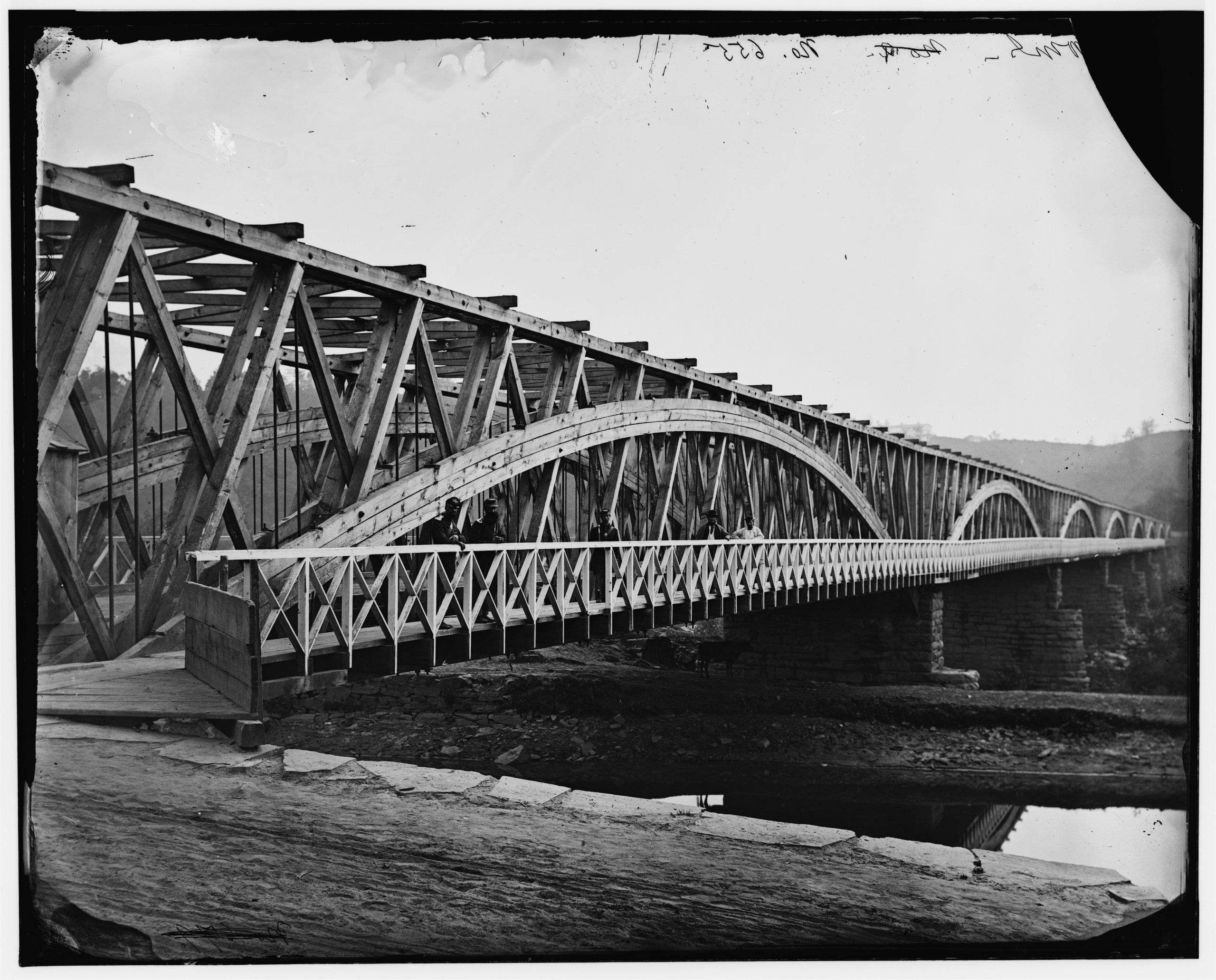

Take a look at the Civil War era photographs we dug up at the Library of Congress. Click on them for some amazing detail in a much larger version.

In 1872, Congress appropriated $100,000 for a permanent replacement made of iron. Construction on the bridge lasted until 1874, when it was rechristened “Chain Bridge” though no more chains were involved. The bridge also received significant damage by floods over the years, eventually leading to traffic restrictions in the 1920s due to safety requirements.

The floods of 1936 damaged the bridge to the point that it had to be shut down completely. In 1939, a new bridge was built on top of the old 1870s supports. This is the bridge that stands to this day … with no chains on Chain Bridge.